Belief in the afterlife played an important role in ancient Egyptian culture. While beliefs changed over the course of Egypt’s long history, and there were regional differences, general beliefs about life after death remained consistent. The afterlife was linked with the myth of the death of the god Osiris and the creation of the Duat as his new dwelling place. Initially, only royalty could be reborn in the afterlife, but access was soon democratized to anyone who could afford a basic tomb and appropriate funeral rites. Despite significant surviving evidence, Egyptian afterlife beliefs and rituals are still an enticing mystery.

Osiris and the Duat

It is a common misconception that the ancient Egyptians were obsessed with death. This is largely due to the copious number of tombs, grave goods, and texts relating to funerary practices that have been found. But in truth, the Egyptians were obsessed with life and wanted it to last eternally. Egyptian funerary rituals allowed life to continue after death in the “Field of Reeds.”

The ancient Egyptians believed that the afterlife looked a lot like life. People would work the land, live in the same home, have the same possessions, and meet with those who had already passed away, all without the dangers associated with life in the living world.

The idea of life after death is tied to the Osiris myth. In this narrative, Osiris, king of the gods, was killed and dismembered by his jealous brother Seth. The goddesses Isis and Nephthys reassembled the pieces of Osiris, except for his penis which had been eaten by a fish in the Nile. Nevertheless, Isis was able to become pregnant by the reanimated Osiris, and would later give birth to Horus, who would avenge his father and become the new divine ruler of Egypt.

But Osiris could not fully return to the world of the living, so the Duat, the Egyptian underworld, was created for him. Funerary rituals imitate the rituals undertaken to revive Osiris to allow the deceased to join him in the afterlife.

Deities of Death

While Osiris was the most important death deity in ancient Egypt, other gods were also significant within the sphere of death and funerary practices. Isis and her sister Nephthys were influential as mourners. Women were paid to imitate their sorrow for Osiris during funeral processions.

Anubis was the first deity to meet the soul of the deceased. His job was to guide the soul into the Duat. Anubis’ daughter, Qebhet, comforted the deceased while they waited in line for their final judgment.

Thoth was present at the final judgment and played an important part in the Osiris myth. He helped Isis hide Horus as a child and healed the eye of Horus when it was damaged by Seth in battle. Moreover, Thoth was the god of writing and language. He communicated the decision of the judges of the weighing of the heart ceremony.

The goddess Ma’at, whose feather is weighed against the heart of the deceased, encompassed the notions of harmony, justice, and truth.

For the deceased to join the gods in the afterlife, the physical body had to be properly attended to. The soul of the deceased was the only part of them that would proceed to the next life, but different elements of it would need to travel back to its tomb to receive offerings. This is why the Egyptians embalmed the dead, so that the soul would have a vessel to return to, resulting in the iconic image of the mummy.

Specific funerary rituals, such as the opening of the mouth ceremony, during which a magical tool was touched to the mouth and eyes of the deceased to re-enable them to breathe, see, and take in food and drink, were critical for allowing the deceased to prepare for entry into the afterlife. After the funeral and relevant rituals, the soul would rise and leave the body behind.

Elements of the Soul

In different writings, the soul was said to comprise five, seven, or (usually) nine elements, reflecting the multifaceted ancient Egyptian view of the essence of life. Each element played a different role in life, and in the afterlife.

The Khat was the physical body that had to be preserved to maintain a connection between the deceased’s earthly residence and the afterlife. The food and drink offerings left in the tomb by the living were thought to be taken in by the body; not in a physical sense but in a magical one. This would sustain the deceased’s soul.

The Sahu was the supernatural representation of the physical body which allowed the deceased to interact with the living world. The Sahu could appear in dreams or seek revenge if the deceased was wronged during their lifetime.

The Ren was an individual’s name, which was a significant part in a person’s uniqueness. Words were believed to have enormous power by the ancient Egyptians, and a written name could capture a person’s existence. One only needs to look at examples of pharaonic iconoclasm to understand the seriousness of erasing someone’s name.

The Ka is most akin to what we consider a person’s soul today. The individual is officially deceased when the Ka leaves the body, and it encompasses the supernatural energy that every living thing possesses. Furthermore, it was the Ka that needed to sustain and absorb the offerings through the Khat to remain existent.

However, the Ba is incredibly similar to the Ka and is often translated as soul in modern sources. It constitutes an individual’s distinctive personality. The Ba manifests in the iconic image of a bird with a human head, marking its position between life and the afterlife. It frequently journeys between the two. Interestingly, the plural of Ba, Baw, translates to “reputation” or “power.”

The Sechem is a more mysterious aspect and most scholars conclude that it represents the life force of a person.

The Akh was the combination of the Ka and Ba and is typically described as the “spirit” today. This stems from a line in the Pyramid Texts, known as Spell 474, which states that the corpse belongs to earth whereas the Akh belongs to the afterlife. The Akh was associated with intellect and mental capacity. This part of the soul also came back in dreams or as a ghost in the form of the Sahu.

An individual’s shadow or Shuyet was also an integral part of the soul. Since your shadow was always with you in life, the Egyptians believed it was a part of the person. Moreover, the Book of the Dead clearly states the shadow possesses protective elements, likely as some sort of guardian spirit.

Finally, the heart, known as the Ab, was the intrinsic essence of a person’s disposition. It was the key to their entry into the afterlife through the weighing of the heart ceremony. It was the spiritual manifestation of the heart (Hat in its physical form) and kept an account of the individual’s deeds when they were alive.

Configuration of the Duat

Upon death, a person’s body was embalmed to preserve the Khat. The Ka and Ba needed to recognize the Khat to become the Akh and proceed to the underworld, called the Duat. Once the opening of the mouth ceremony was performed, the tomb was sealed, and the mourners began feasting, Anubis was said to appear to lead the deceased into the afterlife.

Modern interpretations of the Duat largely derive from funerary texts dating to the New Kingdom (c. 1570-1069 BCE), for instance, the Amduat, a text first found in the tomb of Thutmosis I (c. 1506-1493 BCE). It describes the Duat as a parallel world that is entered before life, after death, and when people sleep. It suggests that the underworld is almost a parallel universe to the domain of the living. The Amduat maps the Duat according to Ra’s daily nocturnal journey across the dark side of the sky from dusk to dawn.

Another New Kingdom funerary text, the Book of Gates, details the existence of multiple magical creatures and landscapes in the Duat. These include lakes of fire, a hawk-headed lion, and the demon Apophis (who Ra vanquishes each night). It also provided space for the residences of all the famous deities.

The Book of Gates is a later addition to the mythology of the ancient Egyptian afterlife. It focuses on the twelve gates and their resident guardians that the soul of the deceased needs to travel through to reach the A’Aru, the Field of Reeds in the Duat, after the weighing of the heart ceremony. Alternatively, some traditions allow the soul to sail straight over the Lily Lake, if the deceased passed some sort of test of kindness posed by the magical ferryman.

The composition of the afterlife and the magical realm in which the dead resided was complicated and changed significantly from the Predynastic period to the Third Intermediate period, but the overall aim was to make it to the Field of Reeds, known as the A’Aru. There, a person’s life would be waiting for them including family members who had passed away, their possessions including furniture and books, and even old pets. In contrast, there would be no illness, no failed harvests, and an eternal spring season the deceased could enjoy with a pantheon of gods for neighbors.

The Final Judgement and Weighing of the Heart

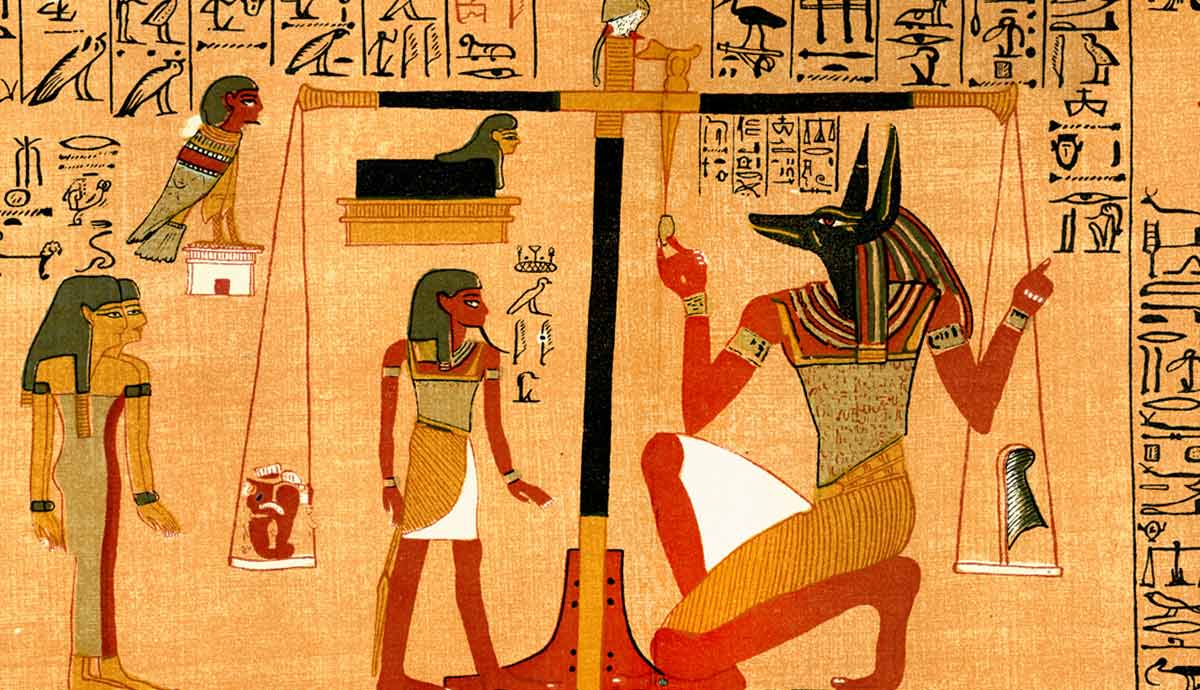

To reach the A’Aru, the deceased would have to successfully navigate the weighing of the heart ceremony. This is perhaps one of the most famous scenes depicted in ancient Egyptian art. Conducted in the Hall of Truth, the deceased must present their heart for judgment by Osiris, Ma’at, Thoth, Anubis, and 42 other judges. Once in the hall, the deceased would address the audience before reciting the Negative Confessions, a list of 42 sins they had not committed during their lifetime, with the aim of demonstrating their virtue.

Afterward, the heart would be weighed on the Scales of Justice against Ma’at’s white feather. Scarab amulets were frequently placed within the wrappings of mummies over the heart and inscribed with spells to ensure nothing would weigh down the heart. Likewise, spells within the Book of the Dead directly relate to this ceremony. For example, Spell 30B asks the heart not to betray its owner. This was the most important part of the journey to the afterlife since only if the heart balanced with Ma’at’s feather was the deceased granted access to the Field of Reeds.

On the other hand, if the heart was heavier than the feather of Ma’at, it would be thrown to the ground and eaten by Ammut, a creature with the head of a crocodile, forequarters of a lion, and hind quarters of a hippopotamus. Ammut was composed of the three most ferocious animals known to the Egyptians, which reflects the magnitude of the punishment. If Ammut ate the heart, the deceased would no longer have a soul and experience a second death. There was no ancient Egyptian equivalent for hell because there was no fate worse than ceasing to exist.

The Book of the Dead

Many notable ancient Egyptian mythological and religious texts describe the afterlife. The most famous is the Book of the Dead, originating just before the New Kingdom. It can be found within multiple tombs belonging to royalty, the elite, and anyone else who could afford it.

The less wealthy possessed shorter written spells and amulets that aided them in preparing for life after death. The weighing of the heart ceremony and the journey to the Field of Reeds are common themes, but a full copy of the Book of the Dead could contain over a hundred spells. Indeed 192 spells are known to us from the Book of the Dead, although no one copy includes every incantation.

The official translation of the book’s title is the Book of Going Forth By Day, and despite many variations between each copy, most versions can be summarized as a guide through four parts of the afterlife. First, the deceased is admitted to the underworld by Anubis and regains their earthly senses, then the deceased is resurrected and joins Re at sunrise, the deceased travels across the sky before being judged in the weighing of the heart ceremony and, finally, if successful, the deceased enters the Field of Reeds.

The Book of the Dead is an amalgamation of long-standing cultural beliefs and builds on both the Coffin Texts and the Pyramid Texts. The Pyramid Texts are the oldest texts about mystical funerary writings, reserved only for royalty and dating as far back as 2400 BCE. The Coffin Texts originated around 300 years after the Pyramid Texts as an increasing number of wealthy elites were able to enter the afterlife. By the New Kingdom, the afterlife was open to anyone who could afford funeral rites and offerings. Moreover, access was made easier as the deceased had spells and magical items to lead them through.