The Geneva Conventions represent a series of treaties drawn up during the 20th century in the city of Geneva, Switzerland. They consist of four treaties and additional protocols that establish international law standards for the conduct of war. The first Convention was created by what is now the International Committee for the Red Cross and Red Crescent (ICRC). The Geneva convention usually refers to the 1949 agreements, which were negotiated after World War II. The Geneva Conventions came into effect on October 21, 1950. The Conventions established the basic rights of prisoners of war (civilians and military personnel), as well as mechanisms for protecting the wounded, sick, and civilians during wartime.

The History of Geneva Conventions

The Red Cross was a key player in the formation of the Geneva Conventions, whose founder, Henri Dunant, initiated international negotiations that resulted in adopting the first convention on the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field in 1864.

During the Battle of Solferino in 1859, the Swiss businessman Henry Dunant visited the injured soldiers. He was astounded by the dearth of resources, including staff, equipment, and medical care available to assist these soldiers. The horrors of war pushed him to work on the book A Memory of Solferino, published in 1862. In the book, Henry Dunant proposed two solutions to address the issue:

- Setting up permanent relief societies in different locations that would assist the army medical services during wartime;

- Establishing a legal framework that would bind conflicting parties to care for all those affected by the war.

These suggestions led to the establishment of the Red Cross in Geneva, Switzerland. To put Henry Dunant’s ideas into practice, the Geneva Public Welfare Society created a committee in February 1863 with five members, including Dunant as secretary. This committee would later become the International Committee of the Red Cross. In October 1863, at the first conference, it was decided that the first relief societies would be established, and the staff would wear an armlet with the red cross.

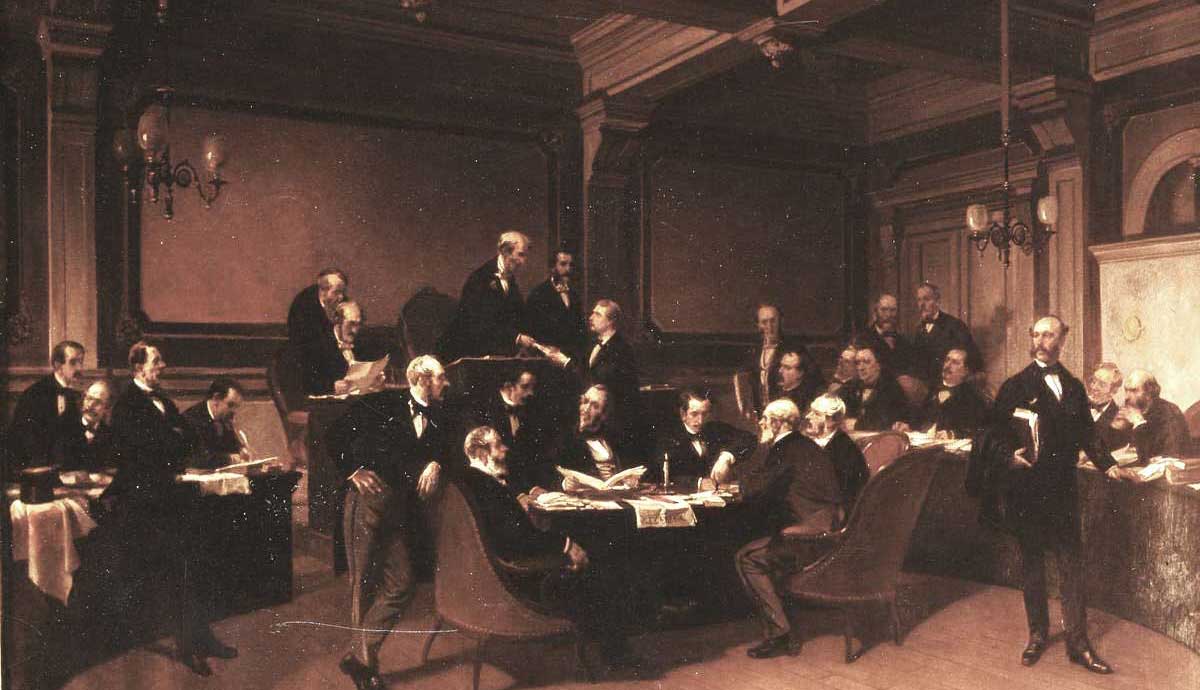

The Committee also persuaded the Swiss government to organize a diplomatic conference in August 1864. Delegates and military medical personnel from 16 countries attended it.

The conference led to the adoption of the first Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field, which was signed by 12 countries. The Convention provided the impartial treatment of all military, the protection of civilians assisting the wounded, and the immunity from capture or destruction of those societies providing treatment to the wounded and sick.

Despite Henry Dunant’s dedication to the development of the International Committee of the Red Cross, and the first Geneva Convention, which won him the first-ever Nobel Peace Prize in 1901, he lived and died in near poverty in 1910. Henry Dunant spent his final years in the Swiss village of Heiden, where he fell ill and was placed at a local hospice. He never made a full recovery.

The Geneva Conventions of 1906 & 1929

Soon after the first Geneva Convention, the need to revise the rules became apparent due to the ambiguities in the definitions of terms and concepts as well as the rapidly developing and changing nature of war and military technologies. Again, the International Conferences of the Red Cross Societies urged the Swiss government and the international community to elaborate on the amendments. As a result, additional Articles were adopted in 1868, along with the new convention of 1899, covering maritime warfare. In 1899, the Final Act of the Hague Peace Conference intended to limit or reduce armaments during wars and included a provision for planning another special conference to revise the first Geneva Convention. The Swiss government hosted this conference in 1906. Thirty-five states attended, aiming to improve the previous conventions.

As a result, the new Geneva Convention of 1906 replaced the older one, and its amendments included those wounded or captured during the war, also assigned volunteer societies and medical personnel of the Red Cross with new tasks, including treating, transporting, and removing the wounded or killed during the battles. The new convention was more precise and detailed in formulations, terminology, and juridical framework.

World War I clearly showed the deficiencies of the previous Geneva conventions and the Hague Convention regarding the civilized treatment of prisoners of war. To address the issue, in 1921, the International Red Cross Society suggested that an additional convention on the treatment of prisoners should be adopted. The organization provided the draft framework of the convention during the Diplomatic Conference organized at Geneva in 1929, which did not intend to replace the Hague regulations but to complement it. The new convention Relating to the Treatment of Prisoners of War stipulated that prisoners of war should be treated with compassion, be provided with the appropriate living conditions, and permit representatives of neutral states to visit detention camps. Following the widespread ratification of the 1949 Geneva Conventions, this convention is no longer in use.

The Geneva Conventions of 1949

Several conferences were held in 1948 and 1949 to reassert, extend, and modernize the previous Geneva and Hague Conventions. These conferences were driven by the wave of humanitarian and pacifistic passion that followed World War II and the revulsion over the war crimes exposed by the Nuremberg Trials. Even though Germany was the signing party of previous conventions, it did not prevent Adolf Hitler from committing atrocious acts during World War II, both on the battlefield and in civilian concentration camps. Hence, the need for the Geneva Conventions to cover non-combatant civilians became apparent.

In 1948, with the initiative of the International Red Cross, several conferences were organized to extend and modify the provisions. As a result, four distinct conventions were elaborated and approved in Geneva on August 12, 1949, which generally are referred to as The Geneva Conventions of 1949:

1) The Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field

2) The Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded, Sick, and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea

The first two conventions developed the principle that granted the sick and wounded neutral status.

3) The Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War convention further advanced the 1929 convention by enforcing humane treatment, proper nourishment, the distribution of relief supplies, and the prohibition of pressure on captives to provide more information than the required minimum.

4) The Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War. Even though the protection of civilians was already enforced by international law, the crimes of World War II showed the importance of reclaiming these principles. The convention prohibited the deportation of individuals or groups, hostage-taking, torture, collective punishment, offenses against “personal dignity,” imposition of judicial sentences (including executions), and discrimination based on race, religion, nationality, or political beliefs. In addition, the Convention mandated that militaries should protect civilians while achieving their stated goal of defeating the enemy, all without putting soldiers at additional risk.

Geneva Convention Protocols

Upgrading the Geneva Conventions and adopting new provisions in 1949 was not intended just to learn the lessons from World War II or to fill the gaps of the existing ones. It served the purpose of being more prepared for future conflicts, a reality that threatened the world in the wake of the US-Soviet Union confrontations and the new world order. Indeed, the numerous anti-colonial and insurrectionary wars in the decades that followed World War II posed a threat to the Geneva Conventions and illustrated the need for more detailed and codified conventions.

Conflicts and civil wars in Eastern and Central Europe or elsewhere (Yugoslavia, Rwanda, and Somalia, for example) blurred the distinction between international and internal conflicts, thus limiting the application of relevant rules of international law, including the Geneva Conventions.

To address the problem in 1977, two additional protocols were approved that covered combatants and civilians. Persons engaged in “self-determination” wars, which were now classified as international hostilities, were given protection under the Geneva and Hague conventions by the first protocol, known as Protocol I.

Additional Protocol II complements Article 3, also known as Common Article 3, which is maintained in all four Geneva Conventions and relates to the protection of victims of non-international armed conflicts. It forbids:

“Collective punishment, torture, the taking of hostages, acts of terrorism, slavery, and ages on the personal dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment, rape, enforced prostitution and any form of indecent assault.”

Protocol II also outlined specific regulations that intend to better safeguard those who are victims of internal armed conflicts within one nation’s boundaries. However, the scope of this protocol is more limited considering the respect for the principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of a sovereign state.

The 1949 conventions now include members from almost 180 states. The United States is not a party to either Protocol I or Protocol II, which both have more than 145 states as members. The authority of international fact-finding commissions to look into claims of grave violations or other major violations of the treaties or Protocol I have also been acknowledged by more than 50 nations in their declarations.

Many things have changed since the 1949 Geneva Conventions were adopted, including political environments, geopolitical alignments, and the accessibility of more lethal weapons. Yet, one thing remains the same: how a war is fought impacts the fate of many people, including civilians.

In 2009, to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the Conventions, Knut Dörmann, then the Head of the Legal Division of the International Committee of the Red Cross, gave the following speech at a joint conference of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the British Red Cross:

“The Geneva Conventions remain the cornerstone for the protection and respect of human dignity in armed conflict. They have helped to limit or prevent human suffering in past wars, and they remain relevant in contemporary armed conflicts.”