For various reasons, up until well after the Protestant Reformation, the Roman Catholic Church generally resisted the translation of the Bible into vernacular, or common, languages. However, the Catholic Church was unable to stem the tide for various reasons, particularly in the English-speaking world.

Why Didn’t Roman Catholics Translate the Bible into Common Languages?

The rationale for the Roman Catholic Church to resist a vernacular tends to lie on which side of the Catholic/Protestant divide a person takes. For the Catholic, it was practical – generally, the Roman Catholic Church holds that it is the proper translator and communicator of Biblical truth, and that such work should only be done within and through the Catholic Church. At the Council of Trent in 1546, it had declared that the Latin Vulgate produced by Jerome in the 400s CE was the authoritative text for the church.

For Protestants, the Catholic resistance was about control over theology and translation. The theology of sola scriptura – that the Bible alone was the authority of faith, not what the church said the Bible taught – meant that the individual believer needed access to and the ability to discern scripture on their own. Due to the theology of sola scriptura, what occurred leading up to, and as a result of, the Protestant Reformation beginning in 1517, was the production of various translations in common languages.

What Was the Wycliffe Bible?

Up until the invention of mechanical movable-type printing by Johannes Gutenberg in 1450, there were few Bibles produced in vernacular languages. Probably the most notable was the Wycliffe Bible, a project inspired by John Wycliffe and the Lollards to have a Bible for English-speaking people in the 1300s. They believed in a form of sola scriptura, and translated the Bible from the Latin Vulgate into English to promote their ideas.

What Was the Tyndale Bible?

The main development following Gutenberg, which led to the production of numerous vernacular Bibles, was the compilation of known Greek texts into a singular volume, printed by the scholar Desiderus Erasmus in 1516. What Erasmus accomplished allowed other scholars to translate the Bible into their own languages, not from the Latin Vulgate, but from the Greek and Hebrew texts which the Bible was originally compiled in the first century. It is important to note here that translation work – such as Jerome translating from Greek to Latin – involves a necessary amount of personal theological input in some word choices. When translating from Latin to English, the translator may not know what options Jerome may have had in his word choices.

However, when William Tyndale was able to utilize the Greek texts in the 1520s, he was able to work more closely with the original material, making choices that were controversial at times to the Roman Catholic Church, which held a theology closer to the Roman Catholic Church and medieval thought. He produced Bibles that were condemned by the head of the Church of England, King Henry VIII, who sought their destruction, but the momentum of vernacular translation was already in motion. Henry VIII even commissioned a Bible in response, the Great Bible of 1539.

What Was the Geneva Bible?

When Mary I ascended to the throne of England, she restored the Roman Catholic Church (Henry VIII had split away from it to form an independent Church of England during the English Reformation), and various Protestant scholars left for Geneva in the 1550s and began work on a new translation, the Geneva Bible, which reached England and Scotland in the 1570s. There it found wide acceptance, particularly in Scotland, which even required each household to own a copy by 1579.

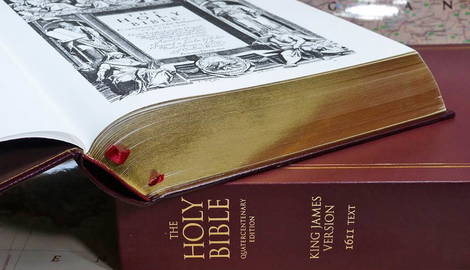

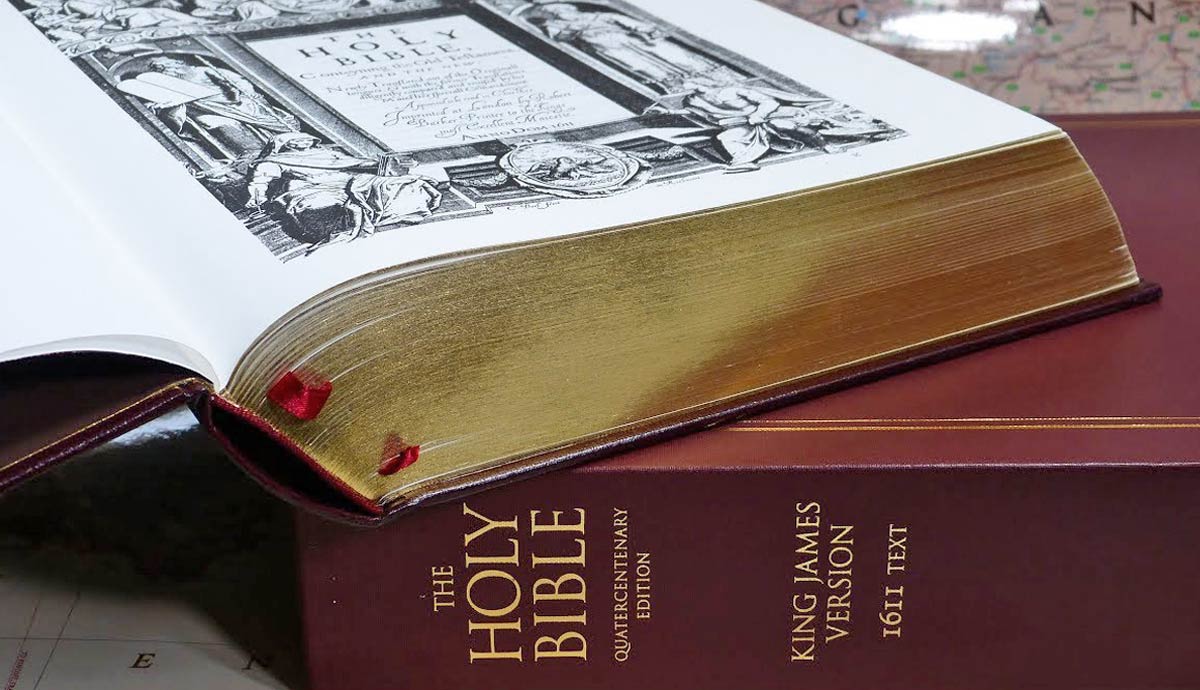

The Geneva Bible was heavily influenced by Calvinistic thought, being produced by Puritans. It borrowed heavily from Tyndale’s translation, and was generally opposed by the Roman Catholic and Church of England hierarchy. In response to the Geneva Bible, King James I commissioned what became known as the King James Bible in 1611, and the Roman Catholics produced the Rheims-Douai Bible beginning in the 1580s. The King James Version of the Bible would eventually become the standard Bible for English-speaking Protestants up until the 1900s. It still remains in use today among many congregations, and has been a heavy influence on English language since that time.