The so-called Mad Hatter is one of the most celebrated characters in Lewis Carroll’s much loved Victorian classic Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, 1865. While Carroll only ever referred to this character as ‘The Hatter’, he became widely known as ‘the Mad Hatter’ for his colorful and eccentric behavior, and the illustrations by so many artists that accompanied the numerous versions of the publication over the decades. Many have tried to decipher the symbolic meaning of the so-called Mad Hatter, and there are numerous interpretations, including those on our list below.

Victorian Hatters

Hatters were widespread in Victorian society, given how popular hats were across all strands of society during this time. However, many hat companies began using mercury while curing pelts in the hat making process without realizing how harmful it could be. When mercury worked its way into the systems of the hat makers, many of them suffered a series of physical and mental health conditions, including dementia, leading to the rise of the expression “Mad as a Hatter.” Carroll may have made reference to this phenomenon with his ‘Mad Hatter,’ who came to typify a particularly dark moment in the British fashion industry, even if his Hatter’s character traits were not typical of mercury poisoning.

A Caricature of Theophilus Carter

One theory that has been circulated since the book’s publication, is that Carroll in fact based his Hatter on a real person – an eccentric and well-known British furniture dealer named Theophilus Carter, who resided in Oxford at around the same time as Lewis Carroll. Carter was well-known by locals for standing in the door of his furniture shop chatting with passers by. He had a distinctive look that made him stand out, with a prominent nose and receding chin, while wearing a top hat on the back of his head.

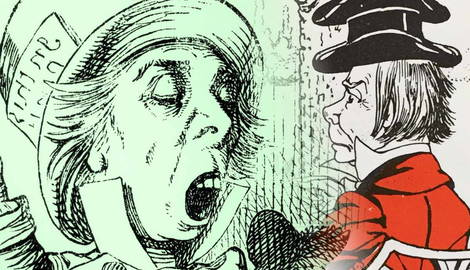

In fact, Carter was known in Oxford as “the Mad Hatter”, and H.W. Green argued in 1935 that Carroll had asked the book’s first illustrator, John Tenniel, to model his drawings of the Hatter on Carter – the resemblance, many have noted, was uncanny. Tenniel’s drawings are the most famous depiction of the Mad Hatter, and inspired following illustrations and film depictions to come.

Mental Health Disorders and Eccentricity

One of Carroll’s aims in writing Alice in Wonderland was to form a critique of Victorian society. It was a problematic time for mental health sufferers, who were treated with little dignity or respect. Some critics have argued that Carroll explores how we might approach the ‘mad’ or ‘insane’ with greater empathy and understanding, by painting his central unstable character as an eccentric, but ultimately harmless person.

It also seems likely that Carroll may be highlighting the nonsensical nature of life as an adult through the Mad Hatter’s eccentric and odd behavior, which is so often contradictory and unpredictable. Carroll seems to highlight how difficult this might be to find sense or meaning in for those on the brink of adulthood such as Alice.

An Unpleasant Aspect of Our Inner Nature

Of all the characters Alice encounters during her adventures in Wonderland, the Mad Hatter is one of the most maddening and confusing, offering Alice a series of unsolvable riddles and addressing her in a direct and often uncompromisingly rude manner. While this might be explained away by his supposed ‘madness’, some critics and readers believe Carroll made the Hatter this way in order to highlight some of the most irritating and unpleasant traits in our human nature, which, although not life-threatening, can still make life quite unbearable.

Contemporary illustrator Ralph Steadman interpreted the character in this way for his own recent illustrations, on which he wrote, “The Hatter represents the unpleasant sides of human nature. The unreasoned argument screams at you. The bully, the glib quiz game compere who rattles off endless reels of unanswerable riddles and asks you to come back next week and make a bloody fool of yourself again.”