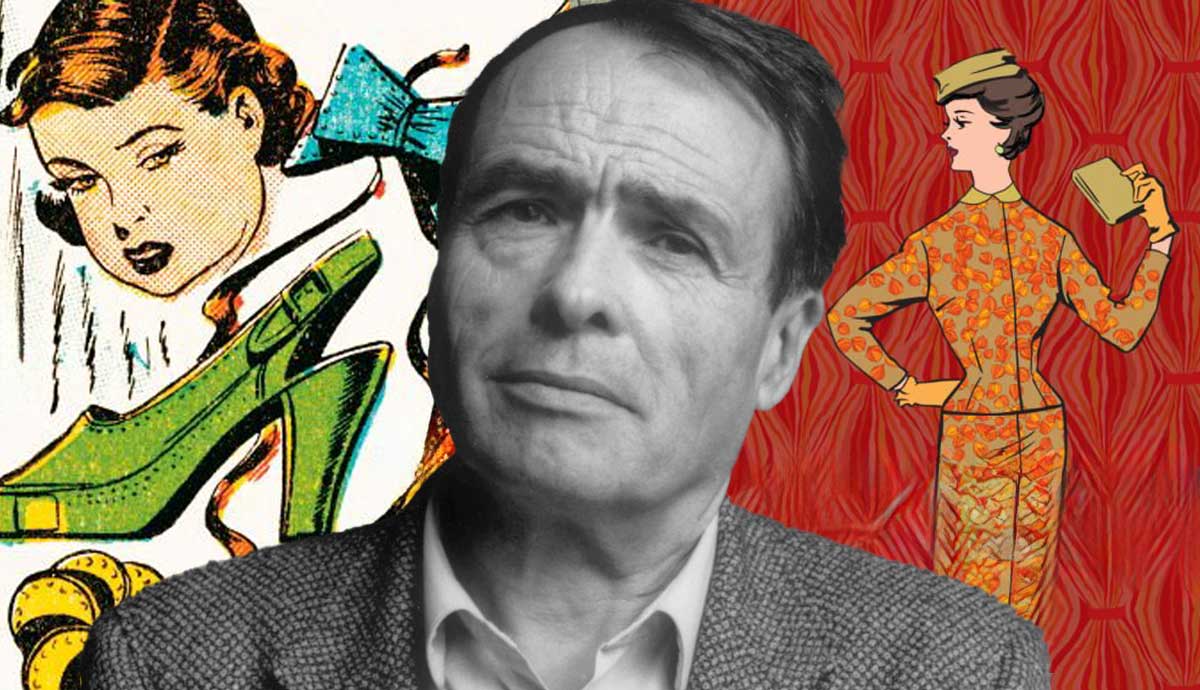

Pierre Bourdieu’s work delved into the notion that the reproduction of social elites requires a more complex, subtle explanation than merely wealth. Instead of focusing on the economics of capitalism, he wrote about cultural capital – education, intellect, style of speech, dress – that are valued within capitalist society. Bourdieu was a trailblazer to some and a heretic to others. The ‘difficulty in sociology,’ Bourdieu believed, ‘is to manage to think in a completely astonished and disconcerted way about things you thought you had always understood’. In Distinction: A Critical Judgement on Taste (1979), he claimed that contrary to popular belief, taste is not ‘personal’, but a reflection of social class and a means of strategy and competition.

What Is Taste?

For Immanuel Kant, beauty was not an inherent property of an object but an aesthetic judgment based on subjective feeling. Similarly, social taste is said to refer to the preferences and choices individuals make regarding social activities, fashion, food, music, and other various forms of consumption. Taste differentiates us from others and expresses our identity. It serves as a marker of consumption patterns and lifestyle choices.

Cultural taste also aligns with social class and subcultural groups. For instance, upper-class taste might include an appreciation of fine art, fine dining, and classical music, while Goths might favor black clothing, horror films, and bands like The Cure. Stereotypical young urban professionals appreciate slick digital devices, designer glasses, trendy cafes, and artisanal coffee.

Individuals and groups critique the “bad taste” of some and admire the “good taste” of others. Bourdieu’s genius was to show that taste is less personal and subjective than it appears.

Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste

The crux of Bourdieu’s argument in Distinction: A Critical Judgement on Taste (1979) is that taste is a shared social activity. So-called ‘superior’ taste, be it in food, art, music, or style – legitimate culture – isn’t a matter of the inherent superiority of certain individuals, but follows a distinct social logic.

Bourdieu’s trick is to reject the traditional idea that taste is somehow innate and subjective. Instead, he sees it as reflective of the social hierarchy that structures society. Individual cultural needs, for example, attending concerts or museums, or preferring certain music, art, or interior design styles, are closely linked to education level and social origins.

Distinction shows that taste – the cultural preferences we have – strongly correlates with key indicators of social class. The implication is that a person’s social class not only predicts but also determines their cultural and social preferences. Consequently, taste in culture is not a ‘gift of nature’ but a ‘product of upbringing and education.’

Distinction Through Social Taste

According to Bourdieu (1979): ‘social subjects, classified by their classifications, distinguish themselves by the distinctions they make, between the beautiful and the ugly, the distinguished and the vulgar, in which their position in the objective classifications is expressed or betrayed.’

In other words, social classes define their preferences, based upon the creation of identity and separation from other groups. Social groups – dominant or otherwise – distinguish taste in specific ways and what is valued in one context may not be in another. For instance, jazz may be esteemed in one social circle, while Norwegian black metal may be highly regarded in another.

Taste is therefore not individual but deeply social. Expressing similar cultural tastes to others within a given social class is not individualism at all but simply confirming social norms. Our choices, whether deemed beautiful or ugly, are influenced by the class of which we are part and portray our position within the social hierarchy of society.

Taste As A Social Weapon

Cultural taste, then, doesn’t freely float through society but structures it through distinction, as substantial barriers between social groups are reproduced. Those with high levels of what Bourdieu calls “cultural capital” – social assets such as education, intellect, style of speech, and dress – set the norms of “good taste” within society.

Conversely, those with low cultural capital accept the ruling class’s definition of taste as natural and legitimate, as high culture is distinguished as ‘superior’ to low culture. Taste is effectively weaponized, allowing the dominant classes to dictate what is good and bad taste for the middle and working classes.

Good taste aligns with the preferences of the dominant classes in the same regard, as Karl Marx wrote that “the ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas.” Bourdieu’s theory of taste helps to make sense of the relationships between social hierarchies and cultural practices. Additionally, it illustrates how social structures become embodied through the tastes and practices of individuals within a society.