Futurism as an art movement poses questions on the legacy of the past and the future of culture. Emerging in Italy among right-wing radicals, it soon found new life in the Russian Empire, among the ideologically opposite anarchists and communists. Russian Futurism rejected the academic tastes of the elites and emphasized its folk roots. Read on to learn more about the nuances of Russian Futurism.

Italian Futurism: Roots and Aspirations

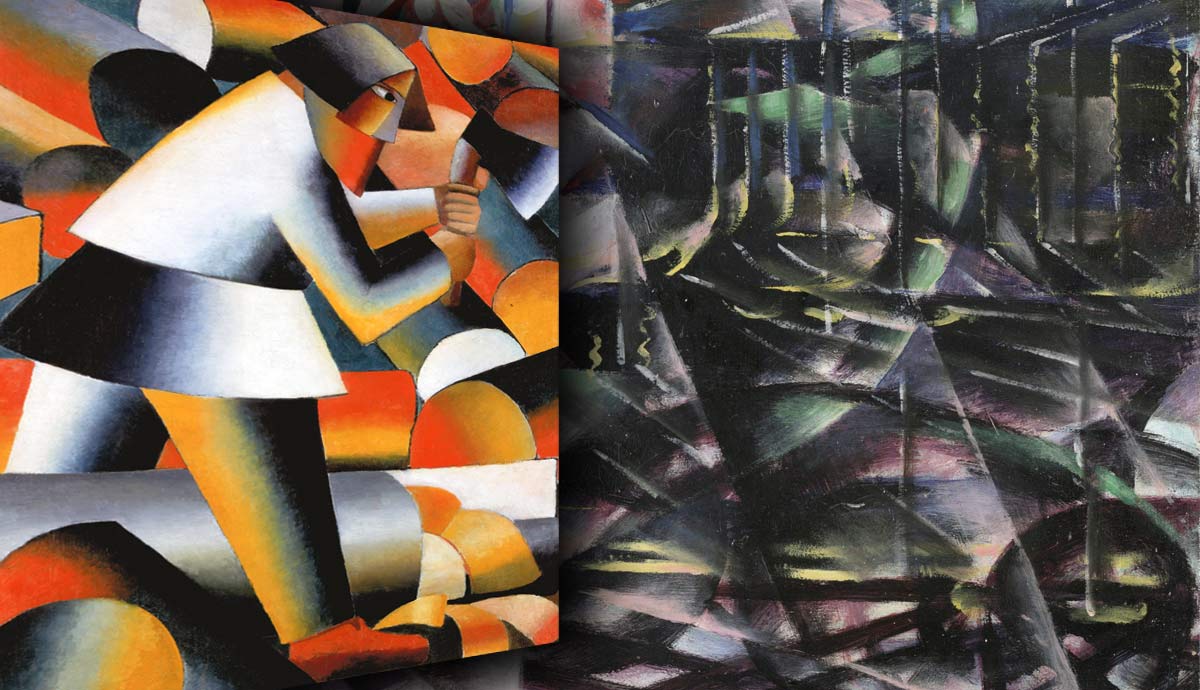

The art movement of Futurism was a significant invention and the product of the early twentieth century. Young Italian artists detested the fact that their country was associated mostly with ruins and sculptures of antiquity, and aimed to design a brighter future. In its expressive language, Futurism was a child of Impressionism, with its sharp focus on light and urban settings, as well as Cubism which presented a multi-planed vision of objects. However, the Impressionists were too fixated on society and its conditions and Cubists could never overcome the immobile rigidity of their geometric compositions. Italian Futurist painting was dynamic, bold, and focused on technological progress, speed, and functional properties of mechanisms. In 1909, Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti published a manifesto, proclaiming Futurists’ hatred for everything old and devotion to progress, violence, and reinvention of Italian culture.

Russian Futurism: Reinventing the Concept

Meanwhile, The artists and poets who created the movement have never seen the works of Italian Futurists. It is likely that they have read Marinetti’s manifesto, or at least were familiar with its content, but the works of Balla, Boccioni, and other Futurist legends never reached the borders of the Russian Empire. The word Futurism used by Eastern European artists was thus very nominal and used as an umbrella term for the revolutionary avant-garde.

Within the movement, no one had a coherent idea of the visual qualities of Futurist art. While the Italians denounced all the legacy of the past, the Russians embraced it, seeing expressive potential in folk art and traditional decorative patterns. Their rejection of the past related to the academic standards of art and poetry, and the so-called ‘good taste,’ with folk art standing in inherent opposition to it. Some resorted to neoprimitivist techniques, while others invented their own theories of art.

Artistic couple Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov created a short-lived art theory of Rayonism. In an elaborate, yet not entirely coherent manifesto, both artists insisted that the human eye perceived the world not through the images of objects, but through rays of light reflected by them. Painting these rays was meant to reach the essence of human perception and remove the barriers confining art. Art historians think of Rayonism as a small yet significant step towards the spread of abstract art among Eastern European artists.

Poetry, Politics, and Provocation

In terms of their political affiliations, Russian Futurists were mostly left-wing or anarchist. They denounced the bourgeois taste in art and actively attacked everything popular and acceptable. Contrary to their Italian counterparts who preferred tailored suits and conventional appearances, Russian Futurists painted their faces with geometric figures, wore voluminous blouses of the wildest of colors adorned with flowers, and aimed to turn their entire existence into provocation.

The provocation took its shape in literature as well. In 1912, poets David Burliuk and Vladimir Mayakovsky published a manifesto A Slap in the Face of Public Taste that pronounced the rejection of all poetic tradition and established the poet’s right to enrich the language by introducing new words and sound combinations. Futurist poetry often prioritized acoustic expressivity over semantic content, writing poems entirely from palindromes, invented sounds, and exclamations.

The Demise of Russian Futurism

Most of the politically engaged Futurists welcomed the 1917 revolution, believing it was necessary to end the monarchist tyranny and the bloodshed of World War I and establish a new society of social equality and progressive culture. However, this illusion shattered rather soon. Some artists emigrated to Europe during the first years of the Soviet Union, while others enthusiastically started to build a new world. With them, Futurist ideas blended with Communist ideology, resulting in the invention of Constructivism. Artists aimed to revolutionize daily lives and aesthetic perception of Soviet people, introducing a new radical aesthetic with no inherent class differences or elitist over-intellectualism. Visual art became practically oriented, with artists moving to architecture or textile design.

However, it all came to an end by the late 1920s, when Soviet politics took a conservative turn with the rise of Joseph Stalin to power. Avant-garde art became too unpredictable and too liberating, and that posed a threat to the paranoid government seeking to grasp control over its citizens. Many artists and poets fell victim to the Great Terror of 1937, and some committed suicide, unable to live and work in the new world they had previously welcomed.