Suprematism was a profoundly influential art movement from the early 20th century, founded by Russian artist Kasimir Malevich. Today, art historians now recognize Suprematism as one of the first completely abstract art movements. But what does Suprematist art actually look like? Suprematism focused on geometric shapes such as circles, squares and crosses, painted in dark colors on a pale backdrop. Its artists believed these seemingly simple shapes held within them the pure, distilled essence of our human existence. Here’s our handy rundown of the most important facts about Suprematism, which Malevich described as the “supremacy of pure feeling or perception in the pictorial arts.”

1. Suprematism Collapsed Together Futurism and Cubism

No art movement exists in a vacuum, not even one as entirely abstract as Suprematism. Indeed, the simple forms of squares, crosses and circles that the Suprematists painted were part of a slow and gradual process of reduction. Many of the artists associated with Suprematism had previously made art in the jagged, geometric styles of Cubism and Futurism, before reducing their languages down to their most basic elements.

2. The First Exhibition on Suprematism Was in 1915

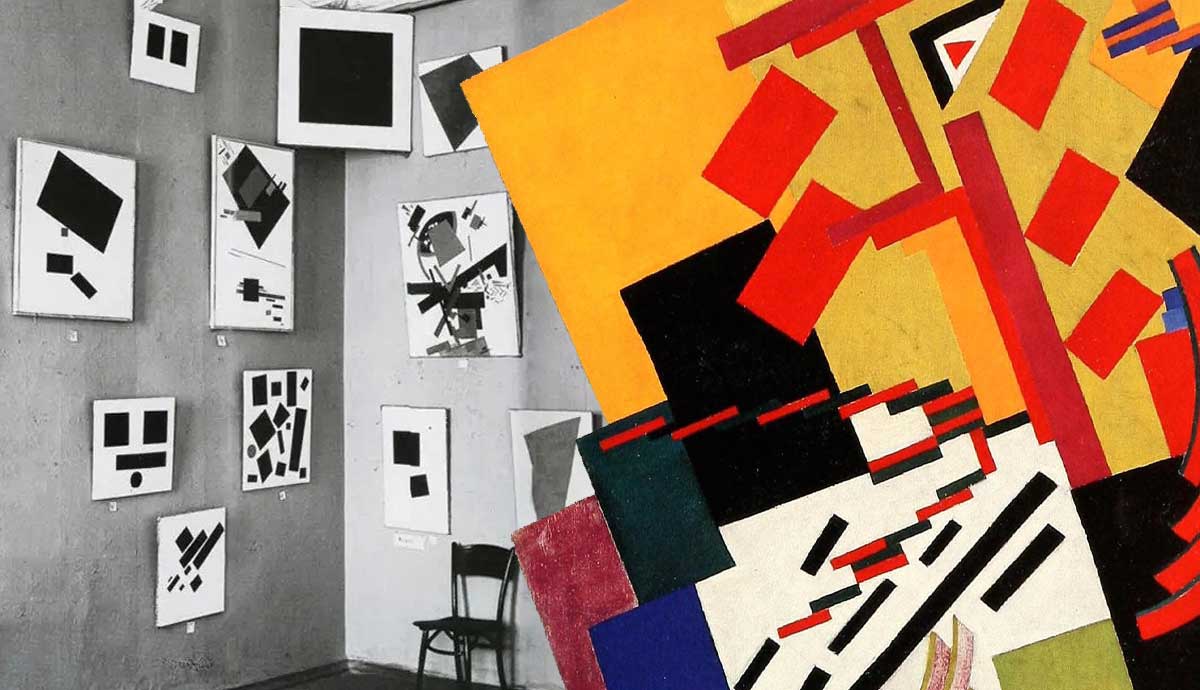

Kasimir Malevich was the first artist to begin experimenting with a version of Suprematism in around 1913. Later, the artists Kseniya Boguslavskaya, Ivan Klyun, Mikhail Menkov, Ivan Puni and Olga Rozanova joined him. Together, they formed the Suprematist group. They staged their first exhibition in Russia, titled The Last Futurist Exhibition of Painting 0.10. Together, the artists displayed a series of artworks featuring only geometric shapes against white or pale backgrounds.

Often artists made their squares, circles and rectangles angled to appear suspended mid-air, creating the sensation of weightlessness. Artists experimented with both stark monochrome compositions, and bold, striking passages of color, toying with which could create the most lively and dynamic visual impact. They hoped these stark, direct designs could convey the inner spiritualism of the human experience, reduced into its core, foundational elements.

3. Malevich Wrote the Movement’s Manifesto

As with many modern art movements, it was the stirring manifesto, written by Kasimir Malevich, that truly cemented Suprematism as a new style of art to be reckoned with. Malevich made a series of grand and lofty claims in his manifesto, arguing that he had crossed the threshold from the real world into a new, higher realm of non-objectivity.

He wrote, “Under Suprematism I understand the primacy of pure feeling in creative art. To the Suprematist, the visual phenomena of the objective world are, in themselves, meaningless; the significant thing is feeling, as such, quite apart from the environment in which it is called forth.”

4. The Painting Black Square, 1915, Defined Suprematism

If any one work of art came to encapsulate the Suprematist style, it would have to be Kasimir Malevich’s iconic painting Black Square, 1915, unveiled to the public during the first exhibition of Suprematism (see above). While we are now well used to seeing such abstract paintings today, it is important to note that when this artwork was made, no one had seen anything like it before, and taking the courage to paint something so stark, direct and simple was an act of true bravery that would have profound repercussions throughout the course of art history.

On creating this painting, Malevich wrote, “In the year 1913, trying desperately to free art from the dead weight of the real world, I took refuge in the form of the square.” Many art historians now cite Malevich’s radical Black Square as the first ever abstract work of art.

5. They Were Widely Criticized

Like many pioneering art movements, Suprematism fell victim to harsh criticism during its day. Many critics lambasted the artists, ignoring the spiritual connotations of their geometry and instead accusing them of making art that was nihilistic and meaningless. The artist and critic Alexandre Benois even called their art a “sermon of nothingness and destruction.”

Nonetheless, the movement proved popular amongst countless artists across Russia. Many found ways of integrating ideas around Suprematism into their art, as demonstrated in the subsequent Russian Constructivist movement. Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, the Stalinists condemned avant-garde art that didn’t adhere to the strict doctrines of Socialist Realism, and Suprematism and Constructivism gradually dissolved. However, various Russian artists who travelled to Europe were able to develop and share their ideas, including El Lissitzky and Naum Gabo.