Cubism was one of the most monumental art movements of the early 20th century. Some even say it was so radical, it marked the true beginning of modern art. Cubists broke apart the pictorial conventions of realism and perspective, replacing them with shattered forms and angular, geometric shards. It was a relatively short-lived movement that lasted from 1908 to around 1914, but in those six years a huge range of avant-garde artwork was made. To try and make sense of it all, art historians have divided Cubism into two distinct phases: Analytical Cubism (1908-1912), and Synthetic Cubism (1912-14). In this article we ask, what is Synthetic Cubism, and how can we recognize it?

Synthetic Cubism Is the Second Phase of Cubism

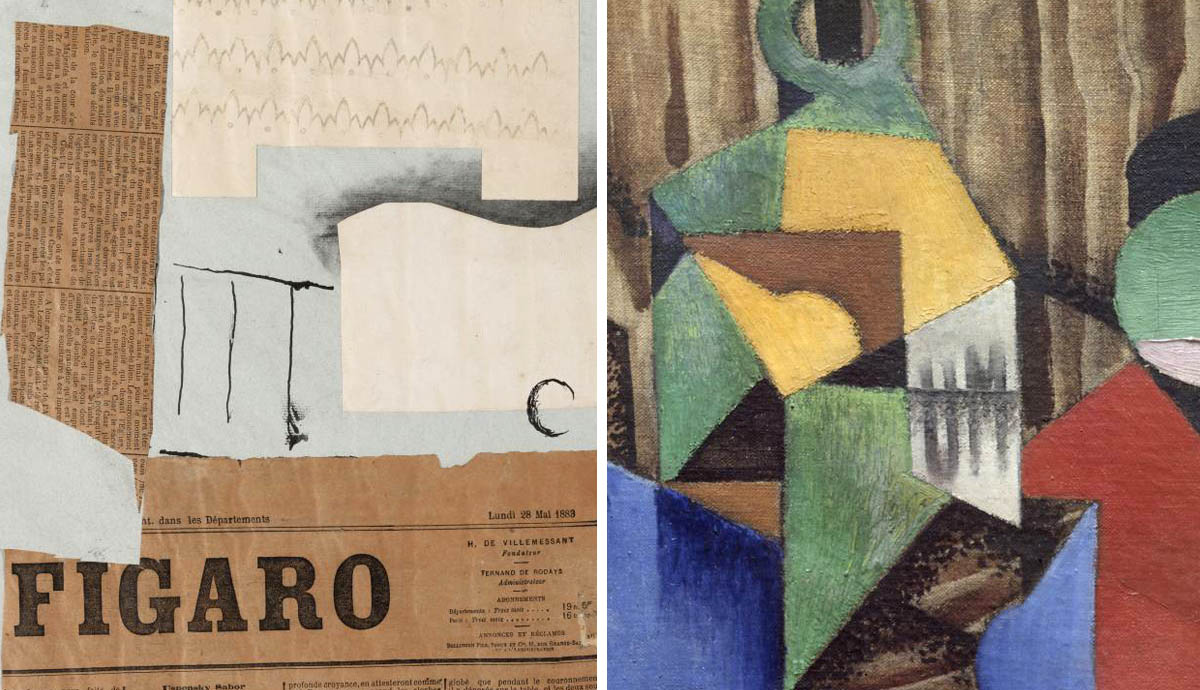

Synthetic Cubism is a term commonly used by art historians to describe the second phase of the Cubist movement, emerging during and after Analytical Cubism. The first phase of Cubism was generally defined by complex designs, multiple perspective, and muted color schemes. In contrast, by 1912 Cubist artists began incorporating elements of found materials and collage. The word ‘synthetic’ was a reference to the incorporation of man-made materials such as newspaper, patterned paper and other textured surfaces.

In fact, Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque – the two leading Cubist pioneers – are often credited with inventing the art of collage (or papier colle) during this phase in their career. The result of pasting real world textures and elements into art was a further flattening of the picture plane, removing the illusion of depth that we see in earlier Cubist art. This idea that items from the real world could be cut up and stuck into artworks rather than depicted with a brush was entirely new, and it opened up exciting new pathways into making art.

More Artists Were Involved in Synthetic Cubism

While the first phase of Analytical Cubism was essentially founded by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, by 1912 their radical ideas had attracted a wider pool of artists from throughout Europe and beyond. Along with Picasso and Braque these include Juan Gris, Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, Fernand Leger, Robert and Sonia Delaunay, Marcel Duchamp, Alexander Archipenko, Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Jacques Lipchitz, Natalia Goncharova, Mikhail Larionov and even Diego Rivera. They began taking earlier Cubist ideas and expanding them in new directions, experimenting with different materials, surfaces, colors and patterns.

We might even call Synthetic Cubism the fun younger sibling of Cubism, learning ideas from its serious analytical and intellectual elder and injecting them with an anarchic new spirit. Art in this school had a defined geometric, constructed feel, so even if it wasn’t made from collaged pieces, it was made to look that way. Sometimes artists did this by imitating the texture of found surfaces, such as wood grain or newspaper, into their art.

Synthetic Cubists Made Sculptures

While Analytical Cubism was generally a painting movement, Synthetic Cubism incorporated many new approaches to making art. These included collage, low relief construction and sculpture. In Picasso’s art we see how he made flat collages featuring newspaper cut-outs, paper doilies and other textured surfaces, before moving into cardboard constructions made with the same broad, flat planes of texture. French sculptor Raymond Duchamp-Villon made sturdier sculptures in cast bronze, but they have the same pieced together, layered quality typical of Synthetic Cubism, combining animal and machine parts into one.

Synthetic Cubism Was a Gateway into Lots of Other Art Movements

Synthetic Cubism broke new ground with its adventurous, subversive approach to image making, paving the way for numerous art movements to follow all across the world. These include Futurism, Constructivism, Rayonism, Dadaism, Surrealism and much, much more. Even today the influence of Synthetic Cubism can still be seen in contemporary works of art that explore elements of collage, construction and the incorporation of everyday items into art. Examples include Phyllida Barlow’s monumental constructions made from household junk. At the other end of the spectrum, John Stezaker’s eerie, spliced photographs transform found photographs into haunting art objects through the simple art of cut and paste first pioneered by the Synthetic Cubists.