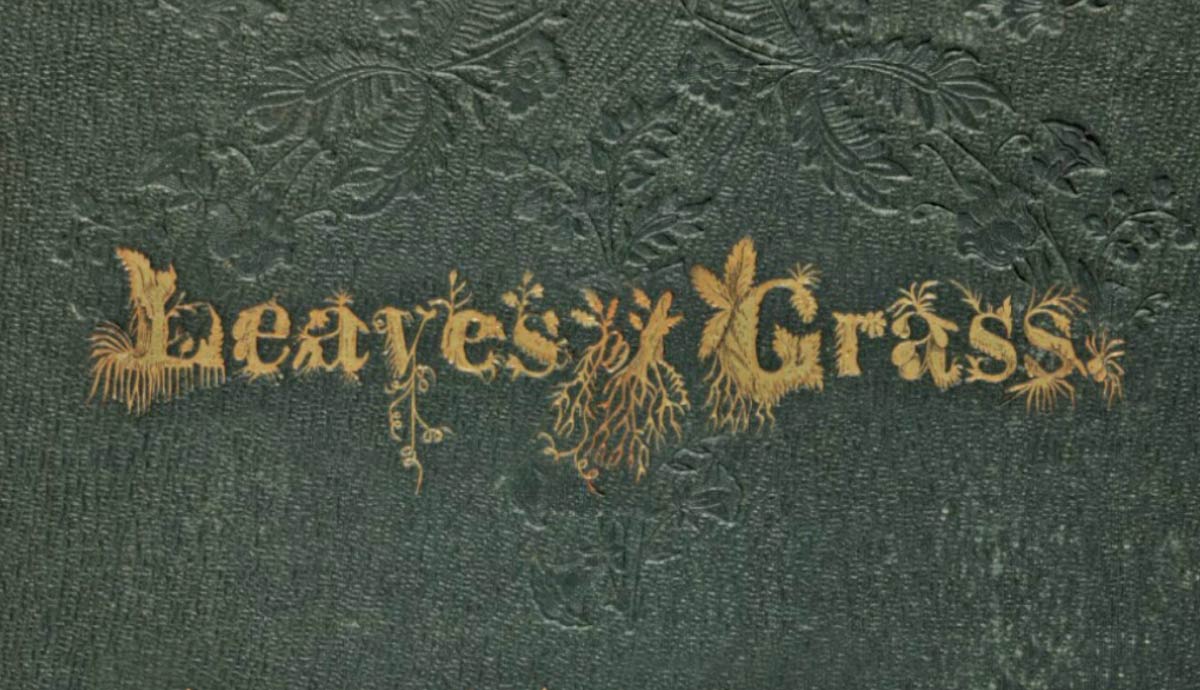

Walt Whitman is often considered the father of modern American poetry: a label he likely would have proudly stood behind in his lifetime. Having spent over 40 years writing poetry, he had strong intentions to insert his work into his nation’s literary canon and make the sensibility behind it conventional from the beginning. His choice to keep all his poetry in the same book is unusual to say the least, and it begs readers to ask what deeper meaning Whitman gestures at with Leaves of Grass.

First Release and Early Themes

Leaves of Grass was self-published in 1855, and contained only twelve untitled poems. Whitman took the initiative to not only print and distribute all the copies of this original release himself, but to bolster support for his work by writing positive reviews for himself under pseudonyms and printing them in newspapers. He would not need to act as his own critic for long, and as the years passed after the first release, awareness and acclaim grew side-by-side with increasing flack against it. Whitman would publish five new editions of Leaves of Grass, with occasional reissues, before finishing the seventh and final “deathbed” edition of the book, which contained over 300 poems and usurped all previous editions. Containing all his poetry under one title helps his readers see his work as he does: alive, growing, and indivisible. But how else does Whitman work around this theme of life?

The Contiguity of Life

These lines in Whitman’s longest and most notorious poem “Song of Myself” initiate a stream of conscious thought which demonstrates the far reach of his imagination. As much as Whitman relishes the color of the grass and the feel of it in his grasp or beneath his lie-down, he senses within the grass the phases and character of eternal life which came before it, guessing that the grass may be a child itself — “the produced babe of the vegetation” — or “the beautiful uncut hair of graves.” One of the key elements to Whitman’s sense of beauty is this omnipresent contiguity of life. Everything has immense value based on its belonging or participation in the unrelenting progression of life and creation, essentially making every individual form and fixture worthy of being adored in itself. The uniqueness of grass, like all else, is ancillary to the ubiquity of its substance.

Whitman recognizes his own place in this network of life, but does not describe himself so closely bound to it that he might dissolve into thin air at any moment. Part of Whitman’s aim with poetry, and reason for inserting himself in it, is to stand beside his readers and thoroughly help them grasp the breadth of existence as he has. This requires designating particular attention to human experience; and preserving space for the distinct wonder and beauty of the body to not be subsumed into the sum of all existence. This, however, leaves enough space for him to posture himself as more insightful or aware than his readers, even if it is well-intentioned:

“I am not an earth nor an adjunct of an earth,

I am the mate and companion of people, all just as immortal and fathomless as myself;

They do not know how immortal, but I know.”

Touching Life and Death

We don’t need to look beyond “Song of Myself” to trace how Whitman’s voice changes when he talks about the body and other people. Later in the poem, Whitman gives the following description of his own body and sense:

“To be in any form, what is that?

If nothing lay more developed the quahaug and its callous shell were enough.

Mine is no callous shell,

I have instant conductors all over me whether I pass or stop,

They seize every object and lead it harmlessly through me.

I merely stir, press, feel with my fingers, and am happy,

To touch my person to some one else’s is about as much as I can stand.”

When Whitman saw and felt the grass, his mind could move fast and loose through across space and time to envision and behold all the possible lives and forms which only now presents itself as grass. However, his fancy seems to slow down in the presence of another person.

Being Human

Whitman sees life all around him; it marks every feature of his world and points to a greater, singular force of creation which holds everything together with a warm embrace. However, he does not deny that being a human, and more importantly being with another human, comes with a more pronounced, overwhelming delight, as if the greater concentration of present life before him forces him to slow down and write with a more grounded sense of appreciation. Nonetheless, the thrill of life and love is never extinguished by the inevitability of death, and grass serves as a reminder that the opportunity to be, to feel and be felt, is never fleeting:

“The smallest sprout shows there is really no death,

And if ever there was it led forward life, and does not wait at the end to arrest it,

And ceased the moment life appeared.”

The title Leaves of Grass offers enough for readers to think on the magnitude of life and growth, and maybe peel back the layers of their present to cherish all that may have been before: an invitation to imagine ourselves freed from the confines of beginnings and ends.