Transcendentalism offers a worldview which unites the pursuits of individual peace of mind and a clear understanding of reality. Its emergence in a predominantly Christian nation means that while it incorporates a similar sense of spirituality, it serves as a secular alternative to religion by prioritizing a relationship with nature over a relationship with God. The novelty of Transcendentalism paired with the passion of its adherents to help the movement exert significant influence on American culture.

Origins of Transcendentalism

Transcendentalism draws influence from some of the tenet beliefs of Unitarianism, one of the more dominant and progressive sects of Christianity in 19th century America. Unitarian theology differs from other trinitarian sects like Catholicism and Lutheranism because it believes that God is a singular being. They encouraged practicing faith by reading the bible and molding an individual spiritual worldview, but nonetheless established a significant cultural presence across churches and universities in the United States.

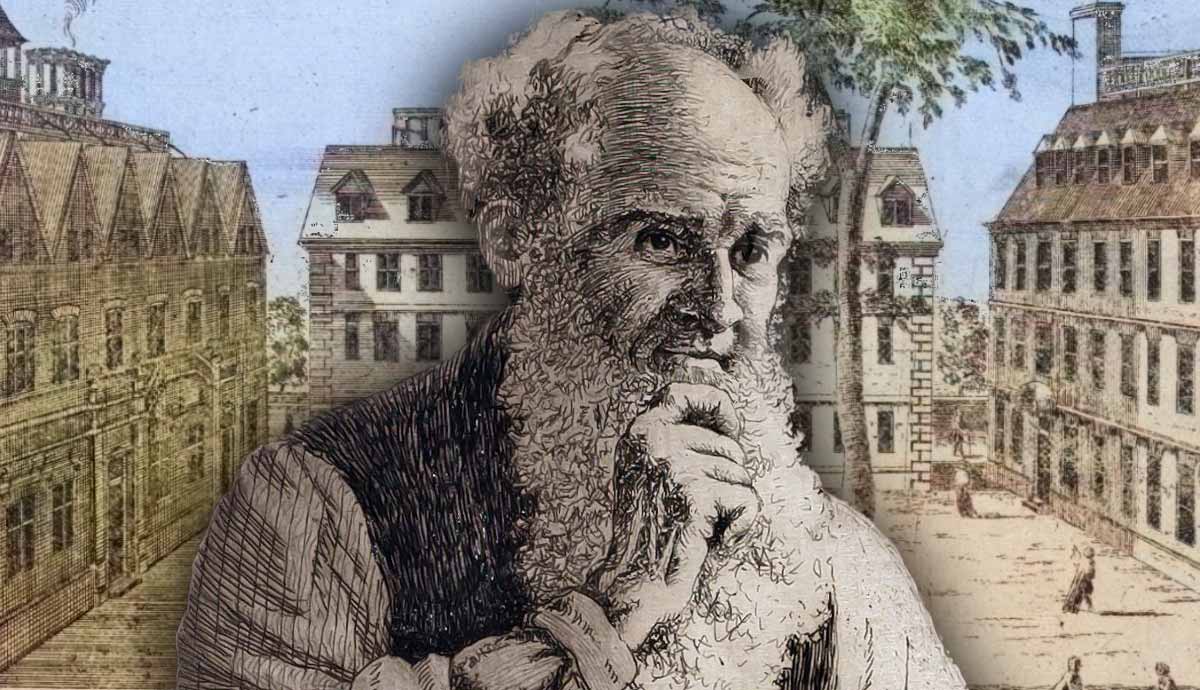

It was the main denomination at Harvard Divinity school where Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882) obtained a formal education in the tradition, after spending four years at Harvard college starting from age fourteen. Eventually, Emerson would publish his own beliefs, which separated him from Christianity and initiating the growth of Transcendentalism.

Emerson’s Nature

In 1836, Emerson wrote “Nature,” a book-length essay explaining the relationship between the individual and nature as means for connecting to God. Spending time in nature means solidarity; being alone with oneself without the business of society or the safety and comfort of home to influence thoughts. Getting away from the narratives about one’s identity shaped by these influences is the first step towards a certain kind of enlightenment involving discovery of internal and external purpose. As one observes nature, they see the simple existence of every natural being; plants, bugs, streams, and every other being acts in accord with its own nature, undisturbed by judgements of its own shortcomings or expectations.

Over time it becomes easier to see the bigger picture of nature to which everything contributes, and that being a part of this whole reinforces a sense of security and identity. Immersion into nature makes it easier to understand one’s true purpose and see themselves, as Emerson put, as “part or particle of God.”

The Infinitude of the Private Man

Emerson’s worldview encapsulates nearly every area of inquiry within the relationship between nature and the self. While this means that everything which isn’t the self can be explained as part of nature—even that which distracts people from nature like technology and civilization—it also emphasizes the power and potential of the individual. Emerson understands that the delight experienced from being in nature cannot come from nature itself and must be a product of either the individual or his/her harmony with nature. This is because we cannot completely separate our own activity, faculties, and inquiry from nature.

Language, beauty, morality, rationality, labor, all make it easier to see humanity and its conduct detached from nature, but any progress we make is essentially building up from nature. Complete understanding is only possible if nature is acknowledged in this way, and the infinitude of our own experience begins to mirror the intricacy and magnitude of nature.

Material Innovations

Most of Emerson’s essay focuses on how this conceptual reframing takes a unique character according to the object or area of focus. For example, the chapter “Commodity” discusses material innovations of man. Improvements in infrastructure, technology, and the efficiency and profit of producing and exchanging goods are natural processes insofar as they ensure the survival of man and work from the same natural mechanisms through which sustenance, shelter, navigation, etc. were possible in the first place.

Society improves to become more interconnected, more efficient, and bear greater resemblance to nature as a vast system of interactive parts. However, value is lost when such innovation is seen only for making life easier or more enjoyable. Emerson writes, “A man is fed, not that he may be fed, but that he may work.” The goal of human ingenuity is not merely solving the problems which make life harder, but rather to elevate the opportunity and potential individuals have to make a commensurate contribution to their world.

The Transcendentalist Movement

Emerson was aware of how important it was for his young nation to develop its own authentic cultural identity and was able to dedicate his later life to cultivating and mobilizing Transcendentalism. This included traveling throughout the United States and giving public lectures as a part of the Lyceum movement, but most of the growth of Transcendentalism happened in Concord, Massachusetts, where he shared a community with likeminded thinkers and writers. In 1840, the first issue of The Dial was released: a literary magazine including poetry, essays, and reviews from Emerson and his peers.

Some of the more notable Transcendentalists include Henry David Thoreau, whose writings mostly document immersion into the New England wilderness and the Transcendentalist lifestyle, and Margaret Fuller, who advocated women’s education and political rights, and would host public conversations to make intellectual discourse accessible to women. Other Transcendentalists include A.B. Alcott, George and Sophia Ripley, Frederic Henry Hedge, and Elizabeth Palmer Peabody.