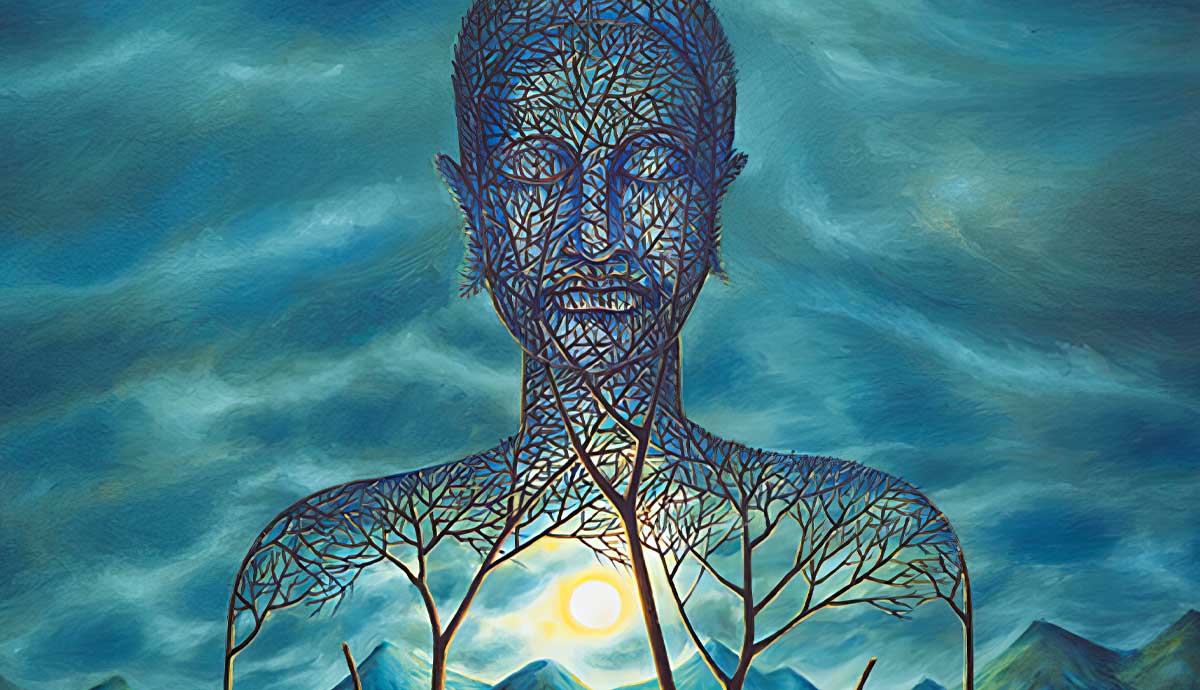

Carl Jung’s concept of the self radically contrasts with its formulation in other psychological paradigms. Lying at the center of the psyche, the self is the key that unlocks and resolves all aspects of Jungian psychology. “Know thyself” is one of the most misunderstood axioms in the contemporary world, where the boundaries of ego-consciousness are interpreted as the boundaries of ourselves. While Sigmund Freud was the first to suggest that there is more to ourselves than ego-consciousness, namely, the unconscious, Carl Jung dived much deeper into the heart of the matter. Jung discovered that the human psyche is vast beyond measure, for beyond the personal unconscious outlined by Freud was the mysterious, yet observable, realm of the collective unconscious.

The Conscious and Unconscious

The conscious, whose center of awareness is the ego, together with the unconscious in its personal and impersonal aspects constitute the self. The self is both the essence and the totality of the psyche, the unknowable and infinite whole that situates and unifies all of its opposing elements. The self is not only the regulating center of the psyche, “but also the whole circumference which embraces both conscious and unconscious” (Jung, 1962).

The scope of the self transcends the borders of the individual ego, meaning that it includes the person and an indefinite amount of other people. That is because the collective unconscious is identical in all individuals, and “out of this universal One there is produced individual a subjective consciousness, i.e. the ego” (Jung, 1951). The self is thus impersonal, yet embraces the personal ego. The ego is to the self as a part is to the whole, rendering the latter as the supraordinate prefiguration of the former.

It “is an archetype that invariably expresses a situation within which the ego is contained” and so it “cannot be localized in an individual ego-consciousness, but acts like a circumambient atmosphere to which no definite limits can be set” (Jung, 1951). True self-knowledge is thus knowledge of the totality, albeit often conflated with knowledge of the individual ego.

The Unity of Opposites

Every aspect of the psyche can be conceived in relation to the self as a part is to the whole, which is why Jung considers the self as transcendent. A closer look at Jung’s model of the psyche reveals how the self resolves the tension of opposites inherent within it. As the totality of the psyche, the self encompasses and unifies consciousness and unconsciousness, the personal and the collective, the anima and the animus, and the shadow and the persona. Due to its transcendent nature, the self “can only be described in antinominal terms”.

The Self as the Eidos Dei and the Imago Dei

Jung considers the self as the eidos dei, the essence of God, that is “behind the supreme ideas of unity and totality that are inherent in all monotheistic and monistic systems” (Jung, 1951). He insists that he discusses the self not as a metaphysical concept but as an empirical phenomenon, evident via the psychological observation of the contents of the psyche. As he remarks “I cannot prove to you that God exists, but my work has proved empirically that the pattern of God exists in every man and that this pattern in the individual has at its disposal the greatest transforming energies of which life is capable” (Jung, 1977).

The self is an archetype, a pattern of unity, wholeness, and totality that is imprinted in the psyche out of which ego-consciousness evolves and manifests in symbols. As a symbol, the self is indistinguishable from the imago Dei, the God-image. As Jung remarks, “all statements about the God-image apply to the empirical symbols of totality” (Jung, 1951).

According to Carl Jung, the symbols of the self are different expressions of the unified wholeness of man, whose psyche encompasses far beyond the limitations of ego-consciousness and personhood. The fact that its expression is referred to as ‘God’ is due to its numinous character, as evident in dreams, visions, and experiences of this kind. Jung writes that “wherever, therefore, we find symbols indicative of psychic wholeness, we encounter the naïve idea that they stand for God” (Jung, 1951). The symbol is thus mistaken for the symbolized.

Symbols of the Self

According to Jung, the symbols of the self are characterized by wholeness. As a rule, they appear to unite either two or four opposing elements, forming a dyad or a quaternion. The circle is an exception to that rule, for it has no beginning nor end, symbolizing oneness. The mandala, for example, was one of Jung’s favorite symbols of the self. Whatever pattern they follow, they symbolize the preestablished order and union of the psyche and are often experienced along the journey of individuation.

While symbols of the self could take infinite forms, Jung argues that the schemata of dyads, quaternions, and circles have always constituted every expression of the imago dei in all religious and mystical traditions along the course of human history. As Jung remarked in Aion, “The circle is a well-known symbol for God; and so (in a certain sense) is the cross, the quaternity in all its forms, e.g., Ezekiel’s vision, the Rex gloriae with the four evangelists, the Gnostic Barbelo (“God in four”) and Kolorbas (“all four”); the duality (tao, hermaphrodite, father- mother); and finally, the human form (child, son, anthropos) and the individual personality (Christ and Buddha), to name only the most important of the motifs here used”. According to him, “All these images are found, empirically, to be expressions for the unified wholeness of man”.