Masterpiece is a complex term. Its meaning has changed dramatically over time, giving it an entirely new definition in modern terms compared to when it first appeared in written language in the 13th century as chef d’oeuvre. Once a term associated with medieval guilds, it is now used to express that an artwork is an artist’s best work. So, what exactly is a masterpiece?

Chef d’Oeuvre: The Father of the Masterpiece

Masterpieces were first recorded in the late 13th century in France. Initially described as chefs d’oeuvre, or chief work in English, they were a concept associated with guilds and companies. A chef d’oeuvre was required when applying to join a guild. To be accepted, a person needed to produce a masterwork to demonstrate their skills and education. Apprentices would spend years learning their trade, living and working under masters who could teach them techniques needed in their field. Artists, goldsmiths, blacksmiths, weavers, apothecaries, cobblers, and carpenters were all required to make a masterpiece.

Once an apprentice could demonstrate that they had skills that others could not easily imitate, they earned their place in the field and deserved to be recognized as masters themselves. If someone was good enough to be a part of the guild, they were good enough to take on apprentices themselves.

In England, masterpieces were often called proof pieces. These proof pieces would often demonstrate all the skills needed to succeed. For example, a weaver could use all of the techniques they learned during their training to produce a singular piece where they could display all of their skills at once. It was similar to how artists use portfolios today when applying for jobs or gigs. It was a way to display skills and talents in one area.

The Nuremberg Goldsmiths Guild

In the 16th and 17th centuries, guilds shifted their requirements concerning masterpieces. Though masterpieces, at this point, still kept their original function of being pinnacles of the artist’s skill and training, the criteria for considering these works worthy of acceptance became more complicated. Classical values became more prominent in Europe as the Renaissance developed, and art specifically became more elitist. It was no longer satisfactory to simply master one’s work through technical skill. Art required more than technical skill now—it required outright virtuosity.

In Germany, columbine cups were one of the standard masterworks required for gaining admittance into the Nuremberg Goldsmiths Guild. They were named after their shape, which resembled a columbine flower. However, the Latin word it stems from, columbinus, means dovish, due to the shape of the flower resembling a cluster of doves. They are also occasionally called master cups.

Nuremberg was strict with bringing new members into their guilds. Not only were they required to create columbine cups, but applicants also had to make a set of golden rings and steel seal-die. The masterworks needed to be perfectly executed because if the guild rejected a masterpiece, the artist wasn’t always allowed to submit a work again. However, according to the guild’s rules, an artist could continue working as a journeyman in a workshop.

Giorgio Vasari

This shift in requirement could also have been influenced by the rise of prominent artists and writers like Giorgio Vasari who is considered the first art historian in Western history. Vasari created books and pamphlets on the best artists in Italy with the explicit goal of separating the better artists from the mediocre artists, therefore creating a hierarchy and changing the landscape of art history forever. Vasari’s writings would influence art history for centuries, creating a canon. His writings defined whose artworks deserved preservation, study, and funding. The pressure to be at the top increased, creating higher standards and requirements in the field as the top ranks became less reachable to those with fewer connections. Without connections in the art world, an artist would have to prove their worth more than ever before.

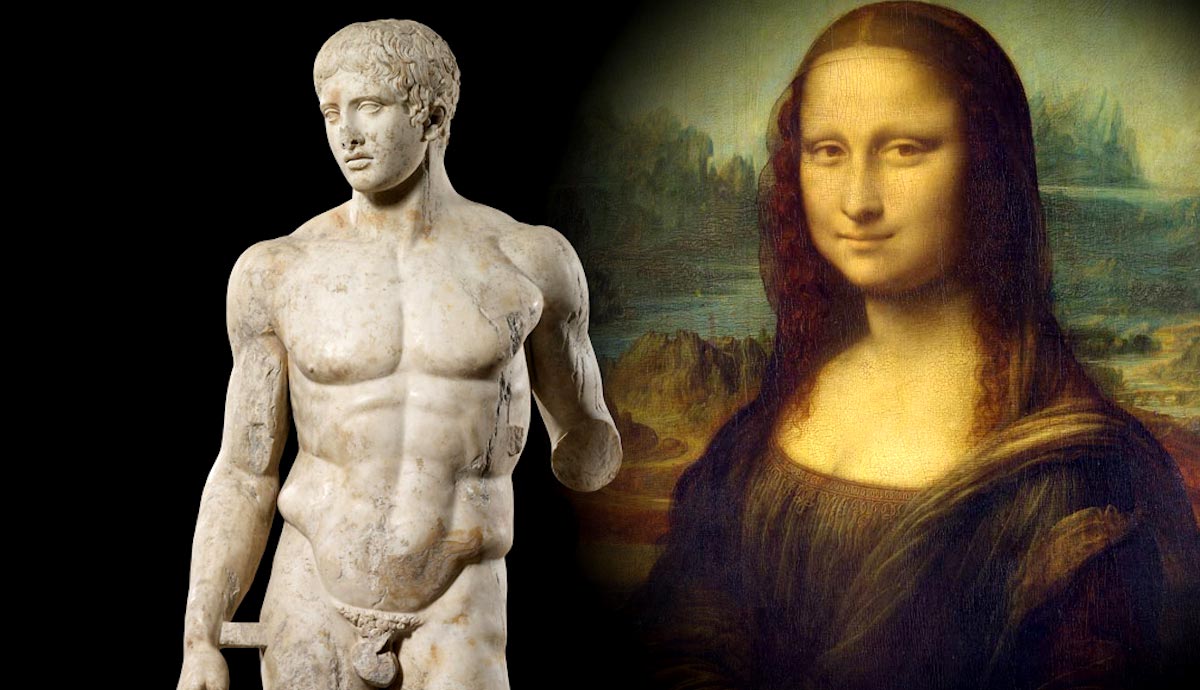

With the increase in classical values during the Renaissance and the shift to higher standards concerning masterpieces, artists were not able to simply learn from their masters during apprenticeships. Instead, they also had to learn about classical antiquity and look at classical examples of art to develop the skills needed to become a great artist. The best example of how this affected masterpieces is the ancient Greek statue The Canon by Polykleitos. The original Greek statue no longer survives today, but a Roman copy was found in Pompeii. It was initially titled Doryphoros, but the name was changed to The Canon when artists, especially sculptors, began looking at this particular statue as the ideal that was to be imitated.

When an artwork becomes a part of the canon, it follows a set of spoken or unspoken standards, more specifically a set of criteria from which it can be judged. It does so in a way that art history professionals, or pioneers like Vasari, consider ideal according to their values. The Canon (Doryphoros) is the Greek ideal of beauty and youth. The polished stone showcases smoothly carved muscles, a balanced and casual pose called contrapposto, and a harmony of limbs, angles, and measurement.

The Canon

As time went on and the 19th century came to a close, the word masterpiece began to take on a different meaning. In a casual modern context, a masterpiece can be anything when someone declares it one. This newer use of the word is often used in social situations or online. For example, you could catch this word in TikTok comments when someone calls a video overlaid with a voiceover or funky music a masterpiece because they enjoyed the content. A mother could also call an artwork made by her child a masterpiece.

On a more official level, however, the choice is not made by a social situation or even a member of the intended audience, but by institutions and their officials. Museum employees choose which paintings to take into their collection and, therefore, which paintings will be shown to the public. Similarly, museums choose which artworks are displayed under the highlight sections in their digital collections, telling viewers which artworks are worth clicking on. By doing this, institutions indirectly tell the public which artists are worth knowing more about.

Forever Changing Masterpieces

The art market has a similar effect as the institutions, though arguably much smaller. The market places more value on artists who are known and studied than on artists of equal talent and a lesser-known name, simply due to the economics of fame, stemming back to Vasari and making its way up through expensive purchases and prestigious institutions. The art market today is very different from the art market in the 15th century, for example. In the early 15th century in the Netherlands, artists like Petrus Christus used quirky tricks to show their talent to prospective patrons.

For example, in Portrait of a Cathusian Monk, there is a small fly painted on the frame of the artwork. It is put on the illusionistic frame specifically, to showcase Petrus Christus’s ability to create depth and paint hyper-realistically. The fly is meant to make the viewer take a second look to see if it is real. In doing so, it would be natural to realize the talent behind it if checking more closely was necessary. This was a brilliant marketing strategy people came up with while navigating a new and flourishing art market.

If considering an artwork a masterpiece can be so easily influenced by outside forces, rather than simply a general agreement on the quality of the work, the question becomes: can that masterpiece status be lost? A masterpiece is only sometimes considered a masterpiece from the moment of its completion. This could be due to various reasons, such as the painting going under-appreciated until the right person finds it and draws attention to it, the artist not releasing his artwork during his lifetime, and having one declared a masterpiece only after their death. However, can a masterpiece lose its status after being declared one by either an institutional power or through the nature of visual trends in society?

Artworks can decrease in popularity over time. Not all artworks have experienced this degradation of relevance, but some have, meaning a masterpiece can lose its masterpiece status someday. Even today, countless paintings that were once considered masterpieces are now rarely mentioned or displayed. This does not mean that an artwork becomes less important, it simply becomes less thought of due to the lack of relevance to contemporary societal values. In essence, if the public does not wish to see a specific artwork anymore, it will likely fade into obscurity unless there is some other aspect of the artwork keeping it relevant to modern interests.

After the invention of photography, the term masterpiece—in an institutional sense—became even more challenging to achieve, though the shift was subtle. Photographs replaced paintings in many ways, and many people began to question if painting, especially as a career, would become obsolete. Artists strived to maintain the importance of artwork in society by specifically creating artwork that was meant to showcase what painting could do that photography could not. In early photography, only the simplest of edits could be used to doctor photographs, while a painting could produce much more.

Masterpiece is a word that has shifted throughout its existence. Beginning in 13th-century France with the submission of a chef d’oeuvre for guild admittance, the guilds would eventually raise their standards in response to Vasari’s influence. The standards would continue to rise throughout the centuries, bringing us to the modern day when creating a masterpiece is still a challenge on a large, institutional scale, yet simultaneously a friendly way to share some love with a creator.