The United States Constitution’s Article II, Section 4 outlines the impeachment process, which grants Congress the authority to remove the president, vice president, and other civil officers for cases dealing with “Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.”

Since its inception, the House has initiated impeachment proceedings more than 60 times (with 21 impeachments). Yet, most Americans know it best when the subsequent trial deals with a sitting United States president.

Background

America’s Founding Fathers, who sat down in Philadelphia in 1787 to craft the United States Constitution, held a very pragmatic view on impeachment. There was a genuine fear that men could use the power for potential political abuse as a partisan weapon. Yet, most saw it as a necessary tool. Benjamin Franklin went as far as stating that in societies where no such democratic process to remove a person from power existed, it usually led to political assassinations. Thus, including one in the Constitution would be akin to potentially saving a life.

Because government officials should be held accountable for serious misconduct, the Founders followed the suggestion of Alexander Hamilton’s “Federalist Paper No. 65,” which stated that impeachment was most vital to preserving the new government’s integrity. To counter its potential misuse, the Constitution sets a high bar for conviction by requiring a two-thirds majority in the Senate, ensuring that only serious offenses warranted removal from office. Ensuring the intended vagueness for Article II, Section 4 to act more as a blueprint or a mechanism for future interpretation, the Founders added the unclear phrase “high Crimes and Misdemeanors.”

Process

The process for impeachment begins with a member of the House of Representatives who introduces a resolution or article of impeachment. The House Judiciary Committee then conducts an investigation, gathering evidence and holding hearings. Once the findings are in, the Committee drafts the formal impeachment articles outlining the charges against the accused official. The official is impeached after a debate on the House floor and more than fifty percent of the Representatives’ approval.

While many people mistakenly believe that being impeached is synonymous with being fired from the position, that is not the case. Impeachment is akin to being indicted in a criminal case that needs to go to trial. Following impeachment in the House, the process then moves to the US Senate, which then holds the trial.

If the trial involves the president of the United States, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court oversees the proceedings to ensure its impartiality. At the same time, the House managers act as prosecutors and present the case against the impeached official. The impeached person and their legal team can also present a defense, including calling on witnesses and presenting evidence to support their claim.

After the proceedings have ended, the Senate may remove the accused from office with a two-thirds majority vote of 67 out of the 100 senators. If the Senate does not reach this majority, the official remains in office, and the impeachment proceedings are officially over. It is essential to mention that the impeachment trial does not carry any criminal penalties unless the accused faces criminal charges in a separate judicial process after their removal following the impeachment.

There have been 21 impeachments, including three presidents, one cabinet secretary, and one senator, but only eight officials have been removed from office by the Senate.

Presidential Impeachment: Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson, known for becoming president after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln in 1865, had a very contentious relationship with Congress from the onset. His Reconstruction policies favored a lenient approach toward the former Confederate states, aimed at quickly restoring them to the Union. At the same time, the more radical Republicans in Congress sought to enforce stricter measures to protest the rights of formerly enslaved people. When Congress passed the Tenure in Office Act of 1867, partially to prevent the disliked president from firing Lincoln’s Secretary of State, Edwin M. Stanton, and Johnson fired him anyway, Congress began impeachment proceedings.

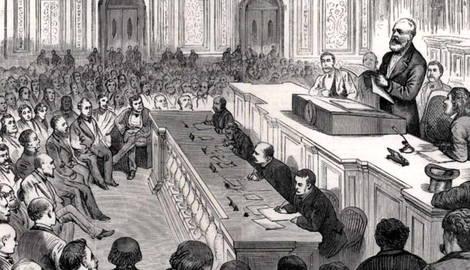

Following the House Judiciary Committee’s evidence, the House approved eleven articles of impeachment against Johnson on February 24, 1868, making him the first-ever president to be impeached. The following Senate trial and vote saw seven Republicans joining the Democrats in voting for acquittal, thus tipping the scales toward keeping Johnson in office by one vote. Although he remained in the White House, Andrew Johnson no longer held significant authority with Congress.

Actually Not Impeached: Richard Nixon

Although he fits into the narrative chronologically, President Richard Nixon was never formally impeached. Following the revelations of a conspiracy involving the president’s administration in the break-in at the Democratic Headquarters in Washington DC Watergate Hotel, the House Judiciary Committee approved articles of impeachment against Nixon for obstructing justice, abusing power, and contempt of Congress for refusing to release the Oval Office tape recordings incriminating him in the case. Yet, before the House could vote on the impeachment charges, Nixon resigned—a first in American presidential history.

Presidential Impeachment: Bill Clinton

Bill Clinton is likely best remembered in modern history not by his accomplishments or failures in office but by the single event that would make him only the second president in United States history to be impeached. Elected on the Democratic ticket in 1992, the president saw his high approval ratings from a period of economic prosperity overshadowed by accusations of extramarital affairs.

Clinton’s legal troubles began in May 1994 when a former Arkansas state employee, Paula Jones, filed a sexual harassment lawsuit against the former governor, which in turn led to an independent counsel, Kenneth Starr, being appointed to investigate the president’s conduct. As the investigation expanded beyond the Jones case in 1998, Starr came across evidence that Clinton had engaged in a sexual relationship with a White House intern, Monica Lewinsky.

The president initially denied having the affair. Congress then released Starr’s report, which also included allegations of perjury, obstruction of justice, and abuse of power, having found indisputable evidence that Clinton lied under oath about his relationship with Lewinsky.

The House Judiciary Committee approved four articles of impeachment against Clinton on December 11, 1998. With the final vote tally of 228 in favor and 206 against, the House voted to impeach the president the following week. When the Senate trial began in January 1999, Clinton’s defense team argued that the charges were politically motivated and that lying about the affair did not constitute the appropriate level of “high Crimes and Misdemeanors” required by the US Constitution. The Senate acquitted the president after a media-publicized trial with a final vote of 55-45. Clinton was censored for his actions yet allowed to remain in office, with many Americans seeing the impeachment as a partisan attack motivated by political interests rather than a genuine concern for the law.

Notable Non-Presidential Impeachment: William Belknap

Not all impeachments receive the same level of media scrutiny as presidential impeachments, yet even those less-known ones are notable in their own ways. Most historians point to President Ulysses S. Grant’s terms as some of the most corrupt in American history. Still, those very same scholars quickly point out that it was not the president’s fault but that of others within his administration. One of early history’s most infamous impeachment cases not directly involving the president occurred in 1876 under the former Civil War general’s watch.

Grant’s Secretary of War and former Union General, William W. Belknap of New York, held the office during some of the most tumultuous times in the nation’s history, the Reconstruction Era. Belnkap’s responsibility included managing the military affairs in the South, where the United States deployed federal troops to maintain order and protect the rights of formerly enslaved people. While a controversial post, especially in the South, Belknap held his own and garnered respect from most Northerners, especially former Abolitionists, and President Grant for a job well done.

However, things began to unravel when it was discovered that the Secretary of War secretly accepted bribes for granting military contracts. Each time John A.C.H. Cambell, who operated a trading post in Fort Sill, Oklahoma, received another federal contract, Belknap and his associates in the scheme would pocket kickbacks amounting to thousands of dollars. Because the Secretary of War’s actions were not isolated but involved collusion with other government officials and contractors, Belknap essentially oversaw, or some claim, headed, an extensive network of corruption within the War Department.

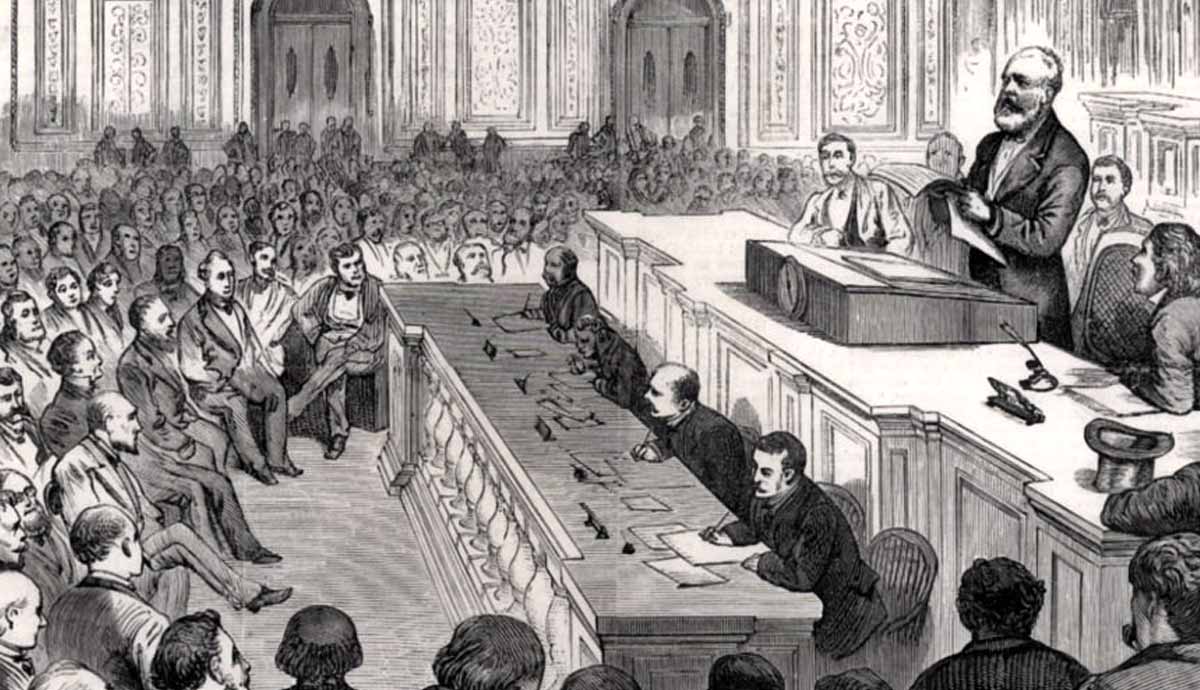

Following petitions and attorneys alleging corruption, the Congressional investigation was launched on February 27, 1876. The House voted to impeach Belknap on corruption, misuse of power, and failure to uphold the law, with the final verdict coming on March 2. Before the Senate trial began, the Secretary of War resigned to avoid removal and criminal prosecution. The Senate chose to proceed in an unprecedented move and a significant precedent. At the center of the trial was whether the Senate had the authority to try a former official, which the court decided was appropriate due to the ambiguity of the Constitutional wording.

After arguing that the charges against him were politically motivated and lacked sufficient evidence to warrant impeachment, Belknap was acquitted on May 26, 1876. As is usually the case, the vote fell along party lines.