In most contemporary locales, transport is something that is taken for granted. Resources such as medical supplies are generally easily accessible. However, in Alaska in the early twentieth century, freight was less reliable. Planes were utilized, but winter flying in primitive aircraft was a new concept that was still being ironed out. Ships were useful until harbors began to ice in, then became irrelevant for the season. Residents of Nome, Alaska, were used to this conundrum but were unprepared when a devastating illness affected the town in the winter of 1925. Little did they know, their saviors were four-legged.

Life in Nome

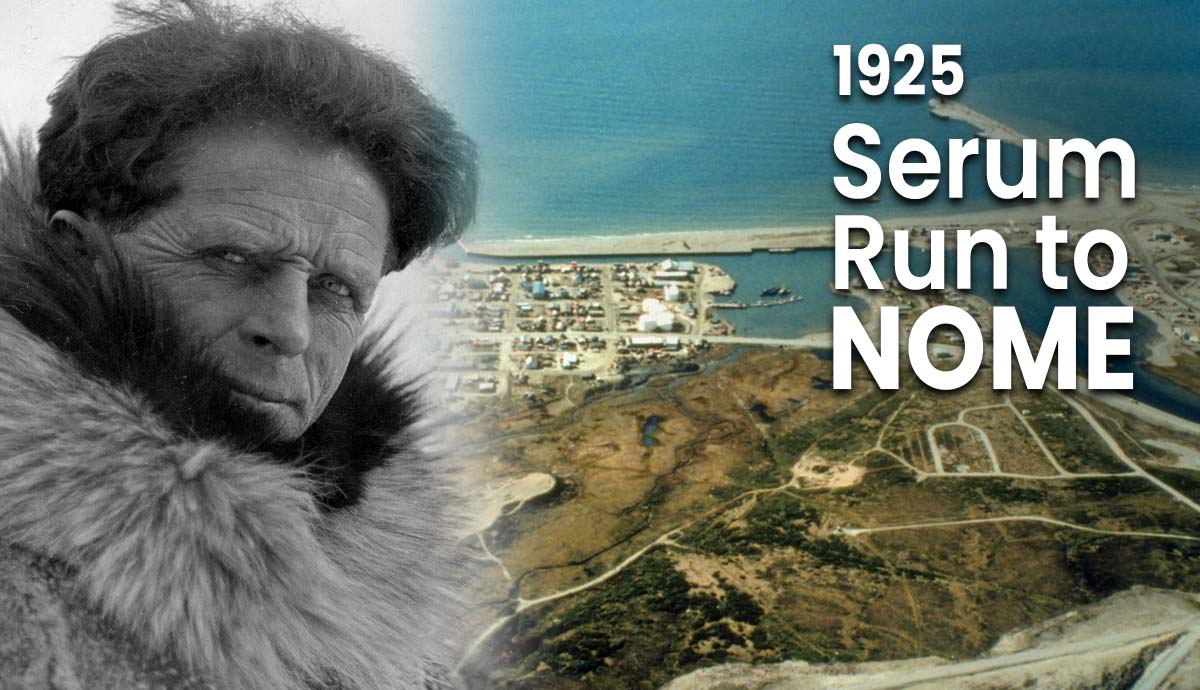

Nome, founded during the Klondike Gold Rush, once had a population of around 20,000 as gold seekers searched for riches. However, by 1925, gold resources had dwindled, and many had migrated. Around 1,400 remained in Nome, making a life in the isolated port city.

Located on the Seward Peninsula, Nome was bound by ice for seven months of the year, making shipping impossible. The closest railroad was close to 700 miles east in the town of Nenana. Commercial aviation was a few years from implementation in Alaska, and modern snowmobiles would not appear until mid-century. Small “bush planes” were being tested by enterprising pilots but had remained largely unsuccessful with their open cockpits in the brutal Alaskan winters.

The prime mode of transportation in winter in Alaska was a dog sled. The cold temperatures were too harsh on horses’ lungs, but dogs, particularly breeds like the Malamute and Siberian Husky, had been bred especially for this task.

Dogsledding appears to have originated with Indigenous populations in the Yukon, with the oldest archeological evidence pointing to its existence dating back to 1000 CE. Dogsledding, or mushing, was commonplace throughout Alaska by 1925, and formal racing was popular. Nome’s first dog race took place in 1908, and local mushers enjoyed minor celebrity as a result. Dogs were used to transport the mail, work on traplines, and assist hunters in hauling game.

Although it lacked transportation options, Nome was able to stay connected to the world with telegraph lines. Nome was the largest city in a post-gold rush Alaska, and when it wasn’t frozen, it was a busy port that was a hub for other towns to receive supplies.

More Than a Cough

In late December 1924, Dr. Curtis Welch, Nome’s only doctor, found himself examining a two-year-old Inupiaq boy who was experiencing labored breathing. Dr. Welch diagnosed the child with tonsillitis, as there were no signs of contagious disease in the boy’s village, nearby Holy Cross, or any symptoms that particularly alarmed the doctor.

Shockingly, the boy died the next day. The boy’s mother refused an autopsy. In the weeks that followed, respiratory illness among the area’s children occurred at a higher rate than normal, and three more children died.

As the number of sick children increased, Dr. Welch began to recognize the symptoms of diphtheria and realized a potential epidemic was on his hands. Diphtheria is a bacterial infection spread through respiratory droplets. It causes illness when the bacteria produce toxins as they multiply throughout the body. Though it is largely absent from the modern world thanks to vaccination programs, diphtheria was a devastating scourge in the early twentieth century.

The bacteria produce toxins in the respiratory system and kill healthy tissue. This dead tissue builds up and creates a thick coating in the throat, known to medical professionals as a “pseudomembrane.” This membrane-like structure impairs breathing and swallowing and can eventually cause suffocation. The disease also has the potential to damage the heart, kidneys, and other organs.

At the time, the treatment for diphtheria was to administer an injectable antitoxin that prevented the production of the compound that caused the symptoms and attacked healthy tissue. Dr. Welch had placed an order for a fresh batch of antitoxin to have on hand the prior year, but it had failed to reach Nome’s port before it was iced over. All he had to treat the cases at hand was expired medication.

After another child died, he decided to attempt to use the old antitoxin at a higher rate. Even with this treatment, another child died. Dr. Welch worked with town officials to arrange an emergency town meeting and impose a quarantine. He estimated he would need about one million units of antitoxin to prevent an epidemic in Nome.

Officials determined that units of serum were available in Anchorage, which was 1,000 miles away. The medicine could be transported as far as Nenana, approximately 674 miles away by railroad, but then the train stopped there. Planes were unable to fly in Alaska’s cold winters. The port was iced over. However, one of the townspeople’s most familiar and common forms of transportation could work: dog sleds.

Mark Summers, superintendent of the Territorial Board of Health, proposed using dog sleds to transport the serum. His original plan involved two mushers who met at a halfway point. However, Scott Bone, governor of Alaska, suggested increasing the number of involved mushers. He gave the US Post Office Inspector Edward Wetzler the job of organizing the final teams, as he was familiar with the best from mail transportation.

Some citizens were upset about the plan, fearing it was not the best option. Though planes struggled in the winter cold, some believed planes were much more likely to be successful than dogs. In fact, newspaper editor William Fendtriss Thompson, publisher of the Daily Fairbanks News-Miner, wrote caustic editorials on the topic, criticizing the organizers of the dogsled relay. By this time, about twenty more cases of diphtheria in Nome’s children had been confirmed, with about fifty others considered to be high risk due to their proximity to the infected.

Setting Out

William “Wild Bill” Shannon drove the first leg of the relay from Nenana. It was thirty degrees below zero Fahrenheit when Shannon lashed the twenty-pound case of antitoxin to his sled and set off for Nome on January 27. A high-pressure system was blowing in from the North, and Alaska suffered its effects.

Shannon’s team was led by his five-year-old dog, Blackie, but the balance of his nine-dog team was relatively inexperienced. As a result, Shannon diverted off the trail somewhat to smoother ice and ran alongside the sled at times to reduce its weight and keep himself warm. He arrived at his pre-determined rest stop in Minto at approximately 3 AM, with temperatures now dropping to colder than sixty below.

Shannon had frostbite on exposed areas of his face, and three of his dogs were struggling. After a brief rest, Shannon resumed his journey, leaving the three ill dogs behind. The musher and his six remaining dogs were in poor condition when they arrived in Tolovana at 11 AM. The serum was turned over to the next musher, Edgar Kalland, who, along with Dan Green and Johnny Folger, would move the package forward over the course of the next day and night.

Tragic Progress

On the 29, the serum moved between six teams and traveled 170 miles. However, two new cases of diphtheria had been reported and the weather continued to trouble the mushers.

On January 30, Charlie Evans set out in an icy fog with his team. Both of his lead dogs would perish on the run. Leonhard Seppala, one of Alaska’s most celebrated mushers, completed the most dangerous leg of the journey. He could not make it to Unalakleet in time to pick up the serum from the previous musher, but a local backup, Henry Ivanoff, was waiting there for this reason. Not far from Unalakleet, Ivanoff’s team ran into a reindeer and became entangled.

Fortunately, Seppala passed by him in the commotion, and the serum was transferred. Seppala’s team, led by twelve-year-old Togo, traveled 84 miles, covering the dangerous Norton Sound. They continued the next day, forced to climb Little McKinley Mountain, a 5,000-foot elevation increase.

At Golovin, the serum went to Charlie Olson, who suffered severe frostbite while blanketing his dogs.

The final musher, Gunnar Kaasen, and his lead dog, Balto, picked the serum up in Bluff. At one point, the sled flipped in the dark as a result of brutal winds. Kaasen suffered frostbite as he tore his gloves off to desperately recover the serum. The package remained intact.

Kaasen did not intend to be the last musher in the relay, but he found his successor, Ed Rohn, asleep and decided to finish the run himself. He assumed he could do it faster than Rohn could, accounting for the time necessary to prepare and harness a new team. Kaasen made it to Nome at 5:30 AM on February 2. The serum was thawed and ready for administration before noon.

Bravery Unmatched

There’s no telling what the damage to Nome’s population would have been in terms of death and suffering if it hadn’t been for the 1925 Serum Run and its brave participants. Fighting temperatures that reached as low as 85 degrees below zero, gale force winds, and blizzard conditions, the antitoxin was delivered to Nome in 127.5 hours, an unimaginable speed under even calm conditions.

To top it off, not a single bottle of medication was damaged or broken during the trip, thanks to the care of conscientious mushers. Thanks to their efforts, Nome never had to experience the horror of a pandemic.