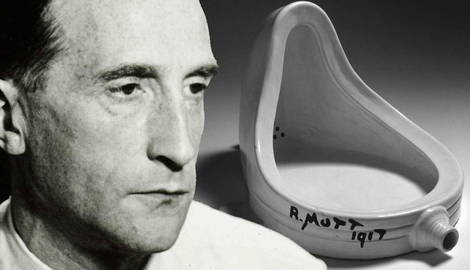

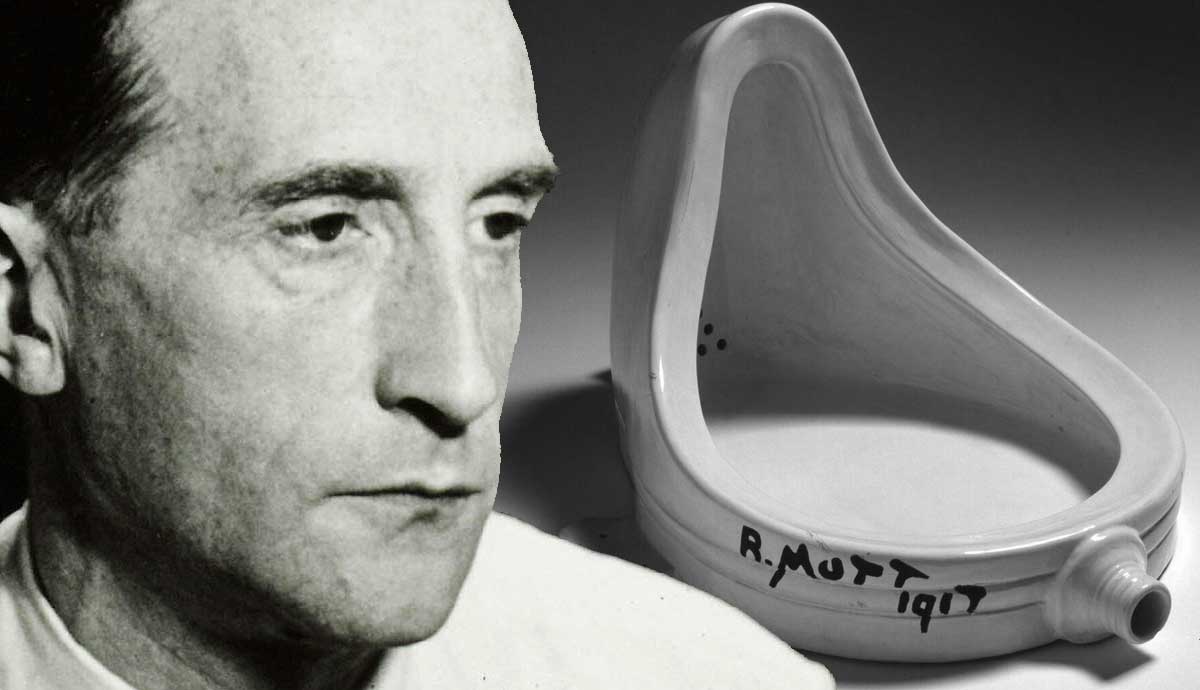

Marcel Duchamp was a pioneering conceptual artist, who poked fun at the art world with controversial and provocative artistic statements. From cross-dressing to spinning bike wheels and playing with string, he enjoyed upending the conventional with a nonsensical, Dadaist spirit. Most famous of all, however, is Duchamp’s Fountain, 1917, an upcycled urinal that he turned 90 degrees, signed with a strange pseudonym of ‘R. Mutt’ and displayed on a plinth. This bizarre object now has great historical significance. But what was so great about it? Read on to discover more about this icon of art history.

1. Duchamp’s Fountain Was the First Conceptual Artwork

Duchamp’s Fountain, made in 1917, is quite possibly the first ever conceptual work of art. Nowadays art galleries are filled with all sorts of weird and wonderful objects, but back in Duchamp’s day it was a far more traditional affair. Duchamp was one of the very first to bring manufactured objects – which he called ‘Readymades’ – into the gallery space. His Fountain was a particularly attention grabbing Readymade because it was such a crass, crude object (even if the one he bought was brand new). This was also important to Duchamp, because he wanted to subvert traditional good taste. He argued that anything could be a work of art, good, bad or ugly, as long as the artist chose it and called it art. In doing so, Duchamp demonstrated that the concept behind an art object was more important than the thing itself, and this became a cornerstone of Conceptual Art.

2. Duchamp’s Fountain Questioned Notions of Originality

Duchamp used his Fountain to upturn deeply entrenched ideas about art. One of the most important idea he questioned was the concept of originality. Before Duchamp’s day, artists were largely expected to produce one-off, original works of art, signed with the artist’s name to prove its authenticity. But Duchamp and his fellow Dadaists threw all this into question with the frequent use of found objects and multiples. In fact, with the encouragement of the French Surrealists, Duchamp went on to make multiple versions of Fountain in the 1960s, using the same type of urinal, and signing it with the same strange pseudonym. Duchamp even made a miniature version! While the original version of Fountain is now lost, the idea has lived on through these later multiples. Once again, Duchamp proved that the idea, or concept is more important than an original, hand-made object.

3. To Test the Boundaries Around Freedom of Expression

Duchamp submitted Fountain to the Society of Independent Artists’ group exhibition, a society for which he was a founding board member. The society claimed they would accept any work of art for display, rejecting the elitist formalism of Paris’s stuffy art institutions. But Duchamp wanted to use this artwork to see just how open-minded they really were, and if they really believed in the freedom of expression they claimed to promote. To hide his identity, Duchamp submitted the work under the name R. Mutt, signed crudely signed on the urinal in black paint.

Duchamp thought if he revealed that the work was by him, the other board members would accept it without question. But under an unknown name, the society had to analyze the object and the idea. When they rejected it for being indecent and immoral, Duchamp challenged the principles of the board members and their supposed tolerance to daring new ideas. Duchamp was one of the first to produce art under an anonymous pseudonym, but many more artists would follow his example.

4. Alfred Stieglitz Photographed Duchamp’s Fountain

After the Society of Independent Artists rejected Duchamp’s Fountain, he arranged for the esteemed documentary photographer Alfred Stieglitz to photograph his urinal. This photograph became an important artwork in its own right – Stieglitz might not have realized it at the time, but he was documenting a watershed moment when artistic values and traditions were called into question. The Dada periodical The Blindman published Stieglitz’s photograph along with an anonymous text, which argued, “Mr. Mutt’s fountain is not immoral, that is absurd, no more than a bathtub is immoral…He took an ordinary article of life…placed it under the new title and point of view [and] … created a new thought for that object.”