The cultures of the first-century Mediterranean world did not draw clear lines between civic and religious life as many do today. To say that Jesus was a Jew, thus, does not mean merely that he followed certain rules or participated in certain practices. Jews of his time did not see themselves as following a “religion” called “Judaism”. Rather, they considered themselves members of a chosen people who were playing a unique role in a story written by God. Jesus presented himself as the main protagonist of this Jewish story.

Jewish Rites of Passage in Jesus’s Childhood

Very little is shared in the Gospels about Jesus’s childhood. However, what is provided highlights Jesus’s Jewishness. Like all Jewish boys, he was circumcised eight days after he was born. According to the Hebrew Bible, God had commanded Abraham that all male members of his household would be circumcised as a sign of God’s covenant with him and his progeny.

While circumcision was not, from a strictly historical point of view, unique to Abraham or the Israelites, it was nevertheless perceived by Jews as a physical marker that set them apart from all non-Israelite peoples. In the context of Jesus’s day, in which Jews were particularly interested in distinguishing themselves from Greco-Roman culture, the practice certainly did the job since Greeks and Romans found it abhorrent. Jesus, thus, was identified as a Jew both ethnically and religiously almost from birth.

A second rite of passage through which all religious Jewish boys pass today is the Bar Mitzvah, a term meaning “son of the commandment.” This special ceremony is meant to mark the transition of a Jewish person from childhood to adulthood. A key moment in a Bar Mitzvah celebration is when the child reads a portion of the day’s Torah readings in the synagogue.

While the tradition of the Bar Mitzvah formally emerged in Judaism long after Jesus’s life, the Gospel of Luke in the New Testament tells a story in which Jesus, at age twelve, seems to reify his self-perception as an adult by reading and discussing the Torah with the Jewish teachers in Jerusalem. This suggests he participated in an emerging practice that would later become a typical rite of passage now seen in Jewish communities worldwide. Regardless, communal study of the Torah was an established religious practice in which Jesus participated throughout his life.

Jesus Observed Passover (Pesach)

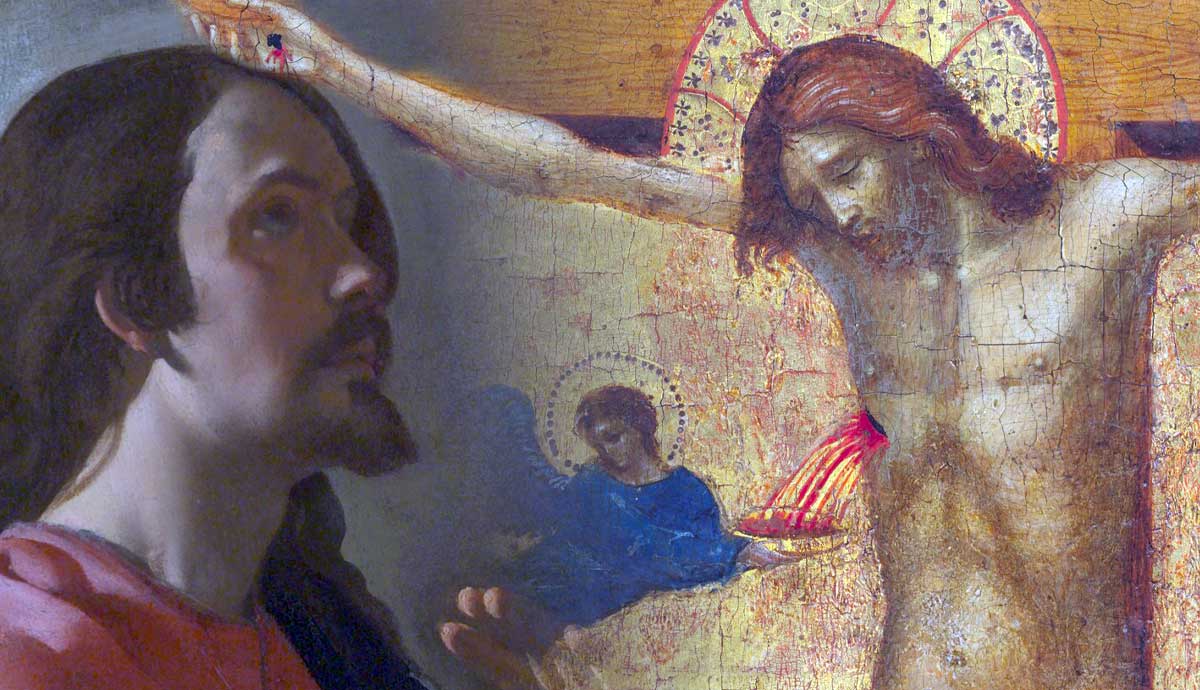

Jesus is presented in the Gospels as participating in annual Jewish celebrations. Specifically, the Gospel of Luke says that Jesus’s parents brought him to Jerusalem every year for Passover, a festival in which Jews remembered their exodus from enslavement in Egypt. This annual commemoration appears later in an episode in the story of Jesus now remembered famously as The Last Supper, a title perhaps most readily brought to mind today through Leonardo da Vinci’s painting of the same name. This was none other than the Passover meal, celebrated by all Jews.

Unlike all Jews, however, Jesus is presented in the Gospels as introducing a new meaning to this celebration, shifting its significance from the Exodus story onto himself. One of Jesus’s titles in the Gospel of John is the “Lamb of God,” evoking an analogy between Jesus’s death and ritual sacrifice. In several places, The New Testament alludes to the Passover sacrifice and animal sacrifice as metaphors for Jesus’s cosmic role in the salvation of humanity.

For those familiar with this New Testament trope, it is somewhat surprising that Jesus does not reach for the mutton on the table in the Last Supper in his now-famous reorientation of Passover’s meaning. Instead, he chooses the bread and the wine. He calls them his own body and blood and commands his followers to remember him whenever they eat and drink them in the future. The practice became a ritual known variously as “Mass,” “The Lord’s Supper,” or “Holy Communion” among Christian groups once Christianity became a distinct religious tradition and lost much of its recognizable ties to its origin in the Jewish Passover.

He Participated in Other Jewish Festivals

Jesus is also said to have traveled to Jerusalem with his disciples for the celebration of Sukkot, often called the “Feast of Booths” or “Tabernacles.” This seven-day festival was established as a reminder of Israel’s years of wandering after their escape from Egypt and before their entrance into the land of Canaan.

Jesus is also said to have been present in Jerusalem for Hanukkah, which memorialized the rededication of the Temple after a Jewish priest and insurgent leader named Judas (known later as “Maccabeus,” meaning “the hammer”) and his followers prevailed in their revolt against the Seleucids nearly 200 years before Jesus’s public ministry. Of all the Jewish holidays recognized by Jews in the first century, this one parallels most closely what would be today an independence day-type celebration, typically considered part of civic life in modern nation-states.

Jesus’s tacit participation in this event, thus, perhaps says as much about his political as his religious identity. The analogy to modern independence day celebrations, however, is mitigated by the reality of Rome’s dominance of historically Israelite lands in Jesus’s time.

He Interpreted Jewish Scripture

The Gospels neither go out of their way to put Jesus’s Jewish identity on display nor to set him apart from his non-Jewish contemporaries. Rather, he is assumed to have been a Jew who did what most Jews did in terms of religious practice. It was not until Jesus’s followers became a distinct religious movement after his death that Jesus’s Jewishness began to be overshadowed by the emerging “Christian” one. In the Gospels, he is presented as a Jew participating in normal Jewish practices but reinterpreting those practices as pointing to himself. This is especially true of Jesus’s engagement with Jewish scriptural tradition.

When it came to his approach to Jewish Scripture, Jesus is presented in the Gospels as radically different from other Jewish religious figures. Jesus spoke as if holy writ pointed to him, and as if the story of Israel found its resolution in him and his mission. The writers of the New Testament furthermore present Jesus as Israel’s representative, fulfilling Israel’s divine calling and embodying its priestly function.

Jesus and the Sabbath

Perhaps no tradition is more central to Jewish religious practice than Sabbath-keeping. The Gospels repeatedly picture Jesus in synagogues on the Sabbath day. The Gospel of Luke presents the inauguration of his public ministry as occurring on a Sabbath in Nazareth, Jesus’s hometown. Jesus is also portrayed as having been in frequent conflict with his contemporaries due to his practice of healing on the Sabbath. This is not necessarily surprising since one would expect Jesus, as a Jewish teacher, to engage in rigorous arguments with his compatriots about questions regarding Sabbath regulations.

Rigorous disagreement is a quintessential feature of rabbinic discourse. However, Jesus’s claim to be “Lord of the Sabbath” is another example of his tendency to redirect the meanings of Jewish religious practices toward himself, which would not have been normal for a Jewish teacher.

Was Jesus a Prophet?

While several texts outside the New Testament mention Jesus, they do not add new material to what is provided therein regarding Jesus’s religious life. While Jesus was called a prophet by many of his contemporaries, there is no indication that he aspired to be among the great writing prophets of the Hebrew Bible, such as Ezekiel, Isaiah, or Malachi. Although the Gospels present Jesus as studied in Jewish holy writ, they never suggest that he was a scribe — or even that he wrote anything at all.

In the New Testament’s presentation of him, Jesus does not see himself as coming to make a new contribution to holy scripture. This sets him apart both from Israel’s own writing prophets and also from future figures like Muhammad (Islam), Joseph Smith (Mormonism), Baha’ Allah (Bahai Faith), and others who inaugurated religious movements by claiming to have uncovered new or lost scriptures. Jesus, by contrast, assumed the validity and finality of the Jewish written scriptural tradition and is even recorded as insisting upon this.

In calling Jesus a prophet, therefore, Jesus’s contemporaries seem to have associated him with the work and mission of the so-called “former prophets” of Israel’s history, like Elijah and Elisha, who likewise played major roles in the life of the Israelite nation but to whom no biblical authorship was ascribed.

While the Gospels frequently claim insight into Jesus’s inner thoughts and feelings that might be considered part of his mystic religious experiences, the reader is virtually always left wondering how the authors became privy to them. None of the authors claims that Jesus kept a diary or employed a personal scribe. Moreover, it was also left to them to choose which of his public teachings and activities to include in their short accounts of his life.

Was Jesus a Priest?

Priests in Israel had to be from the tribe of Levi. Unlike in modern Judaism, ancient Israelites traced their lineage through the paternal line. By the same logic, affiliation with one of the twelve tribes of Israel likewise depended on one’s father’s identity. It is difficult, therefore, to address the question of Jesus’s priestly status without discussing the claim that he was conceived without male participation since the relevance of Joseph, the husband of Jesus’s mother, is cast in doubt.

The paternal line of Mary, Jesus’s mother, was from Judah. Her mother’s line was Levite, but this would not have mattered in determining Mary’s tribal affiliation. Joseph was likewise Judahite. The Gospels, and particularly Matthew, emphasize the importance of Jesus’s Judahite heritage because the Jews believed that their Messiah would come from the line of King David, and therefore would need to be of his tribe. The question of Jesus’s priestly status, however, is called into question as a result.

The New Testament contains an anonymous theological letter called the Epistle to the Hebrews in which the question of Jesus’s priestly status is addressed at length. It was, therefore, a question on the minds of at least some of the members of the movement that developed after his lifetime. Despite these questions, the Gospels themselves never present him as a priest.

Jesus’s Baptism Was a Jewish Ritual

John, known as the “Baptist,” was Jesus’s second cousin on his mother’s side. His father Zechariah was a Temple priest, meaning John could have served in the same role. John is known, however, for his ritual baptisms.

Baptism was a priestly function. John baptized people publicly in the Jordan River, which was not the typical venue for the practice in Judaism. However, baptism itself was far from uncommon as an Israelite ritual. Detailed instructions for priestly ritual washings and sprinklings, called “baptisms” in translation, are present in the Torah itself. The practice of full-body immersion appeared in later Jewish tradition in their use of the ritual bath called a mikvah.

Scholars are not sure whether John was pouring water over people or whether they were being fully immersed in the Jordon, partly because both practices had some precedent in Judaism. But regardless of the mode, Jesus’s participation in John’s unique baptismal rite would have been recognizably Jewish. Though baptism’s association with Christianity became widespread later, it was not a Christian invention and Jews continue to use the mikvah today.

He Was Zealous for Temple Purity

The Gospels report Jesus spending considerable time in the Temple, where he taught and healed the sick and infirm. The most well-known incident occurring in the Temple in Jesus’s life, however, was when he drove out money changers and animals from the Temple court. It is not clear whether he did this on one or two occasions. Jesus’s zeal for the Temple’s purity would have been appreciated by many of his Jewish compatriots who shared his belief that it had been corrupted by the greed of the Temple authorities.

A statement regarding the Temple was presented among the accusations of blasphemy that led to Jesus’s crucifixion. Jesus is presented as predicting the Temple’s destruction. Even though the Temple was destroyed within the lifetime of the Gospels’ authors, Jesus’s statement is interpreted by the writer of the Gospel of John as a metaphor for Jesus’s own body and, thus, as a prediction of his own execution.

Religious or Political Figure?

All four of the Gospels report that Pontius Pilate commanded a sign be fastened over Jesus’s head on his cross reading, “King of the Jews.” This identified the primary charge against Jesus and explained at least one important motivation behind his execution from the Roman perspective. Jews under Roman rule hoped for a king who would deliver them from Roman dominance and usher in a theocratic era of freedom and restoration. By mocking Jesus’s alleged claim that God’s kingdom had been inaugurated through his ministry, Pontius Pilate was mocking both Jewish political and religious aspirations together.

While Jesus is usually seen as a religious figure today, his culture would not have seen a clear divide between religious, political, and civic categories generally speaking. Jews had a particularly earthy faith, and their expectation was that divine activity would manifest in overtly political ways. Biblical prophets were unapologetically involved in Israel’s political life, often functioning as a check on kingly power. While priests were confined largely to Temple service in ancient Israel, after the Maccabean Revolt—which had been led by the priestly family of Mattathias—the priesthood functioned in unmistakably political spheres, if with varying degrees of power. Famously, the “priest-king” or even priest-conqueror role had become a recurring trope in the centuries leading up to Jesus’s day.

Note: The acronym “INRI” often seen over Jesus’s head in depictions of the crucifixion in Western art represents the first Latin letters in the phrase, “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews.”

Several of Jesus’s titles, such as “lord,” “Messiah,” and “king” have openly political connotations. A title favored by his disciples was “teacher.” But they seldom preferred to call him a prophet and no one considered him a priest during his lifetime. Thus, despite Jesus’s later categorization as a religious leader, in his own lifetime, his political role was at least as important to both his friends and his enemies.