The year 1603 marked the beginning of the Tokugawa Era in Japan, also known as the Edo Period. The era began as Japan secluded itself for over two centuries, becoming a mystery. Yet during this period of monumental change the country’s culture flourished like never before, with great developments taking place across the arts, business, and wider Japanese culture.

The End of Chaos

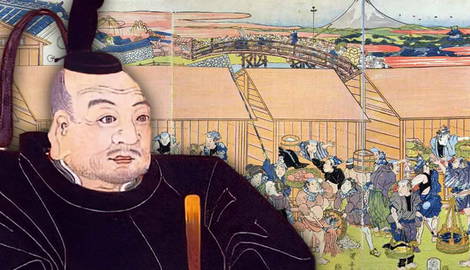

In 1600, Japan’s two biggest rivals, Tokugawa Ieyasu and Ishida Mitsunari, clashed at Sekigahara. Ieyasu won, eliminating his opponent, becoming Shogun, and taking over the bakufu (military government). Japan now only had one government.

Tokugawa’s victory ended the Sengoku Era, or “Warring States” period, which originated in the 1460s. As the wars ended, the Tokugawa clan established themselves in Edo, later Tokyo, taking it as their capital by 1603. The Tokugawa Bakufu’s grip on power remained absolute until the 1860s with their brand of government. Tokugawa had cemented his reputation as one of Japan’s three “Great Unifiers.” Much of modern Japan formed under the Tokugawa rule from business, culture, and arts.

Transformation and Edicts

The first changes the Tokugawa Bakufu wrought were strict control over foreign trade, a rigid class structure, religion, and even the noble class, or daimyo. The first significant edict came in 1612 banning Christianity, which the Bakufu feared would subvert a control over the population. The choices Japanese Christians faced numbered only two: conversion or martyrdom. The failed 1637 Shimabara Rebellion effectively ended Christianity in the Empire until 1873.

Next, the Bakufu subsequently enacted sakoku, or “closed country,” in the 1630s. Foreign travel was banned, and trade restricted to ports like Nagasaki. Nearly all foreigners were expelled except the Dutch and Chinese; any others were considered trespassers, and those caught typically executed.

The Bakufu rightly feared the daimyo, as these men wielded much power and money. To siphon these off, sankin kotai or alternate attendance policy became the norm. Daimyo were forced to build extravagant residences in Edo, where they lived for one year away from their domain. Their families remained as hostages in Edo when the daimyo traveled home. Also, each domain supplied soldiers to the Bakufu, placing an additional expense to strain the daimyo’s finances.

Post-1630s, the Bakufu enforced a strict class order of samurai, farmers, artisans, and merchants at the bottom. Officially, mobility between the classes became forbidden. Despite their bottom rung, merchants earned money from trade, which bought some relief. The new social system aimed to promote social and political order, but with the Bakufu’s hideously expensive sankin kotai system, many samurai fell into debt. In Edo Period Japan, only the merchants possessed cash to lend. By 1640, Japan’s isolation was complete, ending most external influences.

Genroku: Culture Achieved

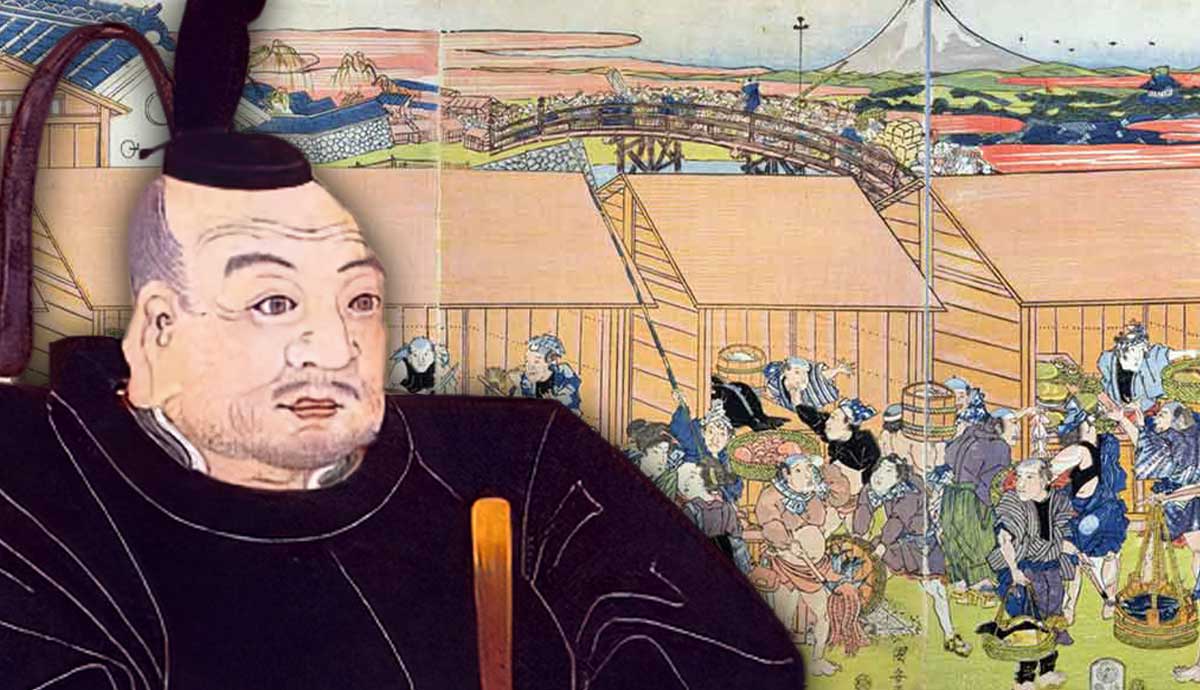

Prosperity increased after the Bakufu’s seclusion policy, especially in big cities like Edo, Osaka, and Kyoto. This took time, but by the 1680s as 1688 to 1704 became known as the Genroku Era. This Era led to renowned developments in varied art forms such as kabuki theater, which poked fun at society, bunraku puppetry, and haiku poetry. Ukiyo-e, or woodblock prints, evolved too, later becoming world famous in the 19th century west. This art form displayed Japanese society, thoughts and impressions. Popular themes were nature and town life.

The most sampled ukiyo-e, even over a century later, is Hokusai’s Great Wave off Kanagawa. Though drawn after the Genroku Era’s high, this image still demonstrated Japanese thoughts and inspired many Impressionists. The Wave is seen as representing a change in society and increasing foreign contact with what disruptions could affect Japan. The Genroku Era’s influence lasted for years in insulated Japan.

Stability Means Success

With Japan united, the Bakufu implemented trade policies and built roads to encourage trade. The economy grew, along with the population, agriculture, and literacy. Thus, the demand for entertainment escalated. The daimyo’s castles, already administrative centers, became towns where a rising middle merchant class and artisans settled along with manufacturing. Some of Japan’s biggest companies, like the Sumitomo Group and Mitsui, started during the Edo Period.

Foreign Influences

The Tokugawa Bakufu’s official ban on foreigners did have cracks. Through Dutch traders at Nagasaki, books on botany, anatomy, technology, and science reached scholars, some even legally. By the early 1800s, even the Bakufu realized they needed Western knowledge. The official term for Western learning was “rangaku,” or Dutch learning.

Cracks Appear

Japan’s isolation lasted for nearly 250 years, with little trouble aside from some foreign probings or peasant rebellions. But by the 1850s, an economic decline, forced treaties under military threat, or political intrigue ended sakoku. Civil war broke out in 1868, sparking the Meiji Restoration and ending the Edo Period. Despite the seclusion, Japan’s economy and society benefitted, gaining breathing room from intrusive European powers.