The Great Migration was the mass movement of Black Americans that took place between 1910 and 1970 in the US. The migration occurred in two phases. The First Great Migration was the mass movement of Black Americans between 1910 and 1940, while the Second Great Migration occurred between 1940 and 1970. The migration was fueled by a number of factors, including racial discrimination and oppression in the South and better opportunities that industrialization and wartime efforts provided in the North. Millions of African Americans migrated to major cities in the North and later in the West to escape the great number of disparities in the South and to seek personal freedom.

Roots of the First Great Migration

The first great migration was a culmination of Jim Crow laws in the South, industrialization in the North, and the first World War. There was a great amount of hostility in the South following the Civil War. The war devastated the South’s economy, and the abolishment of slavery introduced a new social system that strong supporters of the Confederacy didn’t want to recognize. Efforts to integrate African Americans into daily life and labor systems in the Reconstruction era weren’t very successful.

Jim Crow laws were introduced as a means to oppress African Americans, and the discrimination laws were upheld when the Supreme Court deemed “separate but equal” constitutional in the Plessy v. Ferguson case. Despite the passage of the 14th Amendment, which granted citizenship to formerly enslaved peoples, many African Americans still found themselves indebted to whites. Establishing personal freedom and independence in the South was difficult.

Some African Americans turned to sharecropping or tenant farming to make a living. However, the cotton market suffered greatly due to the Civil War, and crop failures further strained the economy. As a result, sharecroppers became indebted to landlords by making agreements to work for a defined number of years to make up for the losses that were usually through no fault of the sharecropper.

Industrialization in the North opened up more jobs in factories and mines. Although wages were low and working conditions were poor, it gave many people the opportunity to enter the working class. World War I opened up even more positions as millions of men left their jobs to serve in the war. The North also offered better educational opportunities for children. Little money was allocated to African American schools in the South. Teachers were paid less, and the facilities weren’t in good condition. Many African American students at the time didn’t continue their education past the sixth grade, as many went to work to help support their families. Attendance requirements and more funds for schools in the North encouraged students to continue their education.

African American-owned newspapers like the Chicago Defender often published articles encouraging African Americans to move out of the South. Many in the South wrote letters to the Chicago Defender to seek advice on how to make the move and establish themselves when they arrived. The bustling cities in the North were also less personal. Although race riots and discrimination still occurred, city life offered a more impersonal lifestyle that greatly differed from the unified communities in the South.

The First Wave of the Great Migration

Larger numbers of African Americans began moving to the North in 1910. Smaller numbers migrated during the Reconstruction period to nearby states, but a bigger influx was triggered by harsh Jim Crow laws that were heavily enforced in the South. African Americans mainly moved to major northern and midwestern cities, such as New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago, in the first phase of the migration. The number of migrants increased significantly again when men were drafted into World War I in 1917.

The US Department of Labor established the Division of Negro Economics to collect data on the migration between 1916 and 1917. According to the report, it’s estimated that 50,000 African Americans migrated from Georgia, 90,000 migrated from Alabama, and 100,000 migrated from Mississippi. The number of migrants continued to rise in the years that followed. Many reports state that at least 150,000 African Americans migrated to the North in 1923.

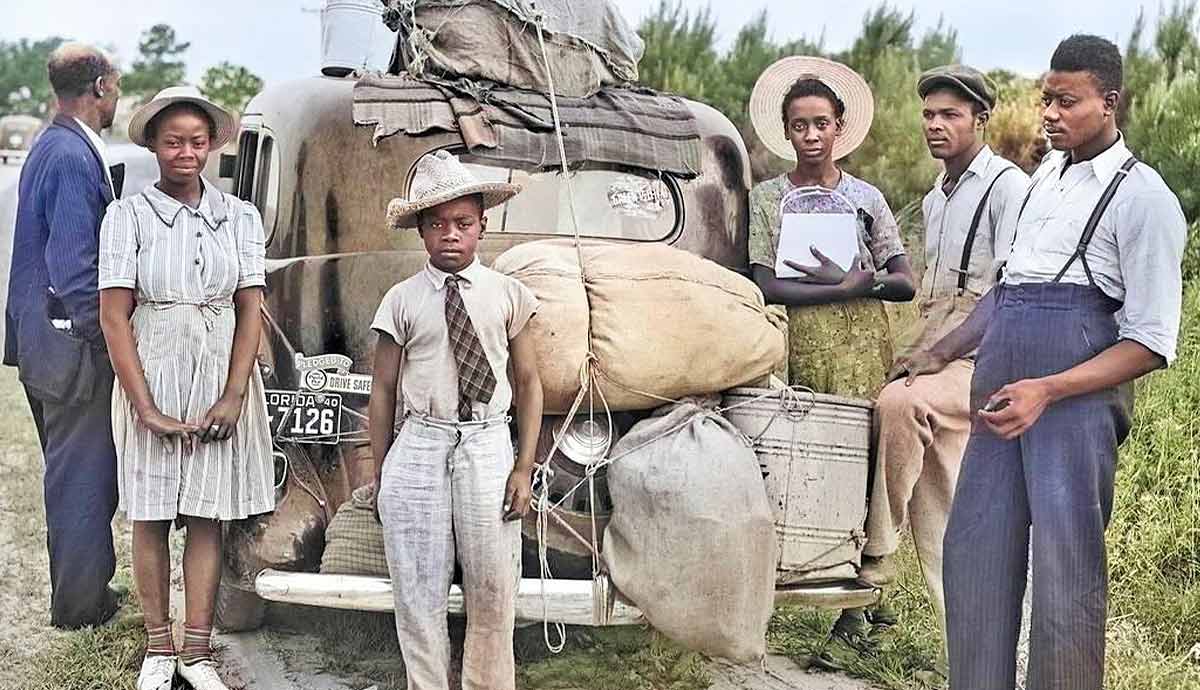

The development of the American railway system also allowed for easier long-distance travel. Migration patterns of the First Great Migration followed major railway routes. Travel by bus became more common in the 1930s when Greyhound Lines became a major interstate bus system.

Employers from the North made an effort to recruit African Americans in the South by creating newspaper ads. Recruiters were also sent to the South to find African Americans who would be willing to relocate, with the promise of better-paying jobs. People who migrated north also sent letters to friends and relatives in the South expressing the advantages of leaving. In just five years, between 1915 and 1920, about 500,000 African Americans migrated north. In the 1920s, an additional 750,000 to one million African Americans followed suit.

In total, about 1.8 million African Americans migrated from the South between 1900 and the late 1930s. Major cities in the North and Midwest that saw the largest increases in African American communities during the first wave included Chicago, Detroit, New York City, and Philadelphia. When the Stock Market Crash of 1929 led to the Great Depression, migration numbers reduced until the second phase.

Outbreaks of Racial Unrest

Racial tensions began to grow in the late 1910s and continued into the ‘20s as military men returned home from World War I and found that their positions were filled. The Red Summer of 1919 was one of the most widespread outbreaks of racial violence caused by these tensions. Race riots occurred throughout the South, the Midwest, and the North.

The first confirmed Red Summer race riot took place in Millen, Georgia on April 14, 1919. Church buildings and lodges belonging to the African American community were burned. Six fatalities were reported, four of which were Black men and two white officers. The deadliest incident, known as the Elaine Massacre, occurred in Elaine, Arkansas on October 1, 1919. About 100 African American sharecroppers were attending a meeting at a church when shots were fired. There was fear that the group was meeting to plan an uprising, and a mob gathered shortly after the gunfire. The incident resulted in the death of at least 100 African Americans and five white men.

Several race riots broke out in Chicago in the Red Summer of 1919. One of the largest riots in Chicago was caused by heightened tensions and the drowning of a 17-year-old African American boy named Eugene Williams. At the time, Lake Michigan was segregated by an invisible line to separate African American lake goers from whites. Williams and his friends were swimming in the lake when they crossed the line. A group of whites began pelting stones at them. One of the stones struck Williams and caused him to drown. Violence ensued for days, and shootings, fires, and beatings caused the death of 23 African Americans and 15 white people. About 537 people were injured.

Martial law was declared in Tulsa, Oklahoma by Governor James B.A. Robertson in June 1921 when a riot broke out. The riot, known as the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, was started by an angry mob that surrounded the courthouse where Dick Rowland was being held. Rowland was arrested for being in an elevator of the Drexel Building with a white woman on May 30. The accusations for what Rowland was being held for were unclear, but rumors spread that he had assaulted the woman while in the elevator.

As rumors made their way throughout the white community, law enforcement decided to arrest Rowland the following day so they could conduct an investigation. A mob gathered around the courthouse, and gunshots were fired. Violent beatings and arson continued into the following day. The 24-hour incident resulted in more than 800 injuries and at least 36 deaths, but it’s believed there were many more fatalities.

The resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) in the 1920s also contributed to the increase in racial violence. The reappearance of the KKK was primarily fueled by the film entitled Birth of a Nation, which depicted the KKK in a positive light. The film was released in February 1915. In November, a rally was held by Colonel William J. Simmons on Stone Mountain, which involved the burning of a cross to signify the KKK’s re-emergence. By the mid-1920s, there were millions of KKK members spread across the nation. Membership numbers began to die down in the 1930s.

The Second Great Migration

The second phase of the Great Migration began in the 1940s, particularly due to World War II. Larger waves of African Americans moved to the North in the Second Great Migration, but many also moved westward. Approximately 1.5 million African Americans moved to northern and western cities throughout the 1940s. African Americans who moved out of the South in the Second Great Migration did so for many of the same reasons rooted in the first phase of the migration. As railroads and bus lines became more interconnected, traveling became quicker and easier. California was a popular destination for many African Americans moving West. By 1950, counties in California with more than 50,000 African Americans included Los Angeles, San Bernardino, Riverside, Imperial, Tulare, and Monterey.

While hundreds of thousands of African Americans moved out of the South each decade in the First Great Migration, almost every decade afterward, beginning in the 1940s, involved more than one million migrants. The African American population in New York City jumped from 4.7% in 1930 to 21.1% in 1970. Detroit’s African American population more than quintupled from 1930 to 1970. In the midst of the Second Great Migration, African Americans and civil rights supporters launched the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s to fight against segregation and push for justice and equality. Large-scale protests, such as the Freedom Rides of 1961 and sit-ins, helped pave the way for the end of Jim Crow laws and more equal opportunities.

Impacts of the Great Migration

The Great Migration had several impacts on the northern and southern regions of the US. The South suffered economically, as many farm workers and laborers left their jobs to seek higher wages in the industrial world. The South was still in major recovery from the Civil War. The push toward a more industrialized way of life and natural disasters, such as floods and boll weevil attacks, depressed the agricultural industry even more. The Great Depression took its toll on southerners as well. The South wouldn’t see a rebound in its economy until the 1980s. On the other hand, the North experienced exponential growth between the Roaring Twenties and the Consumer Era of the 1940s to the 1970s. The social, political, and economic systems of the North were experiencing major change as a result of the Great Migration.

The Harlem Renaissance bloomed primarily in New York City but also in other major northern cities, united African American communities, and offered opportunities for artistic and intellectual expression. Notable African American artists, intellectuals, and entertainers that emerged in the Harlem Renaissance included Langston Hughes, Aaron Douglas, Zora Neale Hurston, Josephine Baker, and Duke Ellington. The Jazz Age had a major influence on rhythm and blues and rock ‘n roll music, which emerged in the 1940s and ‘50s.

The Great Migration still has its influences on the present day. Some of the major cities that African Americans migrated to throughout the decades in the 20th century consist of majority African Americans today, such as Detroit and Philadelphia. In total, approximately six million African Americans left the South during the Great Migration.