The Mason-Dixon Line is a standard boundary in the collective minds of Americans. It separates what was and still is the South from the North. Most believe this line indicated the beginning of the Confederate States of America, which seceded from the Union and ultimately started the American Civil War. However, the history of the Mason-Dixon Line goes deeper than the Civil War. Today, it often symbolizes the divide between the North and South geographically, socially, culturally, and politically. Here, we will look at the significance of the Mason-Dixon Line in United States history.

Why Was the Mason-Dixon Line Created?

The argument began over two colonies: Maryland and Pennsylvania. Maryland was chartered in 1632, and the land was granted to Cecil Calvert. King Charles II granted William Penn the charter to Pennsylvania. The problem lay in the land between the 39th and 40th parallels.

The map that King Charles and William Penn had relied on to build the charter was inaccurate. They believed that the Northern border of Maryland and the Southern border of Pennsylvania were the same. In reality, the Northern edge of Maryland sat further north than previously thought, thus encroaching on Penn’s territory and his already established capital of Philadelphia. Any compromise to resolve the dispute was nullified due to Penn receiving the lower three counties of Delaware Bay. Maryland considered these counties part of its territory, and a decades-long battle ensued.

The problem remained unsolved throughout the 1730s, as the two families reached tentative agreements and went back on them until the 6th Baron Baltimore, Frederick Calvert, gave up his claim on the disputed lands. The Penn family agreed to a solution: to survey the land surrounding the established border between Maryland and Delaware and create a border 15 miles south of the southernmost house in Philadelphia.

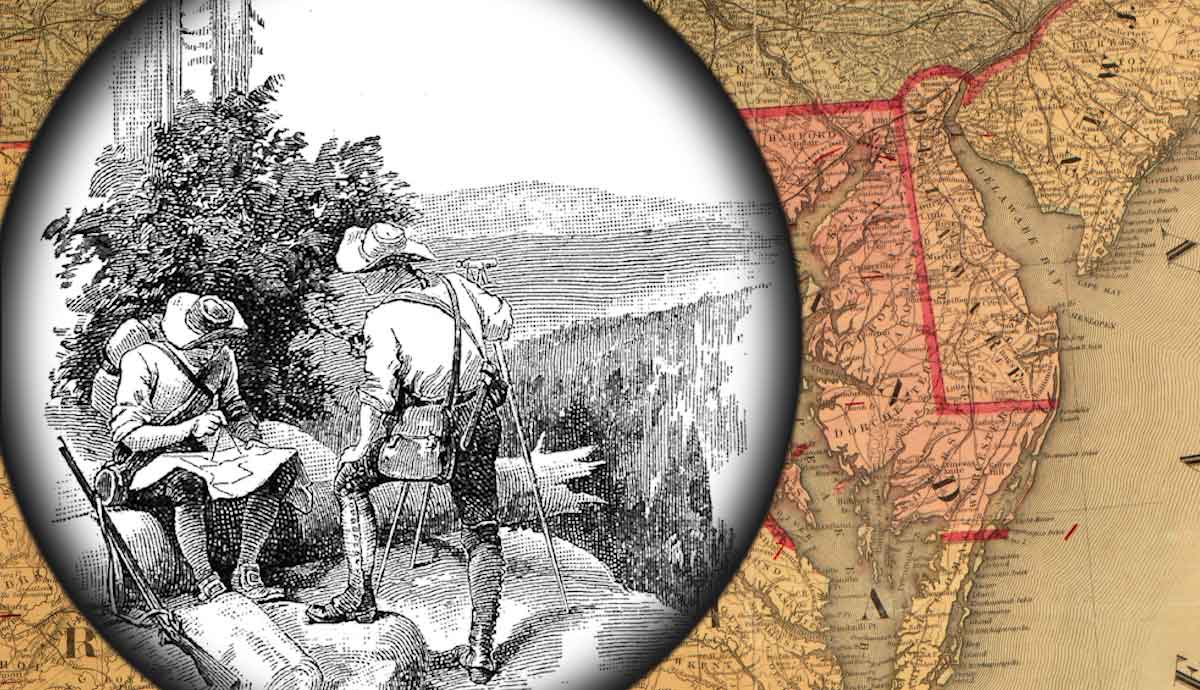

The two families hired two Englishmen, a baker’s son turned astronomer Charles Mason and outcast Quaker and surveyor Jeremiah Dixon, to survey the land and demarcate the border. Starting in April 1765, their work became the established boundaries between the Provinces of Maryland and Pennsylvania and the Colony of Delaware. It is also important to note that Mason and Dixon were not the land experts during their survey; that title belongs to the Iroquois guides who led the surveyors through the Pennsylvania and Maryland territories. The survey ended when the Iroquois refused to go any further due to hostilities with the neighboring Lenape.

In 1779, Virginia and Pennsylvania also arranged an agreement regarding the Mason-Dixon line. They wanted to establish a definitive border between the northwestern edge of Virginia and the southeastern edge of Pennsylvania. They declared that the Mason-Dixon Line would serve as this boundary indefinitely.

In 1781, Pennsylvania abolished slavery, and the Mason-Dixon Line entered a new period in history: it now demarcated the area where enslaved people were considered free. The Mason-Dixon Line not only served as a permanent boundary for the four states but also as a line that divided free states from slave states.

Where is the Mason-Dixon Line?

Mason and Dixon’s original survey finished on October 9, 1767 and began south of Philadelphia, running about 30 miles west of Pennsylvania’s southwestern corner. The line is not straight; rather, it is made up of segments of straight lines which fix the border between Maryland and Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania and Delaware, and Delaware and Maryland.

The Mason-Dixon Line runs south to north along the Delaware-Maryland border and extends 40 miles west of Maryland’s territory into Virginia. After the disputes, Pennsylvania had to come to a compromise regarding the 39th parallel, which meant the Mason-Dixon Line stopped five miles west of the Delaware river and ran straight north. The agreement, settled in 1779, demarcated a permanent boundary between Virginia and Pennsylvania and allowed both territories to keep at least some of their claimed land.

The Mason-Dixon line was resurveyed many times throughout its history, with no fundamental changes made to the original proposed by Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon. The line is physically marked by stones at every mile and “crownstones” every five miles. Crownstones were imported from England, showing an “M” on the Maryland side of the stone and a “P” on the Pennsylvania/Delaware side. The crownstones also displayed a coat of arms for each territory. While many stones have been destroyed, many remain on public land today.

How the Mason-Dixon Line Affected Antebellum & Civil War America

The term “Mason-Dixon Line” was not used until the congressional debates led to the Missouri Compromise of 1820. This bill introduced legislation defining the free northern states from the slave-holding southern states. The Missouri Compromise admitted two states to the Union simultaneously–Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state. This kept the balance between freedom and slavery equal, at least politically, for Congress. It also established, in concordance with the Mason-Dixon Line, that states and territories above the 36-degree latitudinal line could not be considered slave states. However, this line was broken 34 years later when the Dred Scott vs. Sanford decision declared the compromise unconstitutional.

In the case of Dred Scott, this decision declared enslaved people as property in the United States. In the majority reading, the Supreme Court stated that enslaved people could not be considered citizens of the United States, thereby disabling their rights and protections dictated by the Federal Government. This decision, along with the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, nullified the importance of boundaries established by the Missouri Compromise, including the Mason-Dixon Line.

However, the Mason-Dixon Line still served as an important border between the northernmost slaveholding territories of the South and the southernmost free parts of the North. After the Napoleonic Wars, Maryland planters experienced a wheat market crisis. They found they could not compete with the economy while holding fixed expenses like enslaved people. This made the symbolic waters of the Mason-Dixon Line murky. Maryland planters needed labor to compete with the market, and enslaved people wanted freedom. Wheat farming was a particularly cyclical form of work, with intense periods of labor during the harvest and a relative lack of the necessity for labor for the rest of the year. For the maximal return on their investments, Maryland enslavers held onto any form of slavery they could. Many enslavers struck a deal with their captive laborers. If the enslaved people didn’t escape over the Mason-Dixon Line, their captors would pay them for their harvest labor, and there would be no threat of selling the enslaved people into the Deep South, where the economy for slavery was incredibly profitable.

Using the Mason-Dixon Line as a bargaining chip for border state slaveholders showed the ever-growing flexibility of enslavement. In hindsight, it was a hallmark of enforced labor’s decline. This became evermore clear when South Carolina became the first state to secede from the Union in December 1860. The Mason-Dixon Line was now a political and cultural boundary and a battle line.

The Civil War is the critical point in history that cemented the concept of the Mason-Dixon Line in the collective American memory. Along the line were border states, arguably the most important in the matter of the Union and the Confederacy gaining territory. Border states could be contradictory, like Maryland, which was a part of the Union but retained slavery as law until 1864.

This was also true in Delaware, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Missouri. Border states were the area where the cultural significance of the Mason-Dixon Line came into play. Men in border states fought for both armies, and the Mason-Dixon Line was a point of contention that justified their participation in the Confederacy. To others, it necessitated their drive to join the Union.

The Mason-Dixon Line was forged into the cultural fabric of America following the Civil War, and its invisible boundary held throughout history.

The Mason-Dixon Line Today

Since the abolition of slavery in the United States, the Mason-Dixon Line has remained a significant cultural, social, and political divide between the North and the South. States like Missouri, where cities demarcated different camps during the Civil War, retain their identity as southern or northern based on this history today. Border states still have a slightly confused culture, which echoes their past as a cultural hodgepodge. Are they in the northernmost region of the South or the southernmost region of the North?

To be sure, the Mason-Dixon Line is still a helpful indicator of American politics in the modern day. Socially, it has served as a boundary throughout the 20th century; the Great Migration is the best example of this cultural change in the region. It is easy to see why, in the cultural context of the United States, the states south of the Mason-Dixon Line are generally considered to be where systemic racism comes from, while those north of the line are seen as progressive havens. This misconceived generalization continues today, stemming from the political and social divide of segregation. In the grand scheme, however, systemic racism is pervasive in the American social stratum and culture that does not discriminate based solely on the region.

Culture and politics in the United States continue to shift in the 21st century, and while both sides of the line still cling to their identity in many ways, whether through literature, politics, or popular culture, the idea that the Mason-Dixon Line serves as a fixed border of cultural significance is a moot point. At the same time, it still has importance but is not the permanent boundary for anything more than the divide between Pennsylvania and Maryland.