In the early 1820s, Mexico was a newly independent nation formed from the Viceroyalty of New Spain. Its northeastern frontier was composed of Mexican Texas and bordered the United States. Under Stephen F. Austin, emigrants from the US began to settle in this province of Texas. However, a clash of cultures quickly emerged between the American immigrants and Mexican authorities, amplified by US attempts to purchase the province from Mexico. In 1835, tensions boiled over when Mexico moved to re-militarize Texas and stop any moves toward self-rule. From October 1835 to March 1836, Texans fought for their independence in a short but brutal revolutionary war, known today as the Texas Revolution. Here’s a look at the creation of the Republic of Texas!

The 1540s: Spanish Exploration of Texas

In 1528, the first Europeans set foot in what is now Texas, landing in Galveston Bay after a hurricane destroyed their ships. They had arrived by accident: Spanish conquistador Panfilo de Narvaez had been trying to land in Florida with 400 men. Of the 80 survivors coming ashore in Texas, Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca was the highest ranking to make it back to Mexico. He returned to Spain and declared that there were riches to be found in Texas, based on the legend of Cibola: the seven cities of gold.

Four years after Cabeza de Vaca survived Texas, Francisco Vasquez de Coronado arrived in the present-day state from Mexico with 1,000 soldiers to search for Cibola. He explored the Panhandle region of West Texas but did not find gold or riches. In East Texas, fellow conquistador Hernando de Soto’s ill-fated expedition arrived in 1542, having explored much of the American South. De Soto’s successor, Luis de Moscoso de Alvarado, turned around and returned to the Mississippi River to sail back to Mexico. Neither Coronado nor Alvarado found any treasure, and Spanish interest in Texas quickly diminished.

The 1680s-1800: Spanish Settlement of Texas

The Spanish wanted little to do with Texas or the American Southwest, but knowledge of British and French exploration of North America spurred them to try to settle the area. In the 1630s, Spanish missionaries lived with Native American tribes in Texas, but the first Spanish settlement was not established until 1682, near present-day El Paso. Eight years later, the Spanish built the first settlements in East Texas to counter the French.

However, Spanish settlement was sporadic at best, with the largest settlement being San Antonio, which was founded in 1718. The province of Texas was considered to be the frontier and was far from the New Spain capital of Mexico City. As a result, there was little permanent settlement in the region, which would be an important feature leading to Texas’ successful push for independence.

1803-1819: United States Westward Expansion

While Spain allowed Texas to remain only sparsely settled, events brought a new nation, the United States, to Texas’ frontier border. In 1803, the United States purchased the large territory of Louisiana from France, which had only recently regained it from Spain, for $15 million. This created a lengthy border between the US and New Spain. Ironically, the money from the Louisiana Purchase would be used to help fund the wars of French dictator Napoleon Bonaparte, who seized control of Spain in 1808.

Spain, having fought the Peninsular War against Napoleon from 1808 to 1814, soon found itself facing wars for independence in Central and South America, including Mexico. In 1819, realizing it could not hold onto Florida as the US eyed it as a location for hostile Native Americans and escaped slaves, Spain sold the province to the United States for a $5 million assumption of damage claims. The land purchases of 1803 and 1819 reinforced many Americans’ belief in Manifest Destiny, the philosophy that the nation should expand across the North American continent from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean.

1821: Mexico Wins Independence from Spain

During the Peninsular War, Mexico seized the chance to seek independence from Spain. On September 16, 1810, the first declaration of independence was made. However, royalists based largely in Mexico City were able to quell the rebellion, forcing the revolutionaries north and into more sparsely populated territory. Many Mexicans of primarily Spanish heritage, known as criollos, wanted to retain their privileged status, which might be jeopardized in an independent Mexico.

In 1821, the Mexican War of Independence returned when revolutionary leader Vincente Guerrero joined forces with former royalist leader Augustin de Iturbide with the Plan of Iguala. This plan assured criollos that they would be socially privileged, even as much as native-born Spaniards (peninsulares) in the newly-independent Mexico. With this assurance, many criollos supported independence. On August 24, 1821, the Treaty of Cordoba granted Mexico independence from Spain.

The 1820s: Americans Begin Emigrating to Mexican Texas

In 1820, prior to Mexico’s independence, an American named Moses Austin traveled to San Antonio, the capital of Spanish Texas, to seek a land grant. After persistent negotiation, the Spanish governor finally granted him 200,000 acres for the settlement of 300 white families from the United States. However, Moses died soon afterward and the immigration venture was completed by his son, Stephen F. Austin. In December 1821, Austin brought the first American families into Mexican Texas, which eventually honored the original Spanish land grant.

Mexican Texas was sparsely populated, and the provincial governor warned Austin that there would be little government protection. The American immigrants’ desire for independence, coupled with weak oversight from the Mexican government, quickly led to moves toward self-rule. Austin received three more land grants for 300 additional families each. However, tensions between the American immigrants and the Mexican government soared when the latter abolished slavery in 1829 and then banned further immigration a year later.

Precursors to the Texas Revolution: Tensions Between Texan Immigrants & Mexico

The white American families who immigrated to Mexican Texas did not develop strong ties to Mexico. Many American immigrants were from the South and supported slavery, while Mexico largely did not. In fact, slaves escaping from the United States attempted to make it to Mexico as well as Canada during this era. Mexican Texas was largely left alone from 1821 to 1829, but the Centralist Party that took power in Mexico in 1829 sought to exert more centralized control over its northern territory. That year, Mexico also abolished slavery, prompting outrage from white slaveowners in Texas.

Although Mexico did not move immediately to enforce its stricter rules, immigrants in Texas were alarmed. In 1830, Mexico abolished immigration into its northern territory and planned to establish new forts in Texas. A new law, the Law of April 6, 1830, placed new tariffs on goods from foreign countries, including the United States. Because many Texans had close business and family ties with the United States, the tariff law increased tensions further with the government in Mexico City.

A Precursor to Independence: The Fredonian Rebellion

Tensions between white immigrants in Mexico and the Mexican government went both ways. One of several white Americans to receive land grants for settlement were Haden and Benjamin Edwards, who were allowed to bring up to 800 immigrant families into East Texas. Haden Edwards’ brash behavior quickly outraged already-established settlers, sparking feuds. When Mexican authorities learned of Edwards’ behavior, they canceled his land grant. In November 1826, Edwards and a small group of men arrested local Mexican authorities and seized a stone “fort” in Nacogdoches, Texas.

Although Edwards’ rebellion quickly fell apart, despite gaining some Native American support in exchange for promises of land, it increased suspicions of white settlers by authorities in Mexico. The authorities decided to investigate the goings-on in Texas, and General Manuel de Mier y Teran was sent to determine the situation. His expedition found that East Texas had been largely Americanized, with Americans and white Europeans outnumbering Mexicans. This information would later reinforce Mexico City’s desire for stronger control over Texas.

The Texas Revolution Begins

Tensions continued to rise after the Law of April 6, 1830. Small, localized uprisings against Mexican authorities occurred in 1830, and the Convention of 1832 aligned many Texans on concessions they desired from the Mexican government. The Convention of 1833 finalized these demands, and Stephen F. Austin was elected to bring the demands to Mexico City. Although he first succeeded in repealing the Law of April 6, 1830, Austin was arrested on his way home for allegedly inciting an insurrection.

Austin was released from prison in December 1834, having never been charged with a crime. In July 1835, he was allowed to leave Mexico City, and returned to Texas. His imprisonment made him believe that independence from Mexico was Texas’ only reasonable path, and in September he supported such a movement. Mexico was already moving to head off this movement and sent soldiers to seize an old cannon at Gonzales, Texas. On October 2, 1835, a skirmish occurred between Texas settlers and Mexican soldiers at Gonzales, with a famous flag daring the Mexicans to “come and take” the cannon. The Texas Revolution had begun!

The Texas Revolution Becomes War (1835-36)

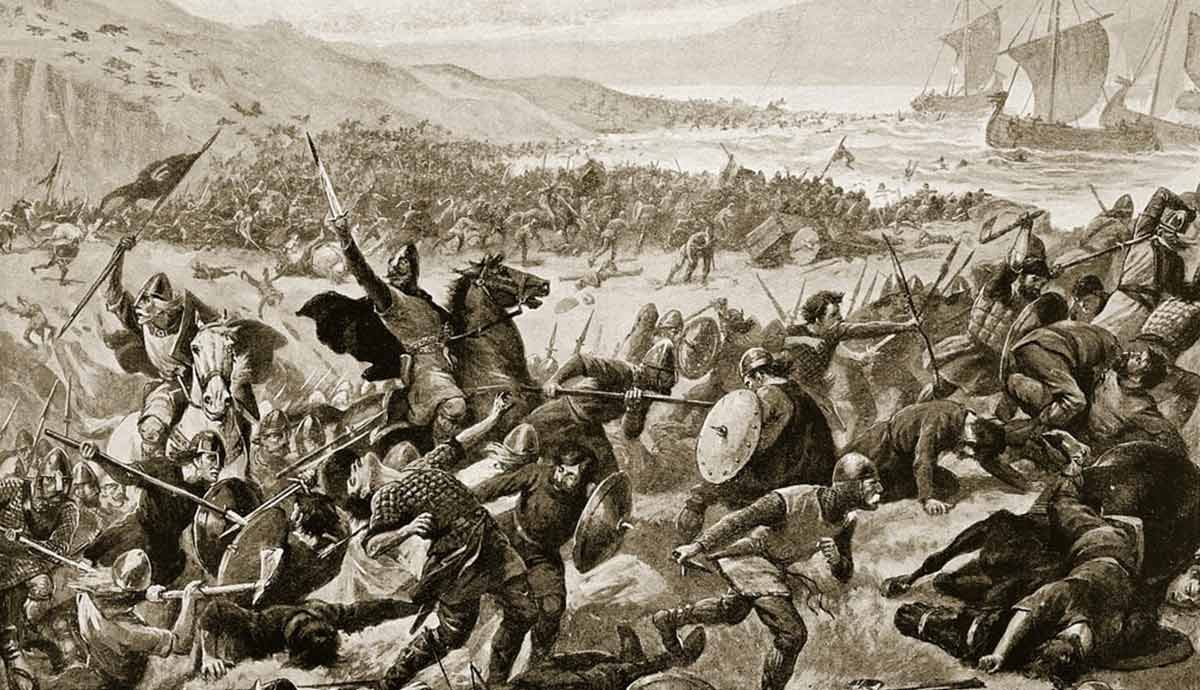

After the Battle of Gonzales, a larger Mexican force arrived at San Antonio. However, these troops had been sent prior to the events in Gonzales and were not anticipating combat. The Mexicans took defensive positions in San Antonio and were besieged by the Texian forces. This Siege of Bexar resulted in an eventual Texian victory in December 1835, giving Texans control of San Antonio. However, Mexican president Santa Anna himself arrived in early 1836 with a much larger army, leading to the historic Battle of the Alamo.

On February 24, 1836, Santa Anna’s army surrounded the Alamo mission, although some additional Texian reinforcements made it inside. After thirteen days of siege, on March 6, the battle began. A short but incredibly brutal battle saw almost all 200 or so Texian defenders at the Alamo killed. Although it was a victory for Mexico, the Alamo and the Goliad Massacre in late March only galvanized Texan (and United States) support for independence.

The Texas Revolution Leads to Independence

In terms of arms and manpower, the Texians were far outweighed by Santa Anna’s armies… but a surprise attack on April 21, 1836, changed everything. Santa Anna himself was captured in the Battle of San Jacinto and had no choice but to sign the Treaties of Velasco on May 14, which granted Texas independence from Mexico. The treaties allowed Santa Anna and his armies to leave Texas unscathed in exchange for not taking up arms against Texas again.

The new Republic of Texas encompassed more territory than the eventual State of Texas, with its western border following the Rio Grande River up into present-day Colorado. The Texas Panhandle extended north to the Arkansas River, which also extended west into Colorado. A “tail” extended north from the western edge of the Republic’s Colorado territory into present-day Wyoming. Unfortunately, this vast territory faced the same challenges it did under Spanish and Mexican rule: it was sparsely populated and difficult to defend.

1841-45: Republic of Texas Seeks Annexation

The Treaties of Velasco were not accepted by the Mexican government on the grounds that Santa Anna had signed them under duress while a prisoner. However, the Republic of Texas existed as a de facto free state and quickly pursued diplomatic recognition by other nations, including France and Britain. Faced with domestic political turmoil, as was common during the era, Mexico was not in a position to re-invade Texas in the late 1830s. Nevertheless, fears that Mexico would re-invade in the near future made many Texans desire annexation by the bordering United States to the east.

Talks about having Texas join the United States went back and forth, but a temporary Mexican re-occupation of San Antonio in March 1842 made the situation dire. Congress looked at annexation again, and in April 1844, an annexation treaty was completed and signed by representatives of the United States and the Republic of Texas. In June, this treaty was rejected by the US Senate. However, US presidential candidate James K. Polk won election on a campaign that included annexation of both Texas and Oregon. Polk’s election led Congress to hastily reconsider annexing Texas, and it agreed to the policy. On December 29, 1845, the Republic of Texas officially became the State of Texas, the 28th state to join the union. Mexico was enraged, and severed diplomatic ties with the United States, later followed by war.