The Underground Railroad is a ubiquitous term when studying the dark history of enslavement in the United States. It is a phrase that most people have heard, and most people have a vague idea of its purpose: to help enslaved African Americans escape the South. However, the actual Underground Railroad was a complex effort by people throughout the United States and Canada to assist those who sought freedom. It was a clandestine and complex network that helped enslaved people escape and rebuild their lives on the other side. This article will briefly delve into the Underground Railroad: its history, operations, leaders, and legacy.

History of the Underground Railroad

The first mention of the term “railroad” about the network of escape for enslaved peoples from the South did not appear until 1839 when an editorial by Hiram Wilson from Toronto called for the creation of “a great republican railroad … constructed from Mason and Dixon’s to the Canada line, upon which fugitives from slavery might come pouring into this province.”

While the term itself may have become mainstream in the 1840s, the system operated as the Underground Railroad had likely existed since the end of the 18th century. There is an idea in popular thought that mostly white Quakers began the Underground Railroad. Indeed, in 1786, George Washinton complained that a group of Quakers had tried to help one of the enslaved people he kept on his property escape.

While Quakers, a religious sect that believed in equality for all people, were one of the first organized groups of abolitionists, there exists the idea that Quakers and white abolitionists were solely responsible for transporting helpless freedom seekers, shepherding them graciously northward. This, however, was not the case. Henry Louis Gates Jr. states that this idea probably came from the study of Wilbur Siebert in 1898. Siebert interviewed many Underground Railroad collaborators who were still alive in the 1890s. He seems to emphasize, Gates claims, the white conductors while leaving formerly enslaved people out of the narrative of their agency in escaping enslavement.

However, as Gates says, the Underground Railroad was mainly conceived and operated by free northern African Americans, especially at its inception. Quaker abolitionists, on the other hand, set up early groups to aid enslaved peoples in their attempted escapes. This includes groups of Quakers in North Carolina who helped establish routes and stations for escapees. One of the men known for operating the Underground Railroad in these early days was Philadelphian William Still, who also accepted Quakers’ help in his mission. Still recorded the rescue of some 650 freedom seekers whom he sheltered in Philadelphia. Along with individuals like Still, the African Methodist Episcopal Church was also a very active group in the operations of the Railroad.

While the Fugitive Slave Act was introduced in 1793, the expansion of the Railroad would not occur until after 1850, when the Act was updated to make the punishment for assisting escaped enslaved people harsher. One could be charged with “constructive treason” for aiding African Americans in their bids for freedom, so it was not necessarily a popular cause that people, even in the North, took up. Furthermore, the rewards posted for catching freedom seekers were often a hefty sum, which motivated many people more than their morals did.

How the Underground Railroad Functioned

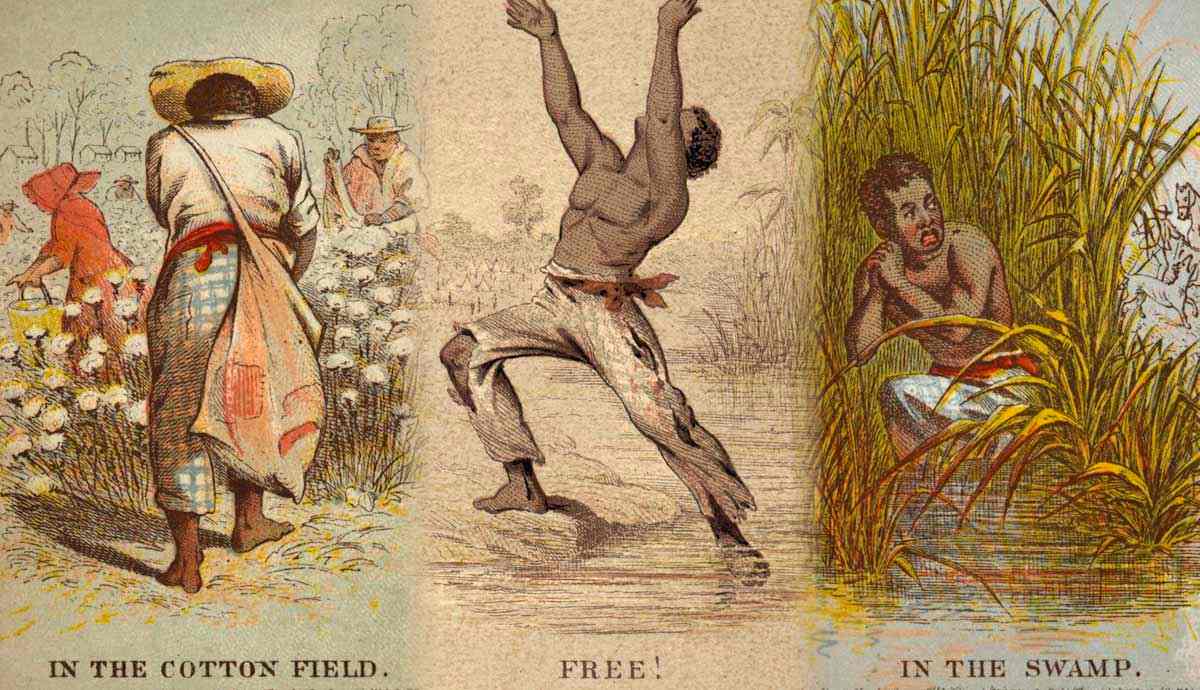

The Underground Railroad, despite its name, was not a line that ran uniformly from the South to the North, quickly taking freedom seekers on their way. The Underground Railroad primarily operated in the North, meaning that escapees would be on their own from the plantation to the crossing of the Ohio River or the Mason-Dixon Line. Once they trekked into a free state, an escapee would gain more assistance.

The Underground Railroad was set up as a series of stops in free states and some in the South that led to a destination where the escaped enslaved person could settle. The people who assisted those fleeing were called “conductors.” Many believe that enslaved people had songs to warn of a time to escape or to inform the other enslaved people that a conductor was coming. Another common myth is that enslaved people fashioned “freedom quilts,” which cryptically held a map to freedom from within the patterns on the quilt. These stories are fictitious; as Gates states, enslaved people could not risk exposing an attempted escape by a supposedly cryptic message in a song or a pattern in a quilt that they would have instead used to keep warm.

The enslaved people who escaped did so with a general idea of where they were going. While the songs of lore may not have existed, the grapevine did. The grapevine telegraph line was a communication system that interconnected many plantations in the American South through mobile enslaved men passing messages to one another. This not only allowed enslaved people to learn about news from other plantations but also to glean both geographical information and information regarding abolitionist groups and their locations.

Around 80 percent of those who used the Underground Railroad were individual men. Since the grapevine was mainly based around enslaved males, this was the majority of the population that escaped. Families sometimes fled together, but women often feared that their child-rearing duties and housework would be missed too easily to allow them ample time to escape.

Once an enslaved person decided to escape, they did so by themselves until they encountered a conductor who assisted them in sheltering in houses, churches, and schoolhouses. These shelters along the way to safety were called “stations,” “safe houses,” or “depots.” Those who ran the stops were called “stationmasters.” Eventually, an escapee would make it to safer territory, whether a free state in the far North or, after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, Canada, Mexico, or the Western United States.

Station-Masters & Conductors: A Few of their Stories

Both white and Black people served as conductors and station masters for the Underground Railroad. While famous names stand out in history textbooks, most people who helped the Underground Railroad operate were ordinary people: ministers, farmers, and business owners. We are familiar with a few today: Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, and John Brown being prime examples of the Underground Railroad in the collective American memory.

A free Black man and foundry owner named John Parker risked his own life by infiltrating plantations in Kentucky and ferrying the enslaved people to freedom across the Ohio River. Robert Purvis, an escapee turned merchant, formed a Vigilance Committee in Philadelphia in 1838. Another formerly enslaved man, Josiah Henson, created the Dawn Institute in Ontario to help escapees learn new trades they would need to work in Canada. These people, seemingly ordinary freedmen, each helped piece together the moving parts of the Underground Railroad. Men and women like them made the network successful.

A few conductors and station masters were not standard, but today they are not the names that spring to mind when one considers the operations of the Underground Railroad. This includes Gerrit Smith, financier, the only avowed abolitionist to run for president (three times), and longtime acquaintance of Frederick Douglass, who helped large swaths of enslaved people escape, both through direct and indirect channels. Smith was implicated in John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia, for financing the mission on Brown’s behalf. Though he denied any knowledge of the raid specifics, he was likely well aware of Brown’s plans.

Smith contributed to social justice for African Americans in many ways, and in 1841, he even bought an entire family of enslaved people from Kentucky to set them free. He was a close confidant of Frederick Douglass and advocated for Black men to receive the right to vote. He donated land to escaped people, and his contributions to social justice raised $8 million throughout his lifetime. Though Smith was not necessarily a conductor, he did move the mission of the Underground Railroad along through financial support, a sort of Railroad supervisor.

One man who began serving as a conductor at the age of 15 and later as a stationmaster was Levi Coffin. Born a Quaker in North Carolina, Coffin was a staunch believer in the amorality of slavery and began assisting escapees with the help of his family at a very young age. Coffin eventually moved to Indiana, where his home was often called the “Grand Central Station of the Underground Railroad.” After moving to Cincinnati, Ohio, Coffin ran a produce store that only sold items produced with free labor, raising over $100,000 for the Western Freedmen’s Aid Society, which helped provide escapees with food, clothing, and shelter. He assisted over 2,000 escapees in 20 years. Levi Coffin retired after the passage of the 15th amendment and spent the rest of his life writing memoirs.

Samuel Burris was born a free Black man in Delaware. He worked for his entire life, first as a laborer and farmer, then as a well-respected teacher. Burris and his family moved to Pennsylvania after the laws in Delaware began to constrict the liberties afforded to freedmen and women. He joined the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society and served as a conductor on the Underground Railroad, helping to smuggle people from Maryland and Delaware into Pennsylvania.

During one such mission, Burris was caught attempting to help a woman board a steamship from Maryland. His white co-conspirators were given fines, while Burris was sentenced to a little over a year in prison, $500 in fines, and 14 years of enslavement following his release from jail. Luckily, a Quaker abolitionist, Isaac Flint, was inserted as a buyer at the auction for Burris, and Flint purchased Burris to return him to freedom. Burris continued working as an Underground Railroad agent until, under threats of danger to his family, he moved to San Francisco, where he continued his promotion of rights for African Americans until his death.

The End of the Line & the Legacy of the Underground Railroad

Ultimately, the number of enslaved people ushered to freedom through the Underground Railroad was not significant enough to collapse the entire institution of slavery. Gates estimates that a range between 25,000 and 50,000 people escaped slavery through the Underground Railroad before the Civil War.

In 1860, while there were almost 490,000 free Black Americans, there were still 3.9 million enslaved Black Americans. As Gates points out, the number of freedmen and women in 1850 was about 430,000. While this increase can be partially attributed to escapes, it is still dwarfed by the number of people in bondage at the beginning of the Civil War. Many enslaved people ran away within the South, never reaching free states. If the Underground Railroad had been wildly successful, the collapse of the Southern economy would have meant that there was probably no need for secession or Civil War. Unfortunately, as we know, that was not the case.

The Underground Railroad may not have toppled slavery, but it still lives on in our collective memory as a triumph of the abolitionist cause before the Civil War. The decision to escape would not have been taken lightly by enslaved African Americans, and those who did decide to do it should be celebrated. However, it is essential to note that those African Americans who couldn’t escape were not cowards. They were simply afraid, and understandably so, as many who tried did not succeed. Enslavement, as we understand it today, was wrong. We should honor those who escaped bondage and those who never had the opportunity.