For most of British history large open fields were divided into scattered strips of land and farmed by peasant cultivators. By the Tudor period common land was being ‘enclosed’, or hedged and fenced off from the local peasantry. After 1750, parliamentary enclosure acts became the preferred method for transforming common land into private property. Land tilled or grazed by the peasant farmers was put to more profitable use, to the great benefit of landowners. Meanwhile, the agricultural population was forced to leave the land and seek work in the towns and cities.

Early Enclosures

Prior to 1750, when enclosure by Parliamentary act became standard practice, substantial transformations were already underway. The earliest enclosures date to the Tudor period (1485-1603) and were driven on the one hand by the desire of the crown to gain the support of noble families, and on the other, increasing demand for wool. The open field system was the focus of attack, as manorial lords looked to enclose common land and convert it into sheep pasture. Wool, the cornerstone of England’s export trade, was a highly lucrative enterprise.

Early enclosures were ‘informal’ agreements and more often than not backed by violence. At times ‘closes’ (small fields or paddocks) were created by partitioning open fields. In other instances, entire parishes were enclosed with ruthless disregard for the rights of small farmers and villagers.

Tudor Riots and Rebellions

The denial of customary rights of pasture and enclosure of common land often led to what historians have called “enclosure riots.” These riots varied in their intensity. Local village revolts typically involved small-scale actions, such as the tearing down of enclosure fences and levelling of hedges to allow their cattle access.

However, on some occasions, village disturbances turned into large-scale rebellions, like Ket’s rebellion of 1549, which culminated in the capture of the city of Norwich. Similarly, the Midland Revolt of 1607, led by “Captain pouch,” began with a mass protest against enclosure, focusing on the destruction of hedges and filling of ditches. Whether it was a village revolt or a large-scale rebellion, the underlying motivation behind enclosure riots was to symbolically restore the rural customary rights that greedy landlords had turned “upside down”.

Enclosure by Act

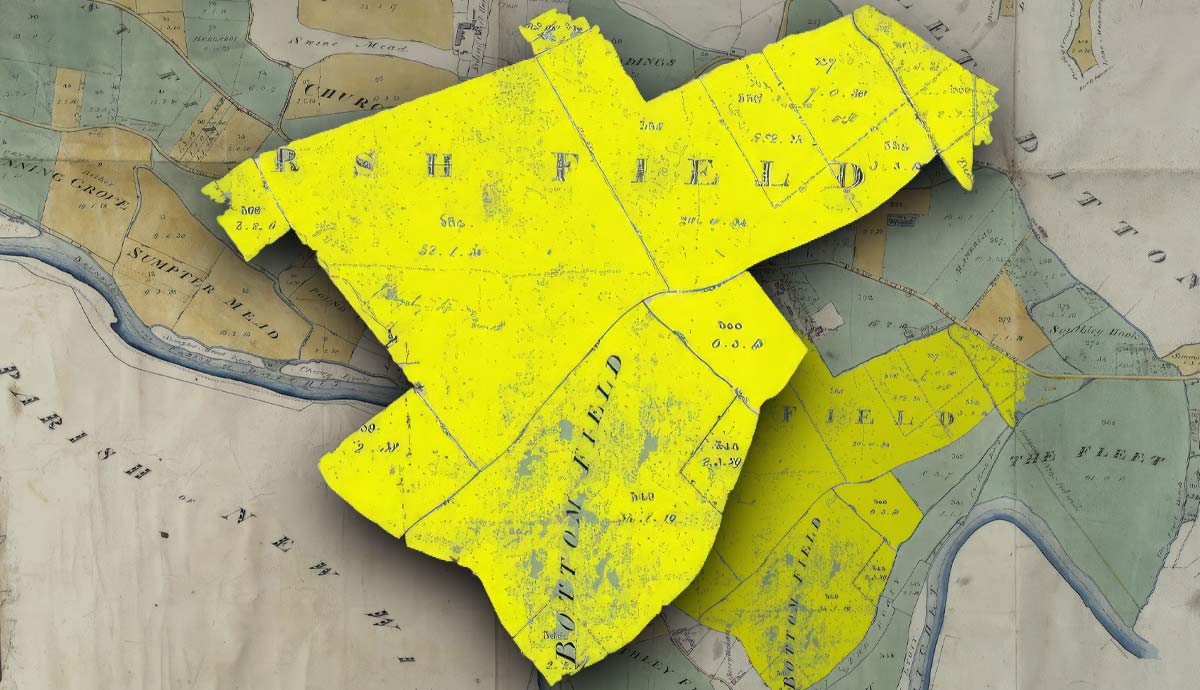

Parliament eventually assumed control of the business of enclosure in the seventeenth century. However, while the first Act of enclosure by parliament was in 1604, it wasn’t until after 1750 that parliamentary enclosure really gained momentum. This later round of enclosures was far more structured that the Tudor version of events. Typically, parliamentary enclosures were initiated by several – or even one – prominent landlord by way of a petition to parliament. Subsequently, there was an opportunity for objections to be heard, following which a decision was reached to approve or reject the petition.

In theory, there was a framework to hear objections, but in practice the substantial influence wielded by landlords heavily swayed outcomes. Accordingly to parliamentary figures, between 1604 and 1914, over 5,200 enclosure bills were filled, effecting some 6.8 million acres of land.

Enclosure Was the Bedrock of the Industrial Revolution

The industrial revolution was closely intertwined with enclosure and the subsequent revolution in agriculture. Accordingly, the remnants of the open field system that characterized agriculture in the British Isles for most of its history that survived the Tudors, was relentlessly dismantled by the Parliamentary enclosure acts.

In the eighteenth century, agriculture was still a large part of the British economy, and the increasingly powerful landowning classes were resolute in their ambition. Land, they believed, should not be allowed to lay idle – it must be put to work and used efficiently. In the context of increases in food and wool prices they looked towards aggressive enclosure. Thus, armed with the powers of parliament, and in the name of efficiency and the elimination of idleness, Britain’s agricultural revolution got under way. Unsurprisingly , when the government published an 1873 report on land ownership, it revealed that almost all of the top 100 landowners were also members of the House of Lords.

The Acts Were Surrounded by Controversy and Tragedy

Controversy still surrounds the enclosure acts. Were they a necessary step in the modernization of British agriculture and development of the national economy? Or did they represent a ruthless seizure of land and deprivation of the rural poor of their rights to the land? As Karl Marx saw it, the enclosures in England amounted to a “systematic theft of communal property.” He argued that they served two primary purposes: first, to kickstart capitalist agriculture, and second, to “set free the agricultural population as a proletariat for the needs of industry.”

In the realm of literature, Romantic poetry lamented the disconnection from nature brought about by enclosure. The disappearance of common land and small farms gave rise to large cities as the new norm for people living in England. For better or worse, the enclosure acts wrought profound transformations on both the British landscape and the culture and composition of rural society.