Linear perspective – or lines which converge into one or more distant vanishing points – is one of the art world’s most ingenious discoveries. Throughout the centuries, artists have explored how this mathematical hack can create the illusion of infinite space and make interior and exterior buildings appear to recede into the distance. But who actually discovered linear perspective? Attempts to create spatial depth in art have been in existence since ancient Greek and Roman times. But it was the Renaissance architect and artist Filippo Brunelleschi who made the first mathematical drawing using linear perspective, and his discoveries had a phenomenal impact on the history of art.

The Architect Filippo Brunelleschi Devised Linear Perspective

The Renaissance architect Filippo Brunelleschi made the first known drawing in 1415 that used the mathematical system of linear perspective to create the illusion of a building receding towards the horizon line. But he wasn’t the first to make an attempt at doing so – in fact, Greeks and Roman used angular lines to convey space in their art. Centuries later, both early Renaissance artists Giotto di Bondone and Duccio di Buoninsegna both used similar devices. But it was Brunelleschi who made the most radical breakthrough. He devised a simple and easy to apply system of creating a vanishing point on a horizon line and drawing diagonal lines towards it. These diagonal lines could convey roads, buildings or interior spaces vanishing into the distance. Brunelleschi also observed through his use of linear perspective that forms and spaces appeared smaller when further from the eye.

Leon Battista Alberti Documented Brunelleschi’s Linear Perspective

The Renaissance architect, writer and all-round polymath Leon Battista Alberti took Brunelleschi’s incredible discovery and recorded it in his treatise Della Pictura (On Painting) in 1435. Alberti was the first European to write such a theoretical text about making art. He argued that perspective was a powerful tool that linked art with the rising humanist interest in scientific and mathematical reason. Alberti wrote, “Know that a painted thing can never appear truthful where there is not a definite distance for seeing it.”

Raphael and The School of Athens

Italian Renaissance artists began applying the principles of linear perspective into their art from the 1420s onwards. Raphael’s masterwork titled The School of Athens, 1509-11, is one of the finest examples of linear perspective at play, and the incredible, awe-inducing qualities of depth and space artists were able to create while using this mathematical system. Other notable artworks which would not have been possible without perspective include Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper, 1494-98, and Pietro Perugino’s Delivery of the Keys to Saint Peter, 1481-2. If you look closely enough, in some Renaissance masterpieces, more than 20 horizontal lines can be traced back to a single vanishing point!

Two and Three Point Linear Perspective

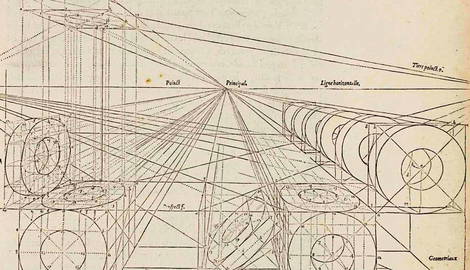

Two and three-point perspectives came later, most notably through the writer Jean Pelerin, known by the name ‘Viator.’ In his De Artificiali Perspectiva, 1505, he wrote about using a further two ‘tier points’ alongside the central vanishing point, which enabled artists to depict buildings seen from a series of unusual or oblique angles.

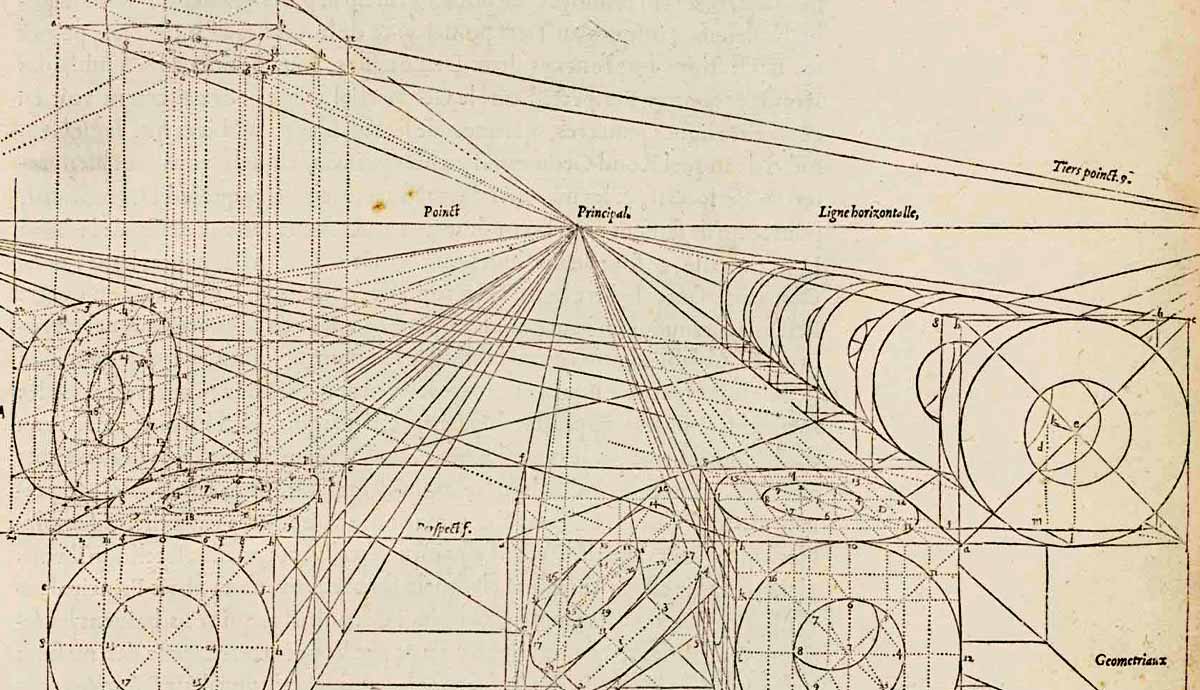

Later, building on all this history, the perspective theorist Jean Cousin perfected Pelerin’s ‘tier point’ theory, and added to it a series of accurate methods for foreshortening the human body in Livre de Perspective, 1560. By 1600, it was largely expected that artists should have a firm understanding of perspective in order to be taken seriously by their patrons. Since then, artists and theorists continued to add multiple perspective points into their optical experiments. Many of these discoveries continue to prove hugely popular, and even vitally important, across the fields of art and design today.