Traditionally, scholars have viewed Charles Parham as the father of the Pentecostal Movement. However, the increase in decolonized perspectives on subjects of academic study has resulted in a re-investigation of the matter.

In the last couple of decades, several scholars have argued that William Seymour, rather than Charles Parham, should be credited with the title “Father of Pentecostalism.” Yet, a closer investigation shows that more than just contemporary narratives are at play. Both Charles Parham and William Seymour’s claims to be the father of the fastest-growing movement in Christianity in the 20th century are doubtful. The foundations for such objections are theological, not just social-political.

The Argument in Favor of Charles Parham

On the 1st of January 1901, Charles Parham laid hands on Agnes Ozman at the Bethel Bible College in Topeka, Kansas. She began speaking in tongues and wrote in what some claimed to be Chinese. Soon afterward, some other students at Parham’s school had similar experiences. Parham himself soon spoke in tongues as well.

When interviewed by news media, Parham told the journalists that this manifestation of speaking in tongues was the same as the event that happened on Pentecost. The Holy Spirit enabled people to speak languages they had not learned. Parham believed that this ability would empower people to evangelize among groups that spoke the languages the evangelists received. It would also indicate in which part of the world the evangelist was supposed to serve. Parham taught that the gift of speaking in tongues was evidence of “Spirit baptism.”

It is clear from newspaper articles that many people were skeptical of this new manifestation. Others believed in the message of a new Pentecost that Parham proclaimed. There is no evidence that the people who spoke in tongues spoke actual foreign languages. When missionaries returned from their missions in other countries, they admitted that they could not miraculously speak the languages of the people they aimed to reach. They had to learn the languages by studying their vocabulary and grammar. Parham, however, persisted in proclaiming that the people who spoke in tongues spoke foreign languages.

Almost all scholars of church history trace the origins of the later Pentecostal Movement to Charles Parham and the tongues-manifestations at Topeka, Kansas. They also recognize that Parham is the originator of the belief that speaking in tongues is evidence of Spirit baptism.

The Argument in Favor of William Seymour

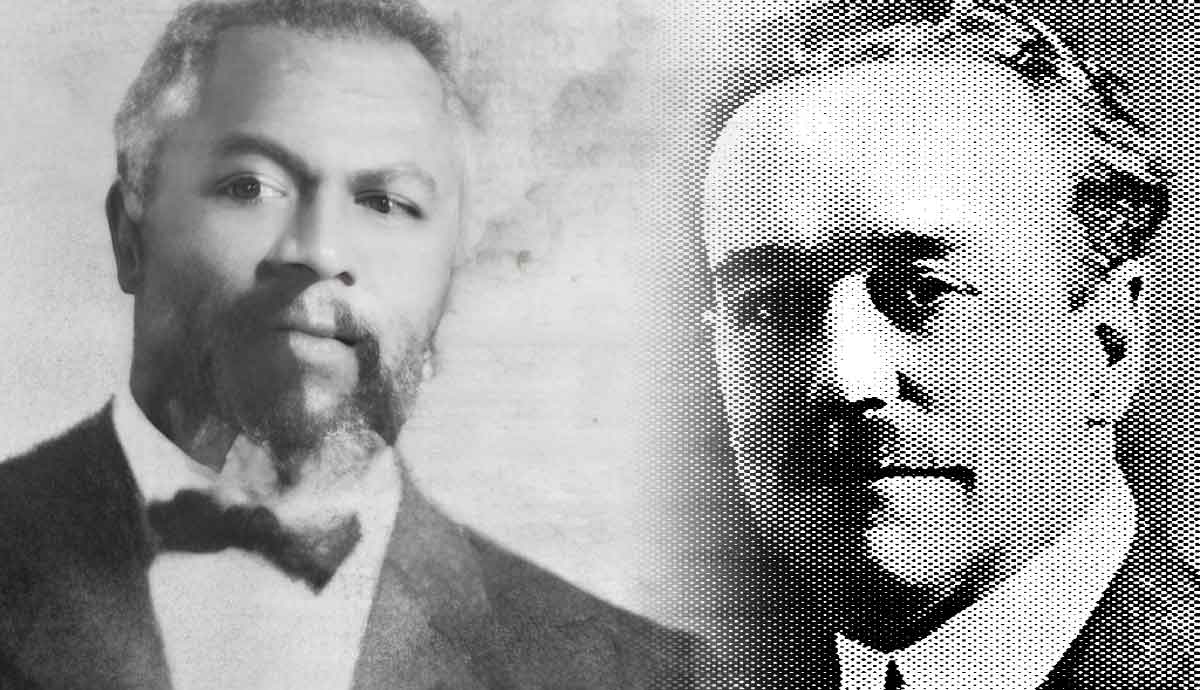

Parham moved away from Stone’s Folly, the building his ministry used in Topeka, and later settled in Houston, Texas. He established a school there, like the one in Kansas. Among his students was an African American man named William Seymour. Seymour, who happened to be blind in one eye, came from humble origins but had a passion for spreading the Gospel. He learned that tongues provided the initial evidence of Spirit baptism from Parham, though he did not experience speaking in tongues himself at that stage.

A lady who visited the Houston area and heard Seymour speak invited him to minister in Los Angeles. In Los Angeles, Seymour preached the message of tongues as the initial evidence of Spirit baptism, but the leaders of the congregation he started preaching to, opposed his teaching and closed their doors to his ministry. Some attendees, however, accepted his teaching and opened their houses to him so he could preach there.

The manifestation of tongues supposedly followed soon after, and attendance increased rapidly. A larger facility was required, and Seymour established the Azusa Street Mission. Here, many more people spoke in tongues. The word about what was happening at the Azusa Street Mission soon spread across America and Europe.

Soon, people from all over the nation and the world came to listen to the message preached at the Azusa Street Mission. Many joined in the experience of speaking in tongues. They took the message with them when they returned to their native countries. What came to be known as the Pentecostal Movement soon spread all over the world.

The Parham-Seymour Conflict

Seymour felt overwhelmed by the exponential growth of his ministry. In 1901, Seymour wrote a letter to Parham. In it, he expressed concerns about some of the manifestations that accompanied speaking in tongues. It included but was not limited to shaking, screaming, fainting, and falling over. He asked his mentor, Parham, to visit the Azusa Street Mission and provide guidance on the manifestations that occurred there. It seems he wanted Parham to take charge and bring things to order. The Apostolic Faith, a newsletter of the Azusa Street Mission, recognized that Parham’s ministry was the origin of what they were teaching. It advertised that Parham would soon visit and minister at their facilities on Azusa Street.

After some delay, Parham visited Azusa Street and almost immediately opposed what he encountered there. He stated that the manifestation of speaking in tongues at the Azusa Street Mission was not biblical. It was babbling and essentially unintelligible speech (referred to as glossolalia), in contrast to speaking in another language (referred to as xenolalia). He accused some of the leadership at the Azusa Street Mission of hypnotizing their attendees.

Parham also opposed the multi-racial services and objected to men and women falling on and over one another when they worshiped. He found it particularly objectionable when the men and women were from different races. The leadership, including Seymour, rejected Parham’s warnings and continued without him. Parham was effectively rejected by the Azusa Street Mission’s leadership. The change in Parham’s status was noted and mocked by detractors of the fledgling movement.

Parham arranged events in Los Angeles where he preached against the manifestations at the Azusa Street Mission, but he did not gain significant traction and soon left California. The Azusa Street Mission and its teaching were the primary impetus for the worldwide Pentecostal Movement.

Objections to Charles Parham

Several objections come to mind against Parham as a potential father of Pentecostalism. Firstly, Parham was known for belittling black Pentecostals and using racist language. He was friendly with the Ku Klux Klan and practiced segregation. He did not allow William Seymour to sit with the white students in class. Seymour had to sit outside and listen to lectures through an open window or door.

After Parham left California, charges of sodomy with a Jewish boy were laid against him in San Antonio, Texas, in July 1907. Parham, a married man, suffered significant reputational damage even though this case never went to trial. In part, it was because it was not the first or only sex-related claim made against Parham. A disciplinary hearing found Parham guilty of making inappropriate sexual advances on a member of the Apostolic Faith in League City, Texas, in April 1907.

Parham believed that the tongues spoken in his school in Topeka and throughout the rest of his ministry were foreign languages. However, the evidence suggests that it was nothing other than unintelligible language, no different from the Azusa Street Mission manifestations. Parham ignored any criticism and evidence contrary to his view. He held fast to the teaching that tongues empowered missionaries to speak to foreign nations in their native language, even when returning missionaries testified to the contrary.

Objections to William Seymour

Seymour freely acknowledged Parham as his mentor and called on him for assistance when he faced challenges in the Azusa Street Mission in Los Angeles. In the Apostolic Faith newsletter, on more than one occasion, the Azusa Street Mission acknowledged that it traces its origins back to Parham’s ministry in Topeka, Kansas. Seymour was not the originator of the teaching that tongues serve as the initial evidence of Spirit baptism.

The major challenge comes from Seymour’s view on tongues as evidence of Spirit baptism. It is a central tenet of Pentecostalism. A couple of months after the rift between Parham and Seymour, the latter seems to have changed his view on tongues as evidence of Spirit baptism. Seymour became convinced that the fruits of the Spirit, rather than speaking in tongues, were unequivocal evidence that the individual was baptized in the Holy Spirit. If he opposed such a central pillar of Pentecostalism, could he legitimately be considered its father?

Conclusion

Scholars have traditionally seen Charles Parham as the father of the Pentecostal Movement. His open opposition to glossolalia as a legitimate manifestation of speaking in tongues does, however, eliminate him as a contender for the father of Pentecostalism. How can the father of a movement be fundamentally opposed to the manifestation the movement is most known for?

Scholars attribute the major growth and worldwide spread of Pentecostalism to William Seymour’s ministry at the Azusa Street Mission in Los Angeles in 1906 and afterward. He was, however, not the originator of the teaching of tongues as the initial evidence of Spirit baptism. This teaching is central to Pentecostalism. Seymour went as far as to reject this teaching mere months after the rift between him and Charles Parham.