Malik Ambar began life under grim circumstances. Sold into slavery by his own parents, he would change hands again and again until he arrived in India – the land where he would find his destiny. The death of his master freed Ambar, and he immediately set out to make his mark by gathering an army of locals and other Africans as mercenaries.

From there, Ambar’s star would rise quickly. He would come to be master of the rich land he had once served, only to serve it with more devotion than ever. He defied the great Mughal Empire so brilliantly that no Mughal would get past the Deccan- until he died in 1626.

Leaving Africa: Chapu Becomes Malik Ambar

Malik Ambar began life in 1548 as Chapu, a young Ethiopian boy from the pagan region of Harar. Though we know little of his childhood, one may imagine Chapu, already an uncommonly bright boy, carefree and scaling the rugged dry hills of his native land – a skill that would help him later in life. But not all was well. The extremities of poverty hit his parents so hard that they were forced to sell their own son into slavery to survive.

His life for the next few years would be full of hardship. He would be continually transported across the Indian Ocean in miserable dhows, changing hands at least thrice amongst a chain of Indian Ocean slave traders. Along the way, he would be converted to Islam- so that young Chapu became grim “Ambar”- Arabic for amber, the brown Jewel.

Things changed when Ambar arrived in Baghdad. Mir Qasim al-Baghdadi, the merchant who bought him, recognized a spark within Ambar. Rather than relegating the young man to menial work, he decided to educate him. His time at Baghdad would be instrumental to Ambar’s future successes.

India: The Slave Becomes the “Master”

In 1575, Mir Qasim arrived in India on a trading expedition, bringing Ambar with him. Here he caught the eye of Chingiz Khan, the prime minister of the Deccan state of Ahmednagar, who would buy him. But Chingiz Khan was not just any Indian noble- in fact, he was an Ethiopian like Ambar.

Medieval Deccan was a land of promise. The riches of the region and the struggle to control had given it a unique atmosphere of martial meritocracy, where anyone could rise far beyond their stations. Many Siddis (former African slaves) had become generals or noblemen before Chingiz and Ambar, and many more still would do so after them. The living proof of this incredible social mobility in his new master must have come as a welcome surprise to Ambar, who soon began to distinguish himself. Chingiz Khan would eventually come to see Ambar almost as a son, who would learn valuable new skills of statecraft and generalship in his service.

When Chingiz died in the 1580s, Ambar was finally his own man, and an incredibly resourceful one at that. In short order, he managed to gather other Africans as well as Arabs to form a mercenary company. Ambar left Ahmednagar with his men and for a while worked for hire all over the Deccan. His motley band had grown to a 1500 strong army under capable leadership. Ambar was awarded the title of “Malik” – lord or master – for his military and administrative acumen. In the 1590s, he would return to Ahmednagar where a new threat had emerged – The Mughal Empire.

Chand Bibi and Mughal Incursions

Though we are for now only concerned with Ambar, the scope of Deccani social mobility went beyond just ex-slaves. Chand Bibi was an Ahmednagari princess. She was married off to the Sultan of neighboring Bijapur, but the marriage would prove quite short. Her husband died in 1580, leaving Chand Bibi as regent for the new boy king. While Ambar was off gallivanting across the Deccan, she negotiated treacherous court politics in Bijapur- including an attempted coup by Ikhlas Khan, another Siddi noble.

Somehow she managed to stabilize the situation in Bijapur and returned to Ahmednagar, where her brother the Sultan had died. She again found the mantle of state thrust upon her, in her infant nephew’s stead. But not all were content with this state of affairs. The minister Miyan Manju schemed to set up a puppet ruler to rule Ahmednagar for himself. When faced with opposition, he did something that he would soon come to regret.

On Manju’s invitation, the armies of the Mughal empire came pouring into the Deccan in 1595. He at long last realized what he had done and fled abroad, leaving Ahmednagar to Chand Bibi and with it the unenviable privilege of facing imperial might. She immediately sprung into action, leading a heroic defense from horseback to repulse the invaders.

But the Mughal attacks did not stop. Despite gathering a coalition of Bijapur and other Deccani forces (likely including Ambar’s men), defeat would eventually come in 1597. By 1599, the situation was dire. Treacherous nobles managed to convince a mob that Chand Bibi was at fault, and the brave warrior queen was murdered by her own men. Soon afterward, the Mughals would capture Ahmednagar and the Sultan.

Exile and the Marathas

Although Ahmednagar proper was now under Mughal hegemony, many nobles continued their resistance from the hinterland. Among them was Malik Ambar, by now a veteran of countless battles, hardened in the Deccani hills. Ambar continued to gain strength in exile, partly owing to an increasing number of Ethiopians arriving in the Deccan. But increasingly, he began to rely on more local talent.

A homebred warrior people, it is rather curious that the Marathas would have to be “discovered” by an outsider. Extremely deadly as light cavalry, they had perfected the art of harassing enemy troops and destroying their supply lines. Though the Sultanates had recently begun employing these expert horsemen, it was only under Malik Ambar that their true potential was revealed.

Ambar and the Marathas must have found something of themselves in each other; both were people of the hills, struggling with the harsh environment as much as with invaders. Ambar would come to command just as much loyalty in the Marathas as he did in his fellow Ethiopians. In turn, he would use the Maratha’s mobility and knowledge of the local terrain to devastating effect against the Mughal Empire, as the Marathas themselves would much later.

Rise of Malik Ambar, the Kingmaker

By 1600, Malik Ambar had managed to fill the power vacuum left after the Mughal imprisonment of the Ahmednagari Sultan, ruling in all but name. But that last veneer had to be maintained, as the proud nobility would never accept an African king. The astute Abyssinian understood this and so pulled off a brilliant political maneuver.

He managed to find the sole left heir to Ahmednagar in the remote city of Paranda. He proceeded to crown him Murtaza Nizam Shah II of Ahmednagar, a weak puppet through which to rule. When the Bijapuri sultan expressed doubts, he married his own daughter to the boy, thus both reassuring Bijapur and binding his puppet Sultan even closer to himself. He would promptly be appointed Prime Minister of Ahmednagar.

But troubles were far from over for Ambar. Over the treacherous decade, he had to balance, on the one hand, the belligerent Mughals and, on the other hand, domestic troubles. In 1603, he faced a rebellion by discontent generals and made a truce with the Mughals to focus on the new problem. The rebellion was crushed, but Murtaza, the puppet ruler, saw that Ambar too had enemies.

In 1610, Malik Ambar was again the target of court intrigue. The Sultan saw his opportunity and conspired to get rid of Malik Ambar. But Ambar learned of the plot from his daughter. He had the conspirators poisoned before they could act. Then he put the 5-year-old son of Murtaza on the throne, who naturally made a much more compliant puppet.

Beyond Warfare: Administration and Aurangabad

Having secured the domestic front, Malik Ambar went on the offensive. By 1611, he had recaptured the old capital of Ahmednagar and pushed the Mughals back to the original frontier. This meant vital breathing room, and Ambar used it wisely by maintaining over 40 forts to act as bulwarks against the Mughal Empire.

He then built his new capital, right at the Mughal border – Khadki, or Aurangabad as it is known today. From its multicultural citizenry and striking monuments to its sturdy walls, Khadki was perhaps the greatest symbol of its creator’s life and ambitions. Within just a decade, the city grew into a bustling metropolis. But its most remarkable feature wasn’t the palaces or walls, but the Neher.

The Neher resulted from a lifetime spent in pursuit of water. Whether in famished Ethiopia, Baghdadi deserts, or evading Mughals in dry Deccani highlands, an acute lack of water had shaped Ambar’s experiences. He had gained the ability to find water in the unlikeliest of places. Previously, Ambar had experimented with designing water supply for Daulatabad. Although Ambar abandoned that city like Tughluq before him, this experience further honed his urban planning skills.

His grand plans were treated with scorn, but through sheer determination, Ambar managed it. Through an intricate network of aqueducts, canals, and reservoirs, he managed to supply the needs of a city of hundreds of thousands, transforming the lives of the Ahmednagar citizens. The Neher survives to this day.

Besides his capital, Ambar embarked on several other projects. Relative peace meant that commerce flowed freely across the land. This and his administrative reforms allowed him to become a great patron of art and culture. Dozens of new palaces, mosques, and infrastructure were built, bringing prestige and prosperity to Ahmednagar. But all good things must come to an end. Inevitably, the truce with the Mughals was broken.

The Bane of the Mughal Empire

Sometime around 1615, hostilities resumed between Ahmednagar and the Mughal Empire. Being by far the underdog, Ambar had to rely on his tactical brilliance to beat his superior foe. Regarded as the pioneer of guerilla warfare in the Deccan, Ambar confounded the Mughals who were used to straightforward battles. Ambar would lure the enemy into his territory. Then, with his Maratha raiders, he would destroy their supply lines. In the harsh Deccan, the large Mughal armies could not live off the land in the unforgiving Deccan – in effect, Ambar turned their numbers against them.

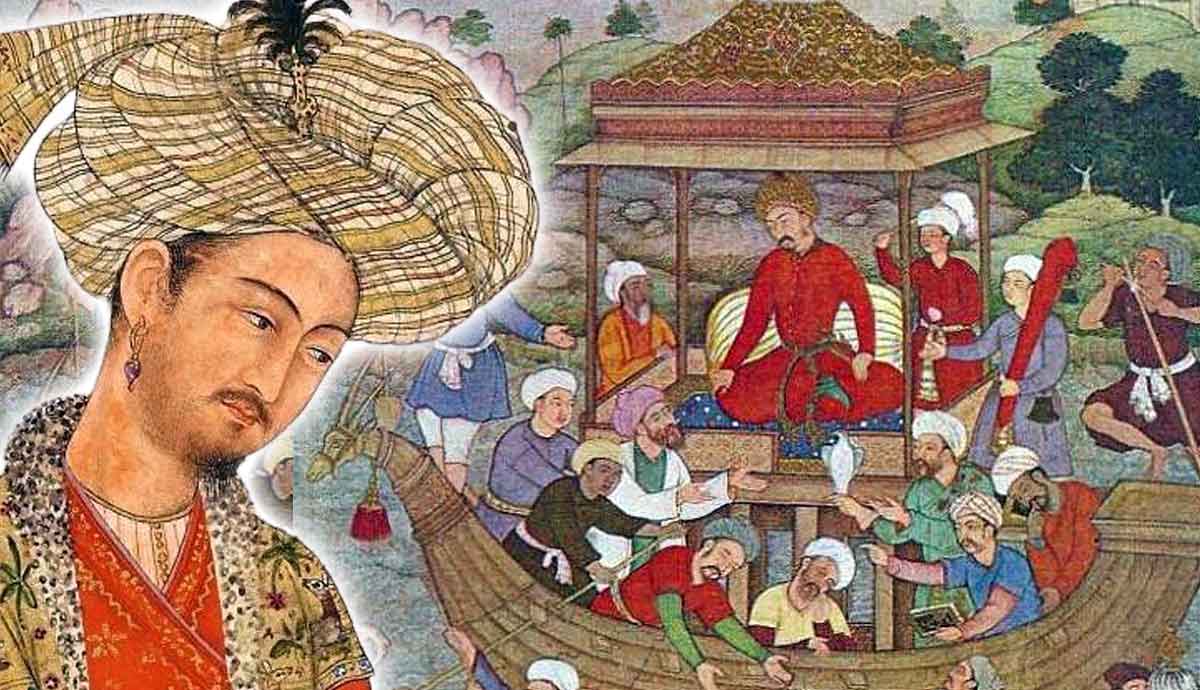

Malik Ambar thus completely stopped Mughal expansion for two decades. The Mughal emperor Jahangir considered Ambar his arch-nemesis. He would repeatedly go off on angry tirades against him. Being completely frustrated by the Abyssinian, he would fantasize about defeating Ambar, as was the case when he commissioned the below painting.

Jahangir, or “world conqueror” ( a name he took for himself), ascended the throne in 1605, after the death of Akbar, the greatest Mughal. Widely regarded as weak and incapable, he has been called the Indian Claudius. Perhaps the only notable thing about his intoxicated and opiated reign, apart from his persecution of various people, is his wife.

After the death of her husband under dubious circumstances, Nur Jahan married Jahangir in 1611. She quickly became the real power behind the throne. She is the only Mughal woman to have coins minted in her name. When the emperor was sick, she held court by herself. When he was ridiculously captured by a lowly general, she rode into battle on an elephant to free him. It was this remarkable woman that Malik Ambar really faced.

Jahangir has the dubious honor of having not one but two of his sons rebelling against him. The first son he would have blinded. The second revolt came in 1622. Nur Jahan was trying to set up her own son-in-law to be declared heir. Prince Khurram, fearful of Nur Jahan’s influence on his weak father, marched against the two. Over the next two years, the rebel prince would fight against his father. Malik Ambar would be a key ally of his. Although Khurram would lose, Jahangir was forced to forgive him. This paved the way for his eventual succession to the Mughal throne as Shah Jahan – the man who built the Taj Mahal.

The Battle of Bhatvadi

Malik Ambar’s final test would come in 1624. The Mughals, perhaps irked by his hand in the princely rebellion, raised a great host. Moreover, the Bijapuri Sultan, previously an ally of Ambar, broke from the Deccani coalition. The Mughals had enticed him with the promise of carving up Ahmednagar, leaving Ambar completely surrounded.

Undeterred, the now 76-year-old general set off on his most brilliant campaign. He raided the territories of his enemies, forcing them to seek battle on his terms. The combined Mughal-Bijapuri army arrived on 10th September to the town of Bhatvadi, where Ambar was waiting. Taking advantage of heavy rain, he destroyed the dam of a nearby lake.

While he held the upper ground, the enemy army camped in the lowlands was rendered completely immobile by the resulting flood. With the Mughal artillery and elephants stuck, Ambar launched daring night raids on the enemy’s camp. The demoralized enemy soldiers began to defect. Finally, Ambar led a great cavalry charge that forced the enemy force to retreat, utterly destroyed. With this great victory, Ambar managed to secure his realm’s independence for years. It would be the crowning achievement of his incredible career. The might of the great Mughal Empire had tried to destroy him for two decades and failed utterly. But Ambar’s time was coming to an end.

Malik Ambar: His Death and Legacy

Malik Ambar died peacefully in 1626, at the ripe old age of 78. His son succeeded him as Prime Minister, but unfortunately, he was no substitute. Shah Jahan, that former ally of Ambar’s, would finally annex Ahmednagar in 1636, ending four decades of resistance.

Malik Ambar’s legacy still lives on to this day. It was under him that the Marathas first emerged as a military and political force. He was a mentor to the Maratha chief Shahaji Bhosale, whose legendary son Shivaji would establish the Maratha Empire. The Marathas would be the ones to defeat the Mughal Empire, in spirit avenging Malik Ambar.

His mark can be found all over Aurangabad, which remains a vibrant and diverse Indian city, home to over a million Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists, Jains, Sikhs, and Christians. But perhaps most importantly, Malik Ambar is a symbol. As the most famous representative of South Asia’s Siddi community (which has many more stories to offer from its rich history, from the impregnable sea kingdom of Janjira to Sidi Badr, the tyrant king of Bengal), he symbolizes the incredible versatility of the human race.

Ambar reminds us that history is not a monolith, not just what we assume of it. He reminds us that our diversity is ancient and worth celebrating, and that incredible stories can be found in our shared past; we need only look.