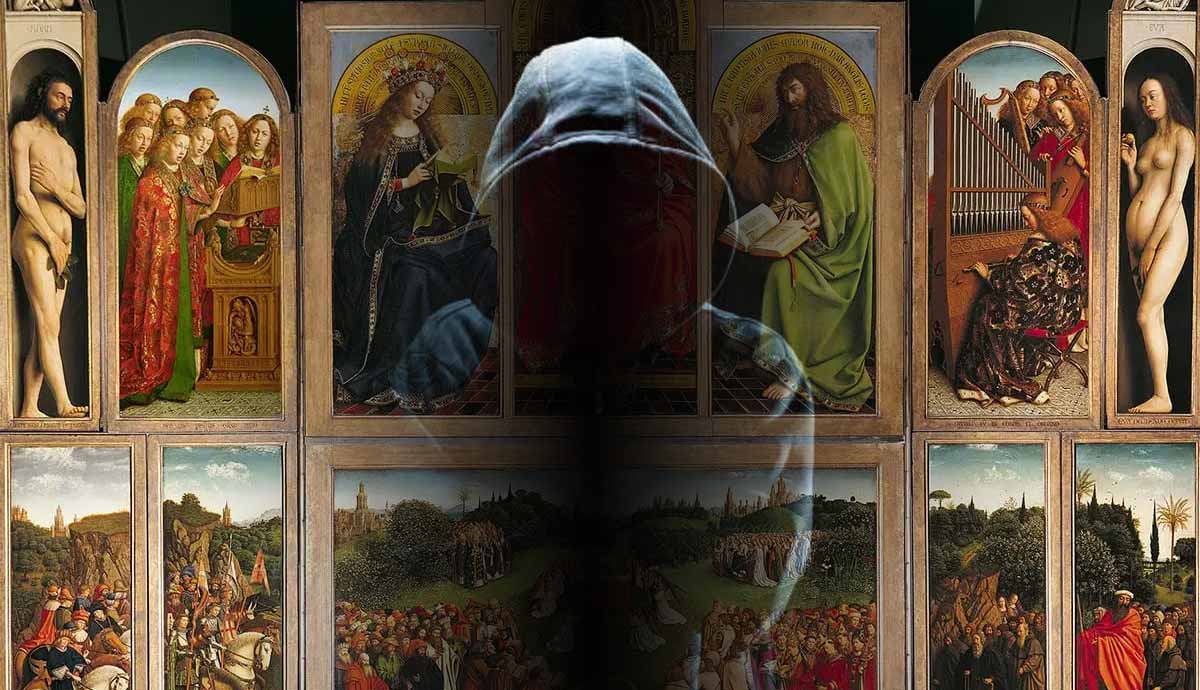

The Ghent Altarpiece, or the Adoration of the Lamb, was completed by Flemish Renaissance brothers Hubert and Jan van Eyck in 1432. A remarkable feat in human achievement, this richly complex, multi-panel altarpiece is recognized as the first major oil painting. Its glistening detail, jewel-like colors, and rich layers of Christian iconography have fascinated audiences for centuries. So much so, the Ghent Altarpiece has fallen victim to around 13 different crimes in its 600-year history. These include several major international thefts, prompting its title as “the most stolen artwork of all time.” We take a brief look through the altarpiece’s most notorious robberies over the centuries.

Napoleon Bonaparte – 1794

Having already escaped destruction during the riotous Calvinistic iconoclasm of the 8th and 9th centuries thanks to high security protection, the Ghent Altarpiece earned quite the reputation as an artwork of great historical significance. One Italian cardinal even called it “The finest painting in Christendom.” This meant by the time of the French Revolution, Napoleon Bonaparte had set his eyes on the prize. In 1794 he sent his troops to steal four of the altarpiece’s panels from its resting place at St Bavo’s Cathedral. After successfully looting four panels from the Ghent Altarpiece, the French proudly put them on display at the recently opened Louvre Museum in the center of Paris. Following Napoleon’s defeat during the Battle of Waterloo, the panels of the Ghent altarpiece returned to their rightful owner, along with many other works of art.

St Bavo’s Cathedral’s Vicar-General – 1815

In 1815, St Bavo Cathedral’s vicar-general pawned and eventually sold six panels from the altarpiece in an attempt to repay his debts. He claimed he sold the panels because they were old and worm eaten, when in reality they were in mint condition. The sold panels passed through several salesmen before making their way into the hands of the king of Prussia. From there they went on display in Berlin for the next 100 years, thus tying them to German history.

German Soldiers in World War I

During World War I, Germans tried to steal the rest of the altarpiece to go with their six panels. But a church custodian intercepted their theft, hiding the panels between the walls and floorboards of the bishop’s residence, before smuggling them to a safe location in the countryside. Following the end of the war, the Treaty of Versailles made the restoration of this masterwork one of its conditions. This meant the six Berlin panels made their way back to their rightful place with the rest of the altarpiece at St Bavo’s in Ghent, thus reuniting the entire artwork for the first time in a century.

Unknown Perpetrators – 1934

The peace didn’t last long. On the 10th of April 1934, a group of unknown criminals broke into St Bavo’s cathedral and stole the lower left joined panels of the altarpiece featuring the Just Judges and St John the Baptist. The criminals left one part of the panel in Ghent train station, and sent a ransom letter for 1 million francs in exchange for the Just Judges panel. Officials refused to pay, and sadly, despite extensive searches, the panel is still missing. However, the highly respected Belgian copyist Jef Van der Veken painted a replica to replace the missing part in 1939.

Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party – 1940

Both Adolf Hitler and Hermann Goering were keen admirers of the Ghent Altarpiece, and believed they had the right to retrieve it as a corrective to the Treaty of Versailles. Belgian officials tried to hide the altarpiece by transporting it to the Vatican in Rome. But the Nazis intercepted them en route, siezing the painting and bundling it off to Pau in South of France. They then carried it to Neuschwanstein Castle in Germany in 1942. From there, Nazis stashed the altarpiece in the huge repository at the Altaussee salt mine in Austria, along with many other stolen works of art and treasures.

In 1945 following the collapse of the German offensive, the Monuments Men and Women of the US army recovered the Ghent Altarpiece along with 400 tons of stolen art. Without their work, many rare and priceless gems in the mine could have been blown apart by the retreating Nazis. Finally, the Ghent Altarpiece returned to St Bavo’s Cathedral in Ghent, Belgium in October 1945, where it remains today.