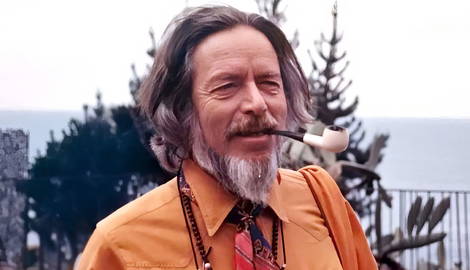

Alan Watts was a British philosopher, author, and speaker famous for bridging Eastern and Western thought. His works were greatly instrumental in popularizing the philosophies of Buddhism, Hinduism, and Taoism in the West. Although Watts came from a Christian background, he found his vocation as a spokesman of the East, channeling its ancient wisdom into a modern and accessible form.

How Did Watts Transition from Dogmatism to Mysticism?

Alan Watts was born in 1915 in a village called Chislehurst in England. Enchanted by the mesmerizing landscape of the countryside, Watts grew appreciative of nature and aesthetics. According to him, his connection to nature sparked his interest in mysticism from a very young age. In his childhood home, there was a place that he called the ‘magic room’, decorated with oriental ornaments and artworks from the Far East that were gifted to his mother. There, his father narrated marvelous tales by Rudyard Kipling that captivated Watts with their exotic and mystical allure, persuading him “to have more sympathy for Buddhism than Christianity”. Aside from the tales, Watts was never a religionist, despite the effort of his parents to make him one.

In his autobiography, In My Own Way, Watts wittily recounted his weekly visits to the Church, concluding that “one of the main reasons for the obsolescence of the Church of England and, for that matter, for the collapse of the British Empire, is that the children could not bring themselves to take it seriously” (Watts, 1972). His parents sent him to several boarding schools, including the King’s School Canterbury, a prestigious religious school, in which he faced rigorous religious indoctrination in what he humorously called ‘muscular Christianity’. As soon as Watts was exposed to this dogmatic training, he lost his love for nature. Undoubtedly, the harsh and maudlin institutionalized religious education left him dispirited.

When Did He Show an Interest in Eastern Religion?

Despite a waning interest in Christianity, Watts maintained an inclination towards the mystical. Since as early as 11 years old, he reported being aware, whenever he competed with his friends in games, “that beyond and beneath the superficial personality of “Alan Watts” there is an eternal and invulnerable center which Hindus would call the atman” (Watts, 1972). At Canterbury, he was introduced to the works of Lafcadio Hearn, and later in vacations in France with Francis Coshaw, he was guided through works on Buddhism. Eventually, Watts joined the London Buddhist Lodge, becoming its secretary at only 16, where he learned various practices under the guidance of Dimitrije Mitrinović, a former student of G. I. Gurdjieff.

When Did Alan Watts Bid a Final Farewell to Christianity?

Watts couldn’t afford to acquire higher education without a scholarship, although he had an opportunity to study at Oxford due to his outstanding academic excellence. As an avid reader, Watts didn’t mind, for according to him “no literate, inquisitive, and imaginative person needs to go to college unless in need of a union card, or degree” for technical purposes (Watts, 1972). Instead, he supported himself through a temporary job at his father’s office and designed his own higher education under the guidance of Nigel Watkins, who became his “bibliographer on Buddhism, comparative religion, and mysticism” (Watts, 1972). Meanwhile, Watts had started writing for the Lodge’s journal and for a magazine called The Eleventh Hour, leading to the publication of his first book at the age of only 21. The Spirit of Zen, published in 1936, marked his debut as an author.

In 1938, Watts moved to the United States and earned a master’s in theology from the Seabury-Western Theological Seminary for his thesis: Behold the Spirit: A Study in the Necessity of Mystical Religion. Watts suffered from the inner conflict between the atmospheres of Buddhism and Christianity, for although he admits that both intellectually reconcile, he couldn’t relate to the ethos that colored his colleagues. Nevertheless, in 1945, Watts started serving as a priest for the next five years. He explained that he “chose priesthood because it was the only formal role of Western society into which, at that time, I could even begin to fit”, despite describing himself as rather a ‘bohemian shaman’ (Watts, 1972).

Watts resigned from the priesthood in 1950 after realizing the great schism between his values and orthodox organized religion. After publishing his book, The Wisdom of Insecurity, he discovered that it’s not just a conflict of beliefs that led to this decision, but a problem with beliefs themselves. Watts didn’t “believe in believing”, deeming beliefs as the “antithesis of faith, as anxiety rather than trust, as holding on rather than letting go” (Watts, 1972).

What Did Allan Watts Say About Letting Go ?

In the 1950s, Watts started teaching at the American Academy of Asian Studies (AAAS) and started a weekly radio show at the KPFA station in Berkley that made him gain tremendous popularity. During these years, he gave many seminars and lectures throughout America where he eloquently adapted and presented the wisdom of the Eastern traditions he studied. In 1957, he published his first best-seller book called The Way of Zen, which was largely instrumental in introducing and popularizing Zen Buddhism in the West, contributing to the ‘counterculture’ literature of the 1960s.

Watts continued to give numerous talks and seminars both throughout the United States and Europe, where he also met prominent psychologist Carl Jung on one of his trips. Although he was a professor at AAAS, a scholar at San Jose State University, and had a fellowship at Harvard University, Watts preferred to describe himself as a ‘philosophical entertainer’ rather than an academic. Like most mystic philosophers, Watts had a great sense of humor.

In the late 1960s, Watts joined a community of bohemian artists and lived on a ferryboat in Sausalito with renowned artist Jean Verda. During this period, he wrote The Book: On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are, which provided an accessible interpretation of Vedanta philosophy. To focus more on his writing, Watts moved to a mountain cabin near Mount Tamalpais where he became a member of the Druid Heights art community and wrote his autobiography and mountain journals, later published as Cloud Hidden, Whereabouts Unknown, among other books.

The last book he wrote, Tao: The Watercourse Way, published posthumously, presented his approach towards death. Watts died in 1973. According to his son, Watts prepared for his own demise 6 months in advance, accepting and aware of his mortality. His wife, Mary Jane Watts, recounted that her late husband had told her that “the secret to life is knowing when to stop”.