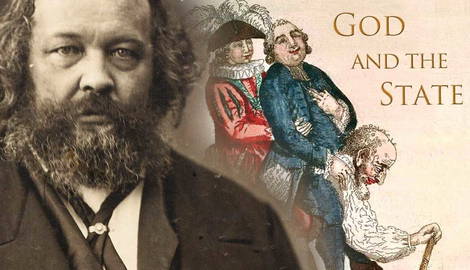

Perhaps most famous for his aphorism, “The passion for destruction is also a creative passion,” Mikhail Bakunin was one of the most important 19th-century anarchists and revolutionaries. Since then, he has fallen into relative obscurity. In this article, we explore Bakunin’s life and works, paying particular attention to his dispute with Marx and his views on authority.

Mikhail Bakunin’s Early Life: Aristocrat, Serviceman, Philosopher

Born Mikhail Aleksandrovich Bakunin on May 30th, 1814, Bakunin was a Russian anarchist, revolutionary, and writer. Like his fellow Russian anarchist Pyotr Kropotkin, Bakunin was the son of a wealthy landowner who spent his formative years in a prestigious military academy training to be an artilleryman (Kinna, 2019, p. 275). In Tsarist Russia, this was not unusual: most revolutionaries were nobles.

Dissatisfied with army life, Bakunin deserted at the age of 21 in order to devote himself to the study of philosophy, particularly the philosophy of Johann Fichte and Fredrich Hegel. His study of Hegel led him to leave Russia in 1840, traveling to Berlin to join the Young Hegelians, a radical group of Hegel students of which Karl Marx had also been a part.

It was in Germany that Bakunin started his revolutionary writing, which would continue over the course of his life. After spending time in Dresden, Switzerland, and Belgium, Bakunin settled in Paris, where he met both Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Karl Marx.

Bakunin the Revolutionary

In contrast to his fellow anarchist Pyotr Kropotkin, Bakunin was more of a revolutionary than an academic (Honderich, 1995, p. 77). Bakunin did not develop a consistent body of theory, preferring the roles of pamphleteer and polemicist, directing his attention to specific issues. His legacy within the anarchist tradition, however, was guaranteed by his exuberant personality, his polemical engagement with his contemporaries, and his ceaseless grass-roots organizing across Europe.

During his time in Paris, Bakunin was embroiled in the Revolution of 1848. Unlike his contemporary Proudhon, however, Bakunin was not put off by the growing violence that characterized anti-authoritarian movements. Instead, he saw violent revolution by the working classes as one of the main ways of creating a more just world. To this end, Bakunin traveled eastwards from Paris, attempting to fan the flames of the 1848 revolution to ensure its spread across Europe. It was these revolutionary activities that led to his capture by the Hamburg empire, and his long imprisonment in Russia.

Released in 1857, Bakunin was exiled to Siberia, where he married Antonia Kwaitkowska, the daughter of a Polish merchant (Kinna, 2019, p. 275). But he would not stay there long. Using commerce as a pretext, Bakunin was given permission to travel south in 1861, where he boarded an American ship bound for Japan. From there, he traveled onward to San Francisco and spent time in Boston and Cambridge, Massachusetts, before eventually sailing to London. After a brief stint in London, Bakunin resumed his itinerant life, spending time in Italy and Geneva, where he developed the anarchist ideas he became famous for and worked to organize a network of secret revolutionary societies.

Bakunin and Marx

During his later life in Geneva, Bakunin joined the First International, an international federation of working men’s groups founded in London in 1864, which aimed to abolish capitalist states in favor of a federation of socialist communities. It was at the meetings in 1868-1872 that Bakunin and Marx clashed (Kinna, 2019, p. 14).

Like Proudhon, Bakunin took issue with Marx’s authoritarianism, his preference for political centralization, and his insistence that revolutionaries must use the power and institutions of the state (e.g., by forming political parties) to achieve socialism. Contra this, Bakunin argued that political power is inherently oppressive, regardless of whether it is held by the bourgeoisie or the proletariat (Honderich, 1995, p. 7). Engaging with lawmaking thus runs the risk of perpetuating the very oppression revolutionaries sought to oppose (Kinna, 2019, p. 15). In order to achieve Bakunin’s vision of socialist anarchism, we ought to overthrow the state without delay. Unless we do so, any revolution is likely to descend into a new form of tyranny which will ultimately have to be overthrown.

Bakunin and Authority

In his essay What is Authority? Michael Bakunin is highly critical of voting and political participation as a way of instigating change, which has since become a core anarchist belief. Even if universal suffrage was achieved, and all adults could vote, this would not end political tyranny. Soon enough, a class of politicians would emerge, in effect creating a political aristocracy or oligarchy. As a consequence, anarchists should

“…reject all legislation, all authority, and every privileged, licensed, official, and legal influence, even that arising from universal suffrage, convinced that it can only ever turn to the advantage of a dominant, exploiting minority and against the interests of the immense, subjugated majority. It is in this sense that we are really anarchists”.

(Bakunin, 1970, p. 35)

Real freedom, Bakunin argued, is incompatible with the state, whether socialist or capitalist. Given how interconnected people’s lives are, however, real freedom for all, is also incompatible with everyone simply doing what they want. Some form of coordination is necessary, but how can we do this without violating people’s freedom and perpetuating tyranny? The answer, Bakunin argues, lies in the creation of a non-governmental system based on voluntary cooperation without private property, with each being rewarded in proportion to their contribution to the furthering of the collective good (Honderich, 1995, p. 77).

Bakunin’s rejection of political authority, he is quick to add, is not a rejection of all forms of authority. He writes:

“When it is a question of boots, I refer the matter to the authority of the cobbler; when it is a question of houses, canals, or railroads, I consult that of the architect or engineer. For each special area of knowledge I speak to the appropriate expert. But I allow neither the cobbler nor the architect nor the scientist to impose upon me.”

(Bakunin, 1970, p. 32)

The key, in Bakunin’s view, is to ensure that those with specific authority in one domain do not acquire authority in all domains. When we do submit to the authority of someone, to maintain our freedom, we must do so because our own faculty of reason tells us to. If our submission is voluntary and based on who is most skilled:

“Each is a directing authority and each is directed in his turn. So there is no fixed and constant authority, but a continual exchange of mutual, temporary, and above all, voluntary authority and subordination”.

(Bakunin, 1970, p. 33)

Mikhail Bakunin’s God and the State (1882)

As Paul Avrich points out in his introduction to God and the State, it is not an easy read. Published posthumously, it is unfinished, repetitive, poorly organized, full of unnecessary digressions (Bakunin, 1970, p. vii), and long footnotes. Notwithstanding, the flashes of brilliance it contains have led to it being the most often read and quoted of Bakunin’s works.

In God and the State, Bakunin argues that, of all of the groups who exploit common people, the chief enslavers of humanity are the church and the state. It is in the very essence of religion, Bakunin argues, to deny the importance of freedom and equality for humanity. If god is the master, we are all slaves. Inverting Voltaire’s famous phrase, “If god doesn’t exist, we would have to create him,” Bakunin concludes that “If god existed, it would be necessary to abolish him.” If we are to be free, we must reject both religious belief and political authority in the real world.

Mikhail Bakunin’s Statism and Anarchy (1873)

Although technically incomplete, Statism and Anarchy forms a more comprehensive whole than many of Bakunin’s other works, which tend to survive in fragments. Statism and Anarchy, the last major work Bakunin completed in his lifetime, reiterates his critiques of Marxism and of the use of the state as a means of ensuring socialism. However, it also contains the most complete outline of Bakunin’s own anarchist views.

Using the famous french revolutionary phrase “Liberté, egalité, fraternité” as his building block, Bakunin argues that true liberty and equality can only be achieved through a renewed focus on brotherhood. Like Kropotkin, Bakunin believed that solidarity was an inherent part of human nature that has been suppressed by social and political conditions. What is needed to let it flourish, is the destruction of the structures that limit it. Bakunin calls for a new society, organized “from below,” made up of small voluntary communities federated together for the achievement of larger purposes as and when these become necessary.

Here, Bakunin implicitly rejects the Marxist view that the urban proletariat should be at the forefront of the revolution, whom he saw as already influenced by bourgeois values, preferring instead to place his faith in the revolutionary potential of those most excluded: the Russian peasantry and the non-urban craftsman.

References

Bakunin, Mikhail. (1970) God and the State. Dover Publications, New York.

Kinna, Ruth. (2019) The Government of No One: The Theory and Practice of Anarchism. Pelican Books, London.

Honderich, Ted. (1995) The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Kinna, Ruth. (2009) Anarchism: A Beginner’s Guide. Oneworld, Oxford.