Elena de Céspedes probably wouldn’t be remembered by history if they hadn’t been charged, tried, and convicted by the Spanish Inquisition in the 16th century. Today, Céspedes would likely be considered intersex, non-binary, or possibly transgender, but such distinctions didn’t exist in Spain more than four centuries ago. Subjected to humiliating medical examinations, Céspedes tried to argue at their Spanish Inquisition trial that they had committed no crimes. Céspedes was also notable for coming from a humble background to eventually qualify as a surgeon.

Elena de Céspedes’ Early Years

Elena de Céspedes was born around 1545 in Alhama de Granada in Andalusia, Spain to Francisca de Medina, an enslaved Black Muslim woman, and Pero Hernández, a free, Christian, Castilian peasant. As an infant, Elena was branded on the cheeks to indicate that they were the mulatto offspring of a slave. Céspedes was freed from slavery as a child and later took the surname of a former owner’s wife.

At fifteen or sixteen years old, Céspedes married a stonemason named Cristóbal Lombardo. Within a few months, Céspedes was pregnant. Lombardo abandoned Céspedes before the baby was born because they “did not get along.” According to testimony later given by Céspedes, they and Lombardo only lived together “as man and wife” for about three months. After the baby boy was born, Céspedes left the baby with friends and began an itinerant life moving from town to town throughout southern and central Spain.

During this time, Elena de Céspedes changed careers several times to include tailor, hosier, weaver, farmhand, shepherd, soldier, and finally, licensed surgeon. After a fight during which a pimp was stabbed (and Elena was jailed for this), Elena changed from female to male dress, had affairs with women, and began to call themself by the masculine form of their name, Eleno. They later explained to the Spanish Inquisition tribunal that the change to men’s clothes was to disguise them from threats made by the pimp and his friends.

After being released from jail, Eleno found work as a farmhand and a shepherd, but an acquaintance denounced them to the corregidor (a local administrative and judicial official). The corregidor arrested Eleno, but Eleno was released on the condition that they began dressing as a female again. Eleno ignored this and was later involved in putting down the Morisco Revolt as a soldier.

Céspedes was literate; after purchasing several books on surgery and medicine, and with the help of a friend who was a Valencian surgeon, Céspedes trained themself to be a surgeon in Madrid. Céspedes never studied medicine at a university but did obtain a medical license for “bleeding and purging” and another one for surgery. Céspedes worked as a surgeon in Valencia and Madrid for nearly a decade.

Céspedes’s Second Marriage to a Woman

In December 1584, Céspedes and a woman named María del Caño, who was the daughter of an artisan, applied for a marriage certificate. Eleno’s lack of facial hair caused the vicar of Madrid, Juan Baptista Neroni, to question if Eleno was a eunuch. In order to get the vicar’s approval, Eleno was examined (only from the front) by four men (including a doctor). The four men declared that Eleno had male genitalia and wasn’t a eunuch. Céspedes and Caño were given a license to marry.

After the banns were announced, two townspeople told the local priest that Céspedes was “male and female” with genitalia of both sexes. The priest refused to officiate the marriage, so Neroni arranged for Eleno to be subjected to a second examination performed by King Felipe II’s doctor and a Madrid doctor. The examination took place on February 17, 1586, and the doctors reported that Céspedes had male genitalia, as well as characteristics that might indicate a vagina. This was enough for the marriage to get the go-ahead, and Céspedes and Caño were married in April 1586.

More than a year later, in June 1587, the couple was arrested on the charge of sodomy. (In this case, sodomy was defined as an “unnatural” sexual act because it was non-procreative and same-sex). The previous December, Céspedes and Caño had moved to the town of Ocaña because there was a vacancy for a surgeon. The chief mayor of Ocaña had made the accusation because he had known Céspedes at the military encampment in Granada during the Morisco Revolt, where some said that Céspedes was a woman while others said they were both male and female.

The couple was imprisoned in the municipal jail. On July 4, 1587, Céspedes was formally accused of sodomy, deceiving Caño and her father, transvestism, and using witchcraft to appear as a man to earlier medical examiners. Eleno argued that the marriage was legitimate because they had a penis at the time of the marriage to Caño.

The Spanish Inquisition Takes Up Cespedes’ Case

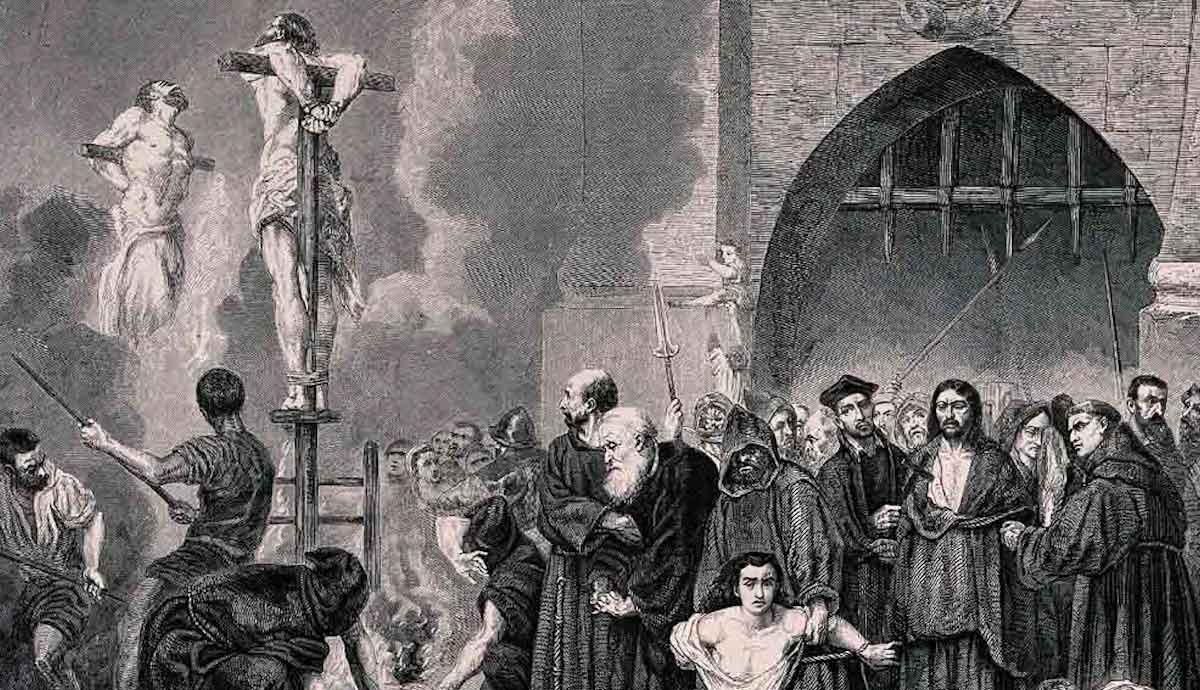

The bailiff asked the vicar general to punish the couple severely, and the penalty for female homosexuality was death. However, the Toledo tribunal of the Spanish Inquisition ordered the secular and episcopal authorities to turn the case over to them because the charge of witchcraft was within the Spanish Inquisition’s jurisdiction. Eleno and María were transferred to an Inquisition jail. The Spanish Inquisition authorities charged Céspedes with sorcery and disrespect for the sacrament of marriage.

The inquisitors focused on Céspedes’s claim to be, in their words, a “hermaphrodite.” Céspedes stated that both their marriage in the 1560s and their marriage in the 1580s were valid because they had been a woman during the first marriage but a man during the second marriage. Céspedes explained how this had happened:

“What happened is that when I gave birth, I did so with such force in my [woman’s] part, that a piece of skin broke out above my urethra and a head emerged about half the size of a thumb, like so, which resembled the swollen head of a male member, which, when I had natural passion and desire, came out, as I said. When I felt desire it got bigger. I gathered the member up and put it back in the place where it had come from so that the skin wouldn’t break.”

Céspedes also told the tribunal that this new organ was initially curved downward by skin, but they were able to use their surgical skills to sever this skin. Céspedes said that from that point on, they were able to use their male organ as men do and even provided names of previous partners who could attest to their sex. Several witnesses, including doctors and female lovers, testified that they had viewed Céspedes as a man.

Céspedes told the tribunal that “…I prepared certain remedies with wine and alcohol, and many other remedies to see if I could close my woman’s part. Even though I couldn’t close it completely, I could squeeze it shut to make it look closed. With all the remedies I prepared, my woman’s part wrinkled up and got so narrow that nothing could be put inside it.”

During the earlier medical examination, Céspedes explained away a “hard wrinkled spot” as “a hemorrhoid I’d gotten, which I cauterized and which had left behind this hard knot.”

Midwives also gave evidence to the tribunal, explaining that they had examined and penetrated what they had interpreted to be Céspedes’s vagina with a candle. The midwives had found Céspedes’s vagina so tight and resistant to penetration that they concluded Céspedes was not only female but also a virgin. Called upon to explain the lack of visible evidence of a penis, Eleno said that it had been injured after a riding injury, and it had been amputated shortly before their imprisonment. King Felipe II’s doctor was ordered to do another examination. This time, the doctor found only female genitalia, but he maintained that he had seen male genitals during his earlier examination.

The inquisitors also argued that Eleno’s wife should have noticed when Céspedes menstruated. Céspedes said they had done, but it had always been an infrequent cycle. Caño told the authorities that when Céspedes had blood on their nightshirt, Céspedes had said that it was bleeding caused by horseback riding.

Cespedes’ Verdict & Sentence

The Toledo medical examiners said that Céspedes was and always had been female, but the tribunal decided not to rule on the “legally messy” charges of sodomy and witchcraft. Instead, Céspedes was convicted of sorcery and disrespect of the sacrament of marriage for failing to document Cristóbal Lombardo’s death before marrying Caño. The tribunal imposed the sentence that male bigamists of that era received: 200 lashes and ten years of confinement. Caño was exonerated of knowingly doing anything wrong and was released.

Céspedes was also subjected to an auto-da-fé, a public ceremony in which sentences of those brought before the Spanish Inquisition were read out, and then the sentences were executed by the secular authorities. Céspedes was paraded around Toledo’s central square in a mitre and robes.

Because of their medical skills, Céspedes was ordered to spend their ten-year sentence looking after the poor in a public hospital while dressed as a woman. Assigned to the Hospital del Rey in Toledo, many people went there just to see Céspedes and to receive treatment from them if necessary. On February 23, 1589, the hospital administrator requested that Céspedes be moved to a more remote facility because their presence was causing an “annoyance and embarrassment.”

Who Was Elena de Céspedes?

Historical and medical studies have since tried to classify Elena de Céspedes as intersex, a hypospadiac male, a lesbian woman, transgender, and non-binary. In Céspedes’s own words, “In reality, I am and was a hermaphrodite. I have and had two natures, one of a man and the other of a woman.”

Céspedes described not only their physiology but was also able to give “behavioral and psychological explanations for his masculinity” that they had lived with for decades. Céspedes also recalled their knowledge of medicine and history, citing Aristotle, Augustine, Cicero, and Pliny to argue that their intersex body was not “unnatural or unprecedented.”

Most of the known information about Elena de Céspedes comes from the Spanish Inquisition trial and the testimony given during it. During the trial, Spanish Inquisition scribes inconsistently used both masculine and feminine pronouns to describe Céspedes. In their own testimony, Céspedes described themself in masculine terms only.