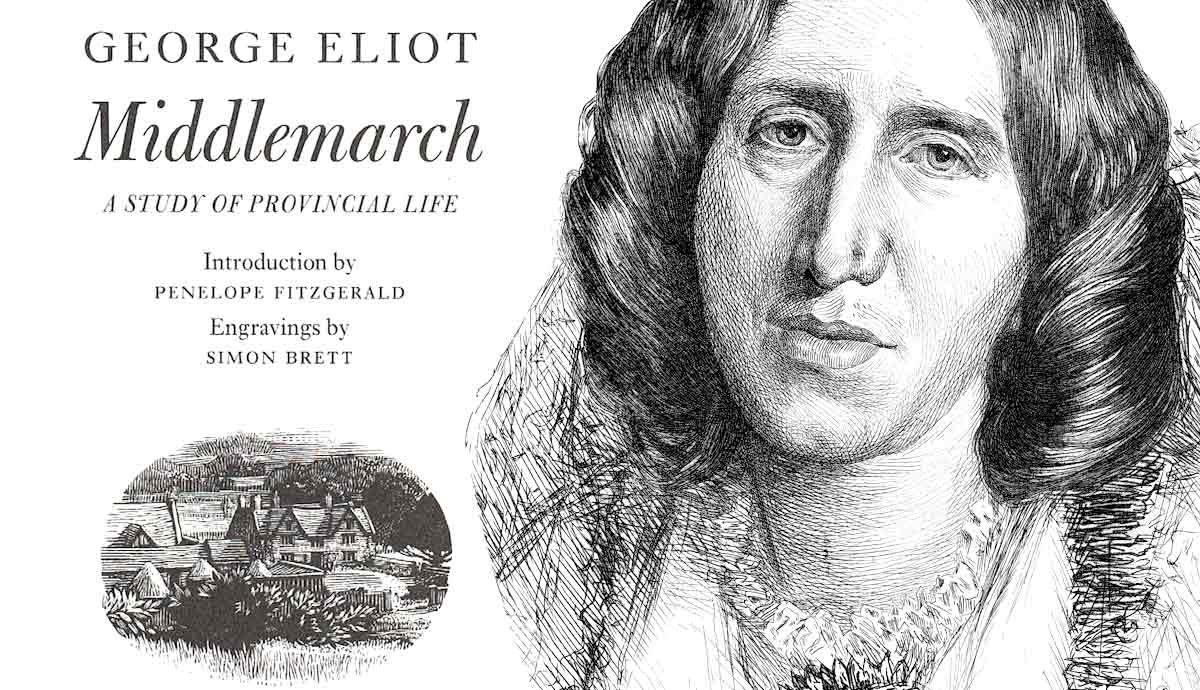

An intellectual polymath and pioneering woman of letters, Mary Ann Evans (also known as George Eliot, the alias under which she published her novels), became a novelist after publishing her essay-cum-manifesto “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists” in the Westminster Review, in which she criticized the triviality of contemporary women’s fiction. Opting instead for the realist mode favored in continental Europe, she went on to write some of the greatest novels of the nineteenth century – and, arguably, of all time. Here, we will take a closer look at her remarkable life and work.

Early Life in the Midlands

Mary Ann Evans was born in Nuneaton, Warwickshire, at South Farm on the Arbury Hall estate (which her father, Robert Evans, managed) on November 22, 1819. From an early age, she demonstrated a keen intelligence and, believing that she was no great beauty and that, therefore, an advantageous marriage would be unlikely, her father allowed her an education otherwise not typically afforded women at the time.

Between the ages of five and sixteen, she boarded at Miss Latham’s school in Attleborough, Mrs. Wallington’s school in Nuneaton, and Miss Franklin’s school in Coventry. After age sixteen, she received little formal education, as her mother, Christiana Evans, passed away, leaving her to fulfill housekeeping duties for her father. Alongside this, however, she was permitted to read from the library of Arbury Hall, which she did voraciously.

Five years after her mother’s death, her brother, Isaac, married. Isaac and his wife moved into the family home, and Evans and her father moved to Coventry. Here, she published work in the Coventry Herald and moved in intellectual circles, through which she was introduced to the likes of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Harriet Martineau, and Herbert Spencer.

Moving in such free-thinking, radical circles also exposed Evans to the theological writings of David Strauss and Ludwig Feuerbach. She went on to publish an English translation of Strauss’s Das Leben Jesu kritisch bearbeitet as The Life of Jesus, Critically Examined (1846) (in which Strauss argued that the miracles of the New Testament should be considered mythical rather than factual). Strauss’ work caused a furor when published in Germany, and Evans’ translation was similarly received.

Mixing such circles led Evans to question her own faith. To appease her father, however, she attended church regularly and continued to keep house for him until his death in 1849.

Moving to London: Becoming George Eliot

Following her father’s death, she moved to London, staying at the home of John Chapman, whose radical press had published her translation of Strauss. Through her connection with Chapman, she became the assistant editor (in truth, the editor in all but name) of his recently purchased left-wing publication, The Westminster Review. She also contributed her own pieces to the journal alongside taking classes in mathematics at the Ladies College in Bedford Square from 1850 to 1851.

In 1851, she also met the philosopher and critic George Henry Lewes. Though Lewes was legally married, he could not obtain a divorce on the grounds of his wife’s infidelity, as theirs had been an open marriage, and he had legally recognized his wife’s children by Thornton Leigh Hunt as his own.

The couple lived together from 1854 when they traveled together to Weimar and Berlin. Though this trip to Germany had been for research purposes, they also considered it a honeymoon of sorts and, in turn, considered themselves married to each other. Evans’ novel, The Mill on the Floss, for example, was dedicated “[t]o my beloved husband, George Henry Lewes, [to whom] I give this MS. of my third book, written in the sixth year of our life together, at Holly Lodge, South Field, Wandsworth, and finished 21 March 1860.”

They made no attempt to conceal their relationship, though this attracted disapproval from Evans’ own family and wider society. Evans, however, did not regret her decision and defiantly declared, “I wish it to be understood that I should never invite any one to come and see me who did not ask for the invitation.”

While working for The Westminster Review, Evans published an essay-cum-manifesto titled “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists,” in which she deplored the triviality of contemporary women’s fiction. When she turned her own talents to writing novels, she therefore resolved to do so in the realist tradition, eschewing the light-hearted, romantic subject matter usually adopted by female writers at the time.

In an attempt to further distance herself from these “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists,” she adopted the pseudonym George Eliot. While adopting her lover’s first name, her pseudonym also granted her a certain level of anonymity, which, in turn, shielded her from some of the scrutiny of those who considered her relationship with Lewes to be scandalous.

Under this nom de plume, in 1857, she published “The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton” (the first of the three stories that constitute Scenes of Clerical Life) in Blackwood’s Magazine. Far from readers suspecting George Eliot to be a woman, Scenes of Clerical Life led many to believe that it was the work of a country parson.

In 1859, she published her first novel, Adam Bede. This was an instant success, being described in a review in The Athenaeum as “a novel of the highest class.” Charles Dickens was an early admirer, and (writing anonymously) Anne Mozley speculated as to whether the author might, in fact, be a woman. In the end, Evans was forced to waive her anonymity when one Joseph Liggins falsely claimed to be the author.

Shortly after the success of Adam Bede, The Mill on the Floss was published in 1860. Fictionalizing some of her own early experiences as a fiercely intelligent girl in a patriarchal society as well as her social disgrace following an extramarital relationship, The Mill on the Floss is among Eliot’s most beloved novels.

A year after The Mill on the Floss was published, Silas Marner – the story of a wrongly accused man who turns away from society, becoming solitary and miserly, before being redeemed through adoptive fatherhood – was released. This was followed by the publication of Romola in Cornhill Magazine in 1862-63. Set in Renaissance Florence in the aftermath of the expulsion of the powerful Medici family, the novel tells the story of Romola, a woman of intelligence and integrity who must break away from her duplicitous husband and forge her own path. Romola is considered one of her most accomplished novels, and the author herself claimed to have written it with her “best blood.”

After Romola came Felix Holt, the Radical in 1866, followed by her most acclaimed novel, Middlemarch, in 1871-72. Widely heralded as the supreme nineteenth-century novel, in focusing on the intersecting lives of the inhabitants of Middlemarch (a fictional Midlands town) on the human level while also paying attention to broader historical events and forces, Middlemarch in many ways is the supreme demonstration of all that the novel can do better than any other form.

In 1876, Eliot’s last novel, Daniel Deronda, was published. The novel charts the wildly differing fortunes of Gwendolen Harleth (the beautiful, spoiled, unhappy wife of Henleigh Mallinger Grandcourt, an emotionally abusive aristocrat whom she has married solely for his wealth) and the idealistic Daniel Deronda, who discovers his vocation after saving a Jewish woman named Mirah Lapidoth from drowning herself in the River Thames. Deronda agrees to help her find her lost family – though he also ends up discovering his own identity in the process. Among other things, the novel is an exploration of guilt and sexuality and has been interpreted as proto-Zionist.

Losing Lewes: The Later Years

By the time Daniel Deronda was published, Evans and Lewes had moved to Witley, Surrey. Lewes’ health was in decline, and he died in 1878. Devastated, Evans dedicated the next two years of her life to editing Lewes’ final work, the latter series of his multi-volume The Problems of Life and Mind.

In 1880, Evans married John Walter Cross, who had been her financial advisor and a friend of hers and Lewes’. While some of her friends were doubtful as to the wisdom of her union with Cross, who was 20 years her junior, her friend, Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon, wrote to reassure her that Lewes would “be glad, as I am, that you have a friend” in Cross.

However, on their honeymoon in Venice, Cross reportedly attempted to commit suicide by jumping from the balcony of their hotel into the Grand Canal. Having survived the attempt, they returned to England and moved into a new home in Chelsea. Evans, however, developed a throat infection, which, combined with a pre-existing kidney disease, proved fatal. She passed away on December 22, 1880, by which time she and Cross had been married for approximately seven months.

Her lost faith and her previous relationship with Lewes meant that Evans was not buried in Westminster Abbey (as one might have expected for a writer of her status) but in London’s Highgate Cemetery, beside Lewes in the section of the cemetery reserved for religious and political dissenters.

However, in 1980, to mark the centenary of her death and in honor of her legacy as a writer, a memorial stone was placed in Poets’ Corner. On the stone is a quotation from Scenes of Clerical Life: “The first condition of human goodness is something to love; the second something to reverence.”