When we envision a progressive person who is ahead of their time, a medieval nun almost certainly doesn’t come to mind. Yet, in the troubled twelfth century, the world was graced by an incredible creative force in the body of a single woman. Hildegard of Bingen was a scholar, an artist, a prolific writer, a healer, and a composer. She also became famous for her God-sent visions which she documented in illuminated manuscripts.

The Turbulent World of Hildegard of Bingen

Hildegard of Bingen, also known as Saint Hildegard or the Sybyl of the Rhyne, was born in the Holy Roman Empire, on the present-day territory of Germany, in 1098. This period, known among historians as the High Middle Ages was dynamic and full of change, ultimately leading to the switch from a relatively liberal Early Middle Ages and a significantly more restrictive and conservative Late Middle Ages period.

The minds of Hildegard’s contemporaries were not at ease. After the end of the first millennium, most scholars and clerics anticipated the second coming of Jesus Christ and Judgment Day. At the same time, the Church was losing its grasp on its followers and various denominations, with the Great Schism of 1054 separating Catholic and Orthodox faiths for good.

While the Pope and his officials demanded more power, secular authorities were reluctant to share. To establish its power further, the Church had to come up with a new common enemy. The Islamic world became the new nemesis, and soon the First Crusade was initiated with the goal to free the holy city of Jerusalem from Muslim influence.

As wars raged in the Levant, Europe enjoyed a boom of intellectual activity which mostly relied on monasteries and convents. A medieval monastery provided its inhabitants with the best possible education and was a central element in the creation and dissemination of the written word, art production, and civil records.

Hildegard was born into a family of minor nobility and was the youngest of ten children. From her early days, her family knew she was going to become a nun, not because she showed a particular inclination to it, but because it had a practical purpose. In relatively wealthy medieval families with several children, the older ones were usually expected to continue their parents’ agenda, while the youngest ones were often sent to convents before their teens. The reason for that was not an unwillingness to provide for yet another child, but a concern for the spiritual well-being of the family. While the oldest kids took care of earthly matters, the youngest ones were supposed to pray for the whole family to ensure their salvation.

However, young Hildegard of Bingen had already shown signs of being an unusual child, capable of seeing and knowing more than others. At the age of four, she told her mother about the spots on the back of a calf that was still in the cow’s womb. After its birth, the family saw that the calf had those exact spots in the exact places Hildegard.

When she was eight, Hildegard moved to a Benedictine convent adjacent to a male monastery. During the following decades, she would read and write, study music and theology, pray, and be subject to a strict day-to-day routine. Her life would change in her early forties after she became the leader of her convent. The previous head of the convent practiced fasting and self-harm to purify her soul through suffering. Hildegard of Bingen advocated against such practices, believing that reasonable comfort of the body was necessary for the comfort of the mind.

The Visions of Hildegard of Bingen

It was only after she established herself as an authority figure that Hildegard started to talk about her visions. Apparently, she had them since her early childhood, but did not trust them and preferred not to share them with anyone. According to Hildegard, all epiphanies started with an intense burst of pain followed by visions of white balls of light. She not only saw her visions but heard, tasted, and smelled them too. She saw stars falling into the ocean and turning black, angels falling, and the world ending. Hildegard of Bingen was sure that it was God talking to her, guiding her way. Centuries later, neurobiologists would state that Hildegard suffered from intense migraines, with her descriptions of balls of light strikingly similar to regular symptoms.

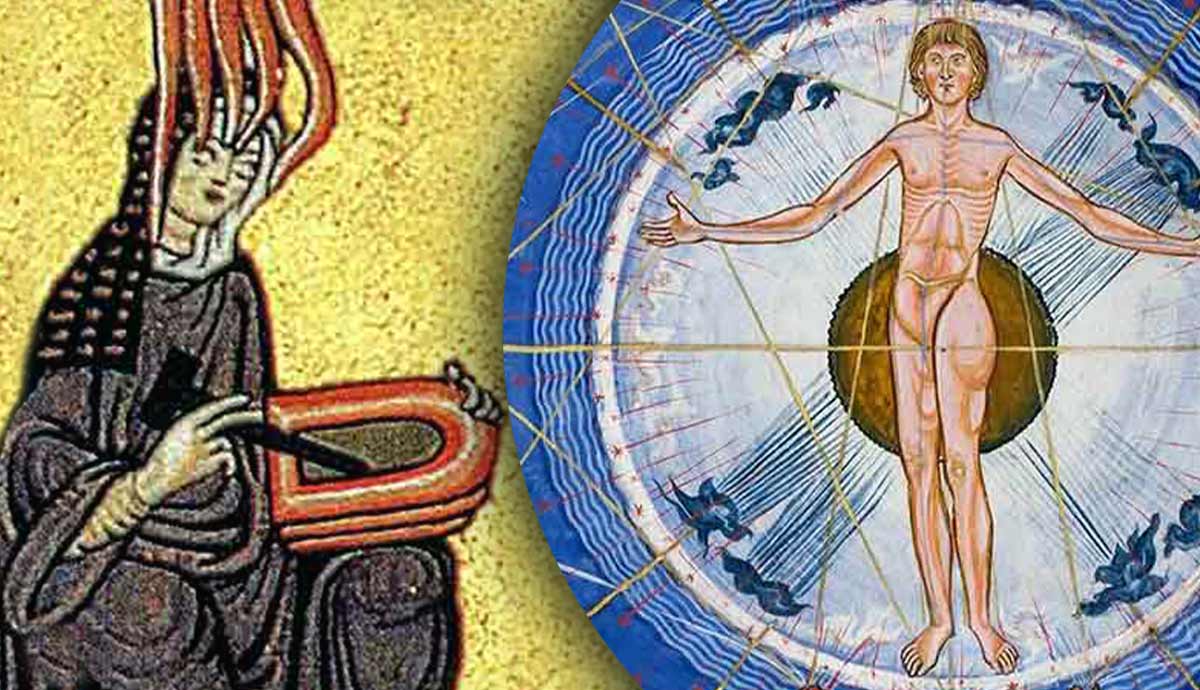

After her initial confession, the church officials became suspicious of Hildegard’s visions, afraid they could be fraudulent, or worse, come from demonic forces. Hildegard’s testimony convinced Pope Eugene III of the authenticity and holiness of her visions, so she was granted official permission to record her visions on paper. In the following decade of her life, she would transcribe and illustrate 26 of her visions which represented the events from the creation of the world to its end. The illustrations of her visions rely on traditional Christian iconography of the time, but they also show unexpected forms, shapes, and narratives.

Music and Healing

Apart from her visions, Hildegard of Bingen was a prolific composer and healer. She believed in a holistic approach to healing, treating not only the wounded part but the entire body and soul. She wrote two books and her medicinal practice, where she drew parallels between the human body and nature, comparing blood vessels to rivers, flesh to earth, and hair to trees and plants. Hildegard also practiced healing with minerals, like applying sapphires to one’s eyes to cure inflammation.

Where medicine tended to the body, music tended to the soul. So, Hildegard of Bingen wrote more than seventy musical pieces with poetry that she performed together with her convent. Her love for music was so immense and well-known that taking it from her would be the greatest punishment of all.

The higher-ranking officials knew it and were not afraid to use it against her at least once. In the late years of Hildegard, she became the center of a great church scandal for allowing an excommunicated young man to be buried in her abbey’s cemetery. Hildegard believed that the man reconciled with his Church before his death and insisted that she received God’s permission for the burial through her visions. The local bishop was furious and ordered an exhumation, but Hildegard and her nuns refused it and hid the man’s grave. Their punishment was swift but had nothing to do with earthly matters such as finances or clerical positions. The bishop intended to inflict a real inconvenience on them, so he prohibited Hildegard’s abbey to play music and sing. The ban lasted for eight months and ended only when Hildegard threatened the bishop with the higher power. In a letter, she wrote about God telling her how those who obstruct playing holy music, would not hear the angels sing in the afterlife.

Hildegard of Bingen and Agency

Apart from her artistic and visionary talents, Hildegard of Bingen was a skilled and professional manager with a good grasp of the way the system worked. After being appointed the head of her convent, she single-handedly decided to move her nuns to a separate monastery, establishing her own abbey. She had political influence as well, corresponding regularly with figures like the German emperor Frederick I Barbarossa, to whom she fearlessly threatened with God’s wrath at least once.

Despite the relative liberality of the High Middle Ages, Europe at the time was not exactly a friendly place for women in power. So how did Hildegard of Bingen manage to climb so high on the clerical ladder and remain an important part of history for centuries?

One of the main reasons for Hildegard of Bingen’s success could be seen in her deliberate shifting of agency and appeal to the higher power. Instead of stating that she herself was the one who made decisions and expressed opinions, she repeatedly insisted on being God’s messenger. Despite her enormous creative output and many accomplishments, Hildegard knew the rules of the society she was born into, and operated within its limits, hardly ever crossing the line. She was not a feminist icon either: in her correspondence, she complained about the weakness of the female sex and the (rather questionable) fact that women were allowed to do too much in her days. In a way she dissociated from her gender, comparing herself not to a bride of Christ but to male figures like Saint John the Apostle.

Nonetheless, as the head of her convent and abbey, she was a liberal and kind leader, allowing her nuns to dress up for holidays and celebrate. Despite her position as a woman leader in a male-dominated world, she remained empathetic and was deeply loved by her nuns. Unlike many other church fathers, Hildegard of Bingen’s faith was not about excessive limitations and fear of punishment, but about the celebration of life and God’s creativity through art.