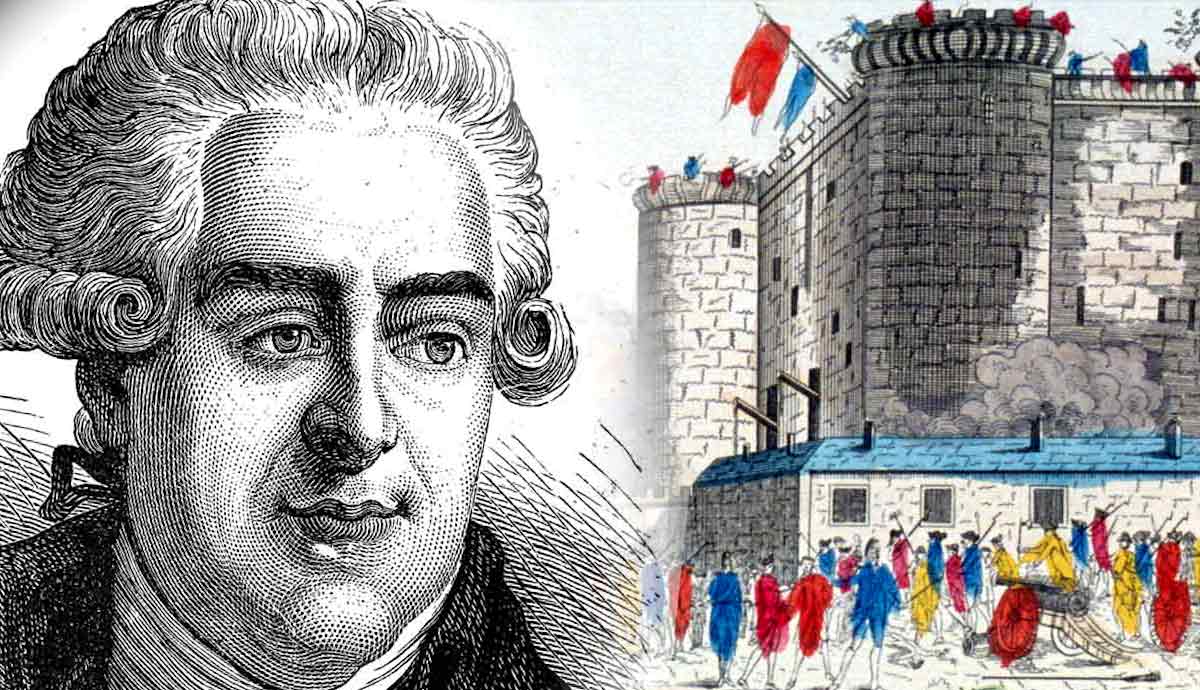

Rebel. Celebrity. Hero. Traitor. Corsican revolutionary leader Pasquale Paoli was one of Europe’s most famous and divisive personalities of the late eighteenth century. His admirers included the likes of Enlightenment philosophers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau and a young fellow Corsican named Napoleon Bonaparte.

But undoubtedly, Paoli’s fame was eclipsed by Napoleon’s. Nevertheless, Paoli’s story is fascinating. However, before we get into the details of Paoli’s life, it is important to learn about the Mediterranean island that both Paoli and Napoleon called home: Corsica.

Corsica

Today, the Mediterranean island of Corsica is a Department of France. However, historically, culturally, and linguistically, the island has long been connected to Italy. Indeed, as Patrice Gueniffey explains, Pasquale Paoli and Napoleon Bonaparte came from Corsican and Italian origins.

At the time of Pasquale Paoli’s birth in April 1725, Corsica belonged to the Republic of Genoa. In earlier times, Genoa was second only to its rival, the Republic of Venice, in terms of Italian commercial and maritime supremacy.

But by the eighteenth century, Genoa had fallen into decline. Genoese rule in Corsica could not extend beyond the island’s coastal towns.

Thus, the island’s forbidding mountainous interior became a bastion of resistance to Genoese and later French rule. Pasquale’s father, Giacinto Paoli, led the Corsicans in revolt against the Genoese in 1735. However, the rebellion was suppressed by 1739.

Paoli the Rebel

Given his father’s background, one could say becoming a rebel meant joining the family business for young Pasquale. Indeed, Pasquale got his first taste of exile by joining his father in Naples in 1739. Patrice Gueniffey says that the period of Neapolitan exile first exposed Paoli to Enlightenment ideas.

While in Naples, Paoli attended the military academy and plotted his return to fulfill his father’s goal of Corsican independence from Genoa. His military career began under his father’s command in 1741 in the Royal Neapolitan Army’s Corsican regiment.

In 1755, Paoli returned to Corsica and led a rebellion against the Genoese. By that summer, he had driven the Genoese out of the island except for a few fortified garrisons in coastal towns. The stage was set for Paoli to declare Corsica an independent republic.

An International Celebrity

Paoli’s rebellion and victory over the Genoese became an international sensation. Indeed, by this time, Paoli was considered a hero of the Enlightenment. As Cedric Oliva notes, Paoli’s introduction of a Corsican Constitution in 1755 had made him the darling of Enlightenment intellectuals. Oliva points out that this was one of the world’s first written constitutions to grant substantial rights to its citizens.

However, as Patrice Gueniffey pointed out, these constitutional rights mainly existed on paper. Instead, actual power was increasingly concentrated in Paoli’s hands. And this is precisely what many Corsicans desired. For instance, a young Napoleon Bonaparte numbered among Paoli’s many admirers. Indeed, for many Corsicans, Paoli was more than a celebrity. He was U Babbu di a Patria (the Father of the Country).

Paoli’s fame spread far beyond Corsica’s shores. He was even honored as far away as British North America with the founding of Paoli, Pennsylvania. Indeed, Paoli later became a source of inspiration for American patriots during the American Revolution.

Paoli largely had Scottish writer and grand tourist James Boswell to thank for his celebrity status. Gueniffey says that Boswell had been persuaded to visit Corsica and meet Paoli by none other than Enlightenment philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

Boswell’s trip to Corsica in 1765 resulted in a close friendship with Paoli and a popular book about the island and its revolutionary hero. Indeed, Boswell became such a proponent of Corsican independence that he became known as “Corsica Boswell.”

But Corsica’s days under Paoli’s control were numbered. By 1764, Genoa had an ally in its war to retake Corsica: the French. In 1768, cash-strapped Genoa sold Corsica to Continental Europe’s great military power, the Kingdom of France.

Defeat, Exile, and Revolution

France’s purchase of Corsica from the Republic of Genoa in 1768 dramatically changed the situation for Paoli and his supporters. While Paoli’s Corsican rebels could hold off Genoese attacks, the Genoese were not the French in terms of military capability.

At first, Paoli’s Corsican rebels appeared capable of resisting the French. For example, in 1768, the Corsicans won an unexpected victory over French troops at the Battle of Borgo.

However, by early 1769, the French were in a position to overwhelm Paoli and his rebels. In early May 1769, French forces under the Comte de Vaux defeated Corsican rebels at the Battle of Ponte Novu. At this point, Paoli and many of his closest supporters chose exile rather than submit to French rule. Paoli went to London and received a pension from King George III.

Perhaps Paoli’s most famous supporters who did not follow him into exile were Napoleon’s parents, Carlo and Letizia. When faced with the decision to remain loyal to Paoli or swear allegiance to France, Carlo placed his faith in France’s King Louis XVI. As David Bell points out, Letizia formed close ties with Corsica’s French governor, the Comte de Marbeuf, which also improved the family’s position.

The Bonaparte family’s fateful decision to swear loyalty to France helped pave the way for Napoleon’s French education and future rise to power, thanks to the French Revolution.

However, just as the French Revolution created opportunities for Napoleon, it also changed Paoli’s fortunes.

A French Hero?

Paoli’s relationship with the French revolutionaries got off to a rocky start. For example, Napoleon’s benefactor and fellow Corsican, Antoine-Christophe Saliceti, got the French National Assembly to recognize Corsica as a French department in January 1790.

Paoli condemned this decision while still in exile as a sign of Paris attempting to centralize its power and influence on the island. On the other hand, Napoleon backed Saliceti’s proposal and approved the National Assembly’s decision.

Nevertheless, the sixty-five-year-old Paoli returned triumphantly to Corsica in July 1790. Napoleon and his older brother Joseph were on Ajaccio’s reception committee. After more than two decades in exile, Paoli returned with great fanfare and new titles.

For example, Paoli became a Lieutenant of Corsica and was elected to the presidencies of the island’s assembly and National Guard.

According to Andrew Roberts, Paoli saw the Bonaparte brothers as children of the collaborators who had turned on him and supported France in the 1760s. He also never fully trusted Napoleon because of his French officer’s commission.

These factors, coupled with the fact that Paoli worked closely with other leading families from the island, meant that Napoleon and his family would be frozen out of Corsica’s social and political leadership.

Enter the British

By early 1793, Paoli and his supporters (Paolists) had turned on the French Revolutionary cause. For his part, Paoli detested the more radical elements of the French Revolution, including King Louis XVI’s execution and the power of the Jacobin faction, to which Napoleon was now an enthusiastic supporter.

A botched campaign against France’s enemies in Sardinia in February 1793 marked the turning point in Paoli’s relationship with France. This campaign is also significant as it marks Napoleon’s first taste of battle. Andrew Roberts says that Paoli had promised to raise 10,000 troops for the campaign that his nephew commanded. However, less than 2,000 took part in the disastrous campaign.

Indeed, by this point, Paoli had opened negotiations with the British. He commanded fortified positions across Corsica and refused to let French forces gain access. In May 1793, Napoleon and Saliceti took part in a failed attack on Ajaccio’s citadel, which remained under Paolist control.

That same month, a frustrated Napoleon wrote a paper condemning Paoli. In early June 1793, the Bonaparte family fled Corsica for France. Paolist mobs ransacked Bonaparte family property. Although he had been critical in 1793, Andrew Roberts notes that in later life, Napoleon spoke “with the greatest respect for Paoli.”

But that time would be much later. At that moment, Paoli invited the British to seize Corsica. By the end of June 1793, Paoli proclaimed King George III of Britain as Corsica’s monarch. In July 1793, British forces arrived to take control of Corsica.

Final Exile

French forces seized Corsica from the British in 1796. Paoli fled Corsica for exile once again in Britain for what would be the last time. He died in London in February 1807.

Napoleon returned to Corsica for just one brief visit on his return from the Egyptian campaign in 1799.

The French honored Paoli, though, in the late nineteenth century. For example, during the centennial celebrations of the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1889, Paoli’s remains were repatriated to his birthplace of Morosaglia in Corsica.