Most of the surviving information we have about Norse mythology and legendary Viking history was written by Snorri Sturluson, a Christian historian and politician living in Iceland in the 13th century. Consequently, much of what we know about Norse mythology and Viking religion is filtered through his perceptions and worldview. So, what exactly do we know about Snorri Sturluson and why did he choose to write about Norse culture?

Icelandic Gentry

Norwegian Vikings started to settle in Iceland from the end of the 9th century, both in search of new lands and to evade new taxes imposed by King Harald Fairhair back in Norway. Iceland converted to Christianity around the year 1000, largely through the influence of the Norwegian King Olaf Tryggvason. At this time, Iceland was an independent commonwealth ruled by local chiefs via the Althing, an early form of parliament. But the Icelanders remained closely connected to their Norwegian cousins.

Snorri Sturluson was born in Iceland in 1179 to Sturla Thordason the Elder, who was from a wealthy family that settled in the west of Iceland in a region called Hvammur i Dolun. He had at least four siblings and nine half-siblings.

According to the Landnamabok, a manuscript that explains how Iceland was settled and records the histories and genealogies of Iceland’s important families, Snorri Sturluson’s family had both Christian and pagan roots. On his father’s side, he could trace his ancestry back to Helgi the Lean, who was an early arrival to Iceland in around 890. He was distinguished from his neighbors by the fact that he was already a Christian at this time. On his mother’s side, Sturluson could trace his ancestry to the pagan settlers Kveld-Ulf and Skalla-Grim, the father of the Icelandic skaldic poet Egil Skallagrimsson. So, Snorri Sturluson had both Norse paganism and Skaldic poetry “in his blood.” But by the end of the 12th century, his family were already Christians.

Fostered to Jon Loftsson

At some point in Snorri Sturluson’s youth, his father Sturla found himself in a legal dispute with a local chief called Pall Solvason. While the proceedings were being heard in front of the Althing, Pall’s wife attacked Sturla with a knife, claiming that she wanted to leave Sturla with just one eye, like his hero, the pagan god Odin. She missed and only slashed his cheek, but this still gave Sturla the right to claim compensation.

Instead of taking Pall’s property and leaving the man bankrupt, another Icelandic chief named Jon Loftsson stepped in as a mediator to broker a deal. As part of the deal, Loftsson agreed to foster and educate Sturla’s son Snorri. Loftsson seems to have had connections to the Norwegian royal family, so this was probably considered an excellent opportunity for the family. When the deal was done, Snorri Sturluson traveled to Oddi in the south of Iceland with Jon Loftsson, and he would never return home.

Living in Oddi, Sturluson studied with Loftsson’s grandfather, a well-known scholar and priest called Saemundr Frodi. He had traveled beyond Vikings lands to France and Germany to study and then set up a school in Oddi. He wrote a history of the Norwegian kings in Latin, which doesn’t survive, and he may also have composed poetry in Old Norse. According to some tales from Icelandic folklore, Saemundr made a pact with the devil to acquire his vast knowledge.

Entering Political Life

Following his studies, Sturluson had political ambitions. While in his 20s, he married a woman called Herdis, which enabled him to inherit her father’s large estate in Borg, not far from Oddi. This made him a local chieftain, giving him political responsibilities. He had at least four children with his wife, but they separated before long because Sturluson was chronically unfaithful.

In 1209, at the age of 30, he moved away from his family and became an estate manager in Reykholt, back in the west country. There he fathered another five children with three different mothers. This obviously did nothing to tarnish his reputation, as in 1215 he was elected lawspeaker.

The position of lawspeaker was extremely important in Iceland. He was president of the Althing, and he was required to recite the established laws and advise the gathered chiefs on how the law should be applied in different situations. While it was technically an advisory role without authority, it came with a lot of influence. Holding the office suggests that Snorri Sturluson had significant political ambitions.

Relationship With Norway

Snorri Sturluson left the role of lawspeaker in 1218 because he was invited to Norway by the royal family, probably because of his connection to Jon Loftsson. While in Norway, he built a relationship with the then-teenage Norwegian King Hakon Hakonarson and his regent Jarl Skuli. He seems to have acted as a court poet, writing verses praising the deeds of the pair and receiving gifts in return.

When Sturluson returned to Iceland in 1220, he had probably been given the mission of helping incorporate Iceland into the Norwegian Empire, something the royal family had wanted for years. So, when he became lawspeaker again in 1222, Snorri Sturluson used his influence to advocate for joining Norway.

Sturluson held the position of lawspeaker for the next ten years and became one of the most popular politicians in Iceland.

He also tried to expand his power and influence by replicating the good fortune of his first marriage. First, he set his sights on a woman called Solveig, who was the granddaughter of his foster father. But his proposal was passed over in favor of a marriage alliance with his political adversary and nephew Sturla Sighvatsson. Sturlasson was left to marry another granddaughter of Loftsson, Hallveig Ormsdottir, in 1224.

While Sturluson advocated for joining Norway, his nephew supported independence, and the two came into conflict. Armed disputes broke out between their respective followers on several occasions. This seems to have been largely driven by Sturluson, who seemed to believe that “saga-worthy” behavior would allow him to unite the people behind him and hand the country to the Norwegian king.

Eventually, the civil unrest in Iceland got so bad that King Hakon invited the Icelandic chiefs to Norway where he could mediate their disputes. Snorri Sturluson advocated for the offer, but his opponents suspected that it was a trap and refused.

Downfall and Death

The ongoing conflict did not go in Sturluson’s favor. Several of his allies were captured by his enemies, and Sturluson himself deserted some of his allies when they questioned his leadership and decisions.

In 1237, Sturluson was forced to return to Norway to seek the protection of his patron. But there, he found himself in the middle of a dispute between King Hakon and his now ex-regent Jarl Skuli, who would try to seize power for himself. Sturluson seems to have allied himself with Skuli in return for the title Jarl, while also trying to maintain the favor of the king.

In 1238, when many of his enemies, including his nephew, had been killed in local conflicts, Sturluson seems to have considered it safer in Iceland than in the middle of Norway’s power dispute. He requested permission to return home. Hakon denied the request, believing that he could no longer trust the Icelander, while Skuli granted it. Sturluson took his opportunity to return in 1239.

Not long after his return to Iceland, Jarl Skuli launched his revolt, which failed. He was killed by Hakon. Sturluson resumed his position as a chief in Iceland and continued to encourage joining with Norway as he tried to wrestle power from the chiefs that had risen in his absence, principally Gissur Thorvaldsson and Kolbein the Young.

Nevertheless, Hakon could no longer trust Sturluson, and he sent agents to Gissur telling him to kill or capture him. While Sturluson received word of the plot against him in a letter in cipher runes, he was unable to understand the cipher and was left unprepared. Gissur with a team of 70 men raided his house in Reykholt in a surprise attack and killed Snorri Sturluson in 1241.

But Snorri Sturluson was still popular, and this caused an outcry in both Iceland and Norway. Consequently, it would take Hakon another 20 years to convince the Icelanders to swear fealty to him. This would happen in 1262, just one year before Hakon died.

Literary Works

Amid all this political intrigue, Snorri Sturluson managed to write two very important works, his Prose Edda and Heimskringla. Both were written in old Icelandic and in a Latin script adapted for that purpose. This reflects the process of conversion and integration into “Christendom” that was underway.

Prose Edda

The Prose Edda is the fullest and most detailed surviving record of Norse mythology. Why did the Christian Sturluson choose to dedicate himself to this subject matter? It was written as a guide to Norse poetry, which relies heavily on “kennings.” These are figurative metaphors used in place of proper nouns. In Old Norse poetry, these are almost always drawn from Norse mythology, so a good understanding of Norse myth was required to understand Old Norse poems and to compose poems in the same genre. Snorri Sturluson put together a guide for poets.

The Prose Edda can be broken down into four sections. The prologue provides a euhemerized account of the identity of the Norse gods, linking them with historical people to make sense of the mythology within Christian ideology.

The next section, the Gylfaginning, retells stories from Norse mythology with a focus on the creation of the world and its destruction at Ragnarok. The next section, the Skaldskaparmal, shares more Norse myths and includes a list of kennings previously used in poetry. The final section, the Hattatal, discusses the composition of traditional Skaldic poetry.

Modern scholars believe that Sturluson drew on existing written manuscripts and oral traditions to compose his mythology, but also suggest that where information was lacking, he invented things to tie everything neatly together. When he did this, he was surely influenced by the new beliefs establishing themselves in Christian Iceland. This is very important because he is the only source for several myths including the creation myth and the story of the death of Balder.

While all his stories are probably based on genuine myths, some of the details he adds are probably not to be trusted. For example, in his account of the creation myth, he suggests a kind of volcanic eruption from Muspelheim led to the creation of life. But there are no volcanoes in the traditional Norse and German territories where the myth originates. There are plenty in Iceland.

Similarly, after the destruction of the world at Ragnarok when the world sinks back into the waters of chaos, it is only Sturluson who suggests that the world reemerges and that a few gods and men go on to repopulate. This seems to align with the Christian ideology of God promising to rebuild the world after the great flood. These are just a few examples of details that don’t survive anywhere else and seem like they could have been invented by Sturluson.

Heimskringla

The Heimskringla is named for the first two words that appear in the manuscript—Kringla heimsins—which means circle of the world. The manuscript tells the stories of Swedish and Norwegian kings, no doubt to gratify Sturluson’s patrons in the Norwegian royal family.

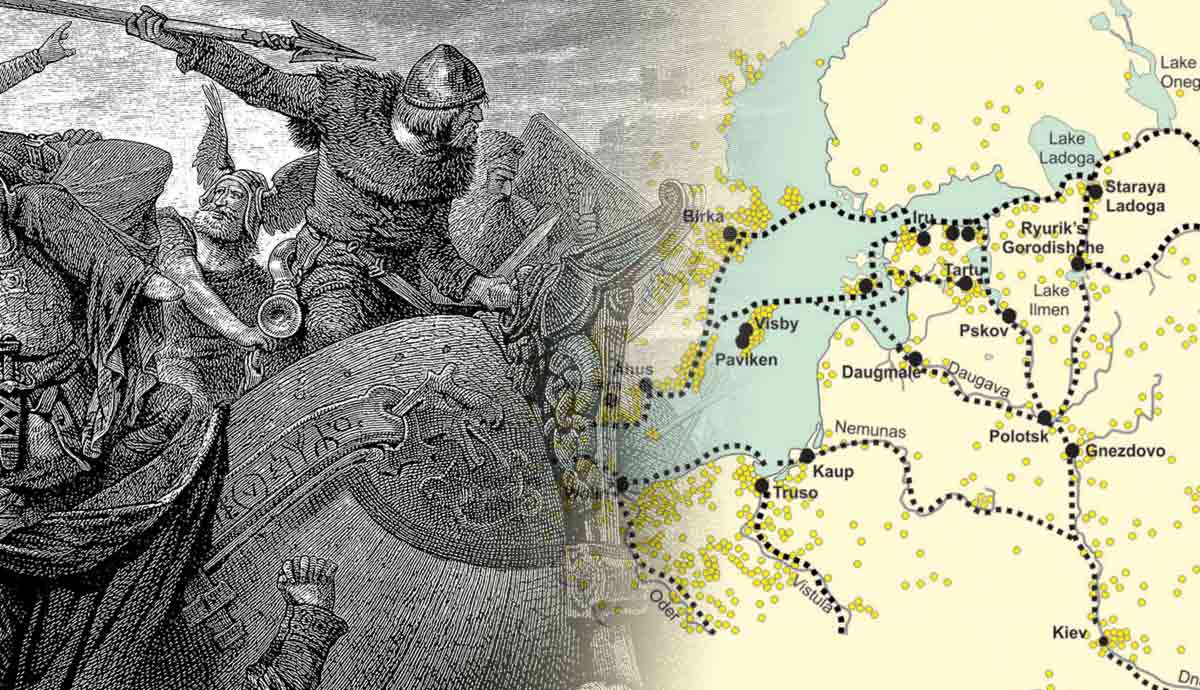

He starts with the legendary Ynglings dynasty of Sweden and then tells the stories of historical Norwegian rulers from Harald Fairhair, who united Norway, to Eystein Meylar, who died two years before Sturluson was born.

Again, some sections are more reliable than others. He seems to have based the work on existing sagas, short histories, and oral traditions, again filling in the blanks where there are gaps. It starts with legends, with the first kings being descendants of the god Freyr, and becomes more historical as it moves closer to Sturluson’s own day.

His characters are larger than life, defeating 100 men single-handedly in battle, and there are elements of myth as they encounter witches and seeresses. Nevertheless, modern scholars agree that the world Sturluson describes offers valuable information about what Norway and Iceland were like in the 12th and 13th centuries.