Apartheid in South Africa stripped nonwhites of their dignity. It was the tool of a brutal regime that committed many atrocities to maintain its grip on the power structures of the country. Mentally and physically, black people were reduced to the position of low-class labor with no opportunities for a better life. The African National Congress and the Pan-Africanist Congress struggled to keep a visible profile as their organizations were banned. To wage a guerilla war, they needed to hide from plain sight. The onslaught of apartheid left many of the struggle icons dead or languishing in prison cells, unable to reach the masses they represented. In order to remedy this state of affairs for black people, a student leader and anti-apartheid activist named Steve Biko founded the Black Consciousness Movement to mobilize and empower the urban black population.

Steve Biko’s Early Life

Bantu Stephen Biko was born on December 18, 1946 in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. His father worked as a clerk in the King William’s Town Native Affairs Office, and his mother worked as a domestic, cleaning the houses of local white people, then as a cook at a hospital. The way his mother was treated and her harsh living conditions are likely what started Steve Biko’s political consciousness.

When he was at school with his brother Khaya, the latter was accused of having ties to Poqo, the armed wing of the Pan-Africanist Congress. Both Steve and Khaya were arrested, and Khaya was charged but later acquitted. No evidence was presented, but the scandal damaged the school’s reputation, and Khaya was expelled. As a result, Steve developed a deep hatred for authority.

Steve Biko grew to be a tall and slim man. According to his friend, Donald Woods, Biko was over 6 feet tall and had the build of a heavyweight boxer. His friends considered him to be handsome and quick-witted.

University Days

When he finished matric (last year of school in South Africa), Steve Biko enrolled in the University of Natal, where he studied for a medical degree. The University of Natal, situated in the port city of Durban, had become a hub of intellectual discourse that had attracted a number of black academics who had been stripped of their former posts by the University Act of 1959. Biko thus found himself amid a movement characterized by a political discourse focused on civil rights.

Biko was elected head of the Students’ Representative Council, which was affiliated with the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS). Although NUSAS had endeavored to be multi-racial, it was still a predominantly white organization, as white people formed the majority of the students in South Africa. The problem with this was that NUSAS was founded on white initiative and with white money and reflected the hopes and desires of white people (even if they were liberal).

Seeking their own union, many of the black members of NUSAS formed their own union that sought to improve relations with centers of black student activity. The South African Students’ organization was born, and although Steve Biko tried to keep a low profile, he was elected its first president.

In the early 1970s, as president of SASO, Biko developed the idea of Black Consciousness in collaboration with other student leaders in the organization. This focused on the idea of psychological improvement for black people in South Africa, stressing that black people should not be made to feel inferior and that no black person should be considered a foreigner in their own country. The term “black” included all non-whites and was used as a term instead of “non-whites” in order to solidify an identity opposed to the white minority.

Biko drew influence from many sources and adapted them to fit the South African context. Among those who influenced Biko’s ideology were Malcolm X, Frantz Fanon, Paulo Freire, James H. Cone, and Léopold Sédar Senghor. Biko also drew inspiration from Black Power movements in the United States, as well as anti-imperialist and Marxist ideologies.

SASO later split from NUSAS. Many white students felt spurned by the move as they were committed to a multi-racial organization. NUSAS, however, decided not to criticize SASO, as their ultimate goals were the same, and it would pit white students against black students and play into the apartheid government’s hands. The government, however, did see the split as a victory in that it could be spun as an instance of separate development–one of the main goals of apartheid.

White liberalism was an early target of Steve Biko’s Black Consciousness Movement. In one of his earlier articles, Biko accused white liberals of “paternalism” towards black people and suggested that their attitude towards multi-racialism was to appease their own conscience. Meanwhile, SASO was increasingly disrupting the status quo. In May 1972, the organization called for students to boycott lectures over the expulsion of Abram Onkgopotse Tiro, who was expelled for his speech criticizing the administration of the University of the North.

In 1970, Steve Biko married Nontsikelelo “Ntsiki” Mashalaba, and the two became parents to a son, Nkosinathi, in 1971. Due to his focus on political activism, Biko’s grades declined, and in 1972, he was barred from further study at the University of Natal. Steve and Ntsiki would go on to have another child, Samora, but the marriage was not a happy one. Biko’s serial adultery would lead Ntsiki to move out of the house and file for divorce. Biko had three other children through extramarital affairs.

Biko’s Trouble With the Government

In the early 1970s, the Black Consciousness Movement grew in strength, reach, and scope. By 1973, the apartheid government considered the BCM a threat, and a “banning order” was placed on Steve Biko. This was an extrajudicial measure used by the South African government to limit the activities of those it saw as political opponents. This restricted Biko from officially being involved in Black Community Projects, which had been a significant factor in Biko’s attempt to bring services to and unite black people. Nevertheless, Biko found workarounds to the issue and continued his support where he could.

During the time of his banning order, Biko met with Donald Woods, the editor of a newspaper, the Daily Dispatch, which was a publication highly critical of the apartheid regime. Biko tried to convince Woods to publish more coverage of the BCM, and after an initial reticence, Woods agreed. Biko and Woods developed a close friendship. Biko also developed a close friendship with another white liberal, Duncan Innes, who had been the NUSAS president in 1969. These friendships drew criticism from many in the BCM movement as they felt it was a betrayal of BCM attitudes towards black liberation.

In August 1977, there was growing dissension in the Cape Town chapter of the BCM. Steve Biko decided to handle the matters personally and drove to Cape Town with a friend, Peter Jones. Upon arrival in Cape Town, the leader of the Unity Movement there refused to speak with Biko. Having no alternative but to return the way they came, Biko and Jones drove back towards King William’s Town in the Eastern Cape.

On August 18, on the way to King William’s Town, they were stopped at a roadblock and arrested. Biko was taken to a police station in the city of Port Elizabeth, where he was kept shackled and naked. From there, he was transferred to a room run by the security services in a building in central Port Elizabeth. Again, shackled to the wall and forced to stand, he was beaten and interrogated for 22 hours. Steve Biko suffered extensive damage to his head and died from a brain hemorrhage on September 6.

Peter Jones was held without trial for 533 days and was frequently interrogated.

In the Wake of Steve Biko’s Death

The death of Steve Biko drew widespread condemnation, not just from within South Africa but in many parts of the world. Twenty thousand people attended his funeral, including foreign diplomats from 13 countries. Biko’s funeral signified a mass political protest and prompted the government to ban the Black Consciousness Movement, along with many of its symbols. Among international criticism, the apartheid government held a sham inquest to investigate Biko’s death and concluded that he had hit his head on a cell wall during a scuffle. The international community viewed this verdict with extreme skepticism.

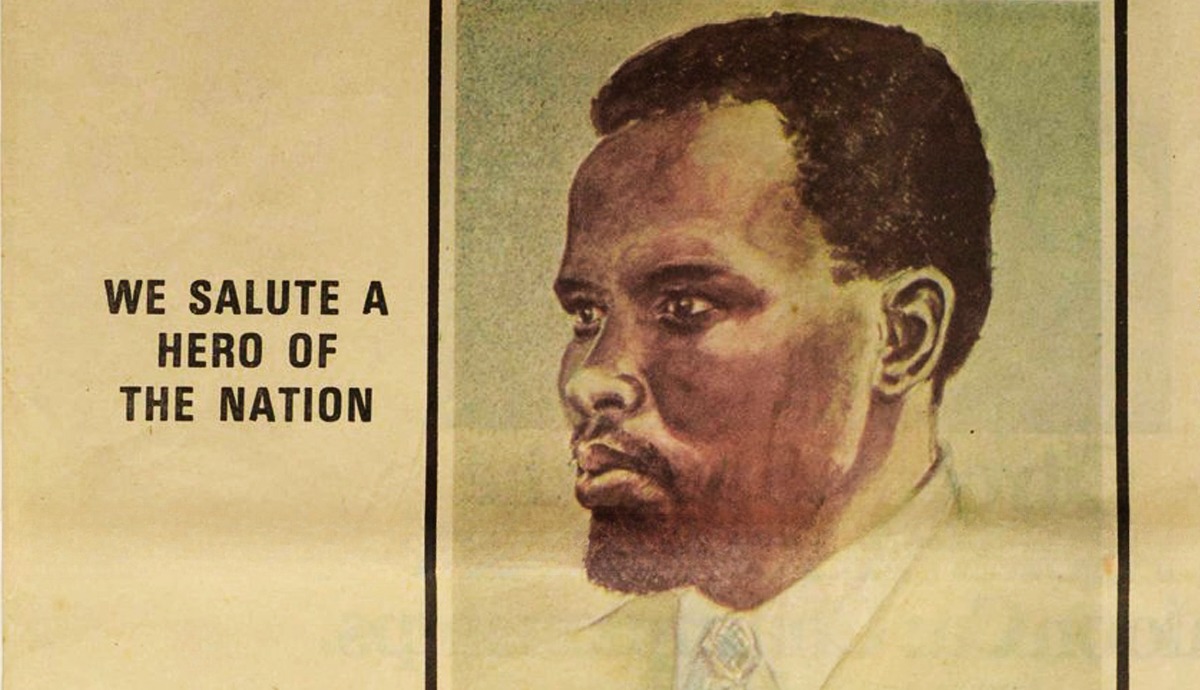

Steve Biko’s Legacy

Nelson Mandela called Steve Biko “the spark that lit a veld fire across South Africa.” While the struggle icons such as Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Ahmed Kathrada, and Govan Mbeki were all languishing in their prison cells on Robben Island, Steve Biko was a visible and audible force that reinvigorated the struggle against apartheid.

After Biko’s death, his fame increased, and his ideas lived on, spawning more political movements such as AZAPO to fight against the apartheid regime. His writings were published even more, and international pressure on the South African government increased.

Today, Steve Biko is remembered as one of the most important heroes in the fight against apartheid. Many places are named after him in South Africa and around the world, and his name is still invoked by those fighting for equality and justice.