The Samaritans were a group of people who inhabited the region of Samaria in ancient Israel. One theory claims their origins can be traced back to the Assyrian conquest of the northern kingdom of Israel in the 8th century BCE. The Samaritans themselves lay claim to much older origins and what they believe is a purer form of Abrahamic religion. Yet another theory claims that a schism between the Jews and the Samaritans occurred during the Hellenistic and Roman periods. So, let us consider the theories and gain insight into who the Samaritans during the time of Jesus were.

Samaritans in the Bible

In the Protestant canon, the word “Samaritans” appears only once in the Old Testament. This instance seems to refer to the ten tribes of Israel that constituted the Northern Kingdom of Israel as Samaritans. Contextually it speaks to the Assyrian conquest of the Northern kingdom that exiled its people.

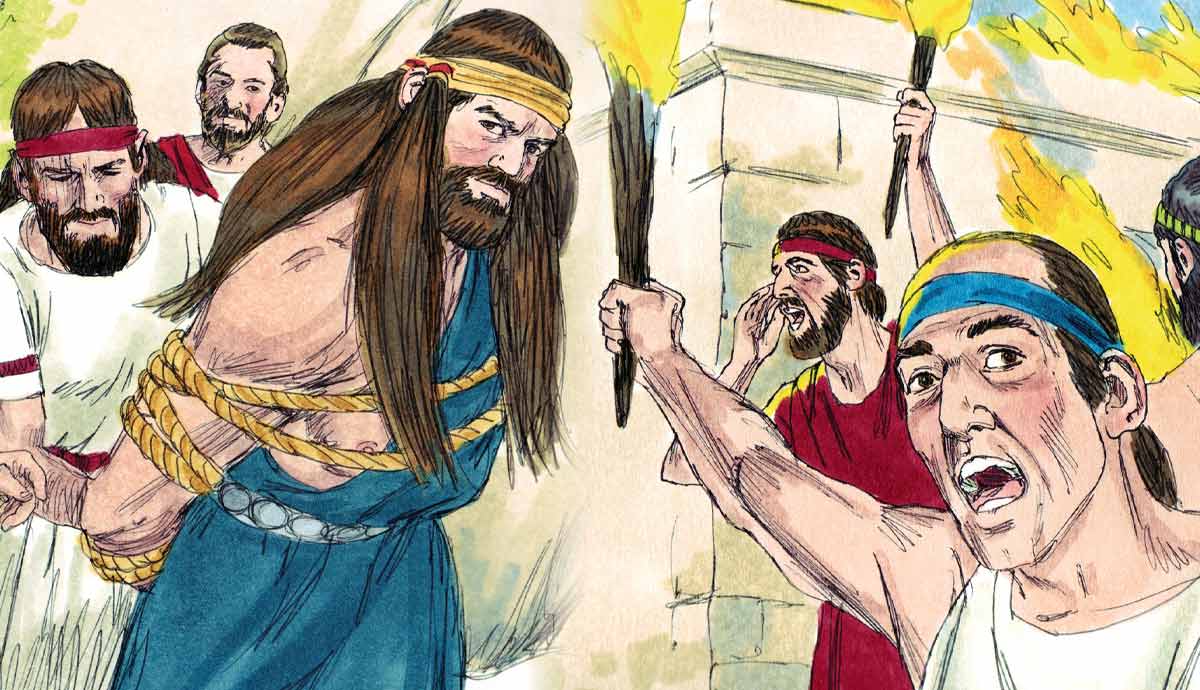

The Assyrians brought people from different parts of their domain to settle in Samaria. These groups eventually intermarried with the remnant of the Israelites who did not go into exile. According to the Biblical narrative, God sent lions among them who killed some of the residents. The Assyrian king then decreed that one of the priests they sent into exile must return to teach the residents “the law of the god of the land” (2 Kings 17:29) so that they could avert the killings. The people continued to worship their gods alongside the Israelite practices they learned from the priest. Idolatry continued at the high places in the Northern Kingdom.

The New Testament refers to the Samaritans on several occasions. The tension between the Jews and the Samaritans is evident in the text (John 4:9), though Samaritans often portray the role of the person who does the right thing in a particular situation (Luke 10; Luke 17), rather than the Jews, which must have irked the Jewish audiences.

Jesus, however, did not recognize the claimed Israelite heritage of the Samaritans when he sent the twelve to minister among the Jews. He said: “Go nowhere among the Gentiles and enter no town of the Samaritans but go rather to the lost sheep of the house of Israel” (Matthew 10:5-6).

Origins of the Samaritans

There are several theories about the origins of the Samaritans. The first is their own narrative, claiming they are the true descendants of Israel. They draw their lineage from the tribe of Joseph through his sons Ephraim and Manasseh, and they have remained faithful to the Torah, or Law of Moses. Their priests are from the tribe of Levi, descended from the line of Aaron. They follow the same history the Bible narrates, with Joshua building a tabernacle at Gerizim.

The Samaritan version of events diverges from the biblical narrative around the time of Eli. They claim Eli (a descendant of Ithamar) usurped the high priesthood from Uzzi (a descendant of Eleazar), the legitimate high priest. Eli and Samuel learned witchcraft and magic from foreigners who moved into Northern Israel and established a cult of false worship in Shiloh, setting up a rival tabernacle and priesthood. When Samuel anointed Saul as king, he went to Shechem, destroyed the remaining altar at Gerizim, and killed the High Priest Shisha, son of Uzzi.

David went to Shechem to take up his crown, but when he wanted to build the Temple in Jerusalem, the new High Priest, Yaire, told him it should be built there, on Mount Gerizim. David then left the construction to his son Solomon, who followed the false system and built the Temple in Jerusalem.

Later, Solomon supported the false system set up by Eli and Samuel, which became the basis for the Temple worship in Jerusalem. During the exile many centuries later, Cyrus allowed Abdullah, a Samarian priest, to return and build a temple in Gerizim, but through bribes and witchcraft, Zerubbabel and Ezra managed to sway the kings of the Persians to have the Temple in Jerusalem reconstructed.

The Samaritans believe that the Torah they have is the original, unchanged version, while the cult among the Jews is a corrupted version. They view themselves as keepers of the Law and the legitimate line of Israelite worship.

Samaritan Origins From a Jewish Perspective

The Assyrians invaded the Northern Kingdom and captured the capital, Samaria, in 722 BCE. They sent some citizens into exile but left a significant number behind. The historical record confirms this in an inscription on the walls of the palace at Dur-Sharrukin where Sargon II, the king of Assyria, says: “In my first year … I carried away the people of Samaria … to the number of 27,290 … the city I rebuilt. I made it greater than it was before.” He resettled people from other parts of the Assyrian Empire in the conquered territory of the Northern Kingdom. In time, people from the various nations that occupied the land intermarried, and the result was a mixture of cultures and religious practices. The Jews called the people from that region Samaritans.

The Jews viewed the Samaritans as descendants of apostate Israelites who had abandoned their true faith by intermarrying with foreigners and adopting foreign religious practices. This perception was reinforced by the Samaritan rejection of the centralization of worship in Jerusalem and by their adherence to a different version of the Torah. Their establishment of an alternative center of worship around Mount Gerizim in Samaria irked the Jews, who did not consider the people who amalgamated with foreign people and incorporated foreign styles of worship as part of Israel.

The Jews and Samaritans viewed each other with equal skepticism and disdain. Each believed the other had apostatized and distorted the true worship of Yahweh. The way the Jews dealt with the Samaritans was to avoid communicating with them or having any dealings with them as far as possible. The conversation Jesus has with a Samaritan woman at the well reflects this. When Jesus spoke with her, she said: “How is it that you, a Jew, ask for a drink from me, a woman of Samaria?” The text then explains that the “Jews have no dealings with Samaritans” (John 4:9). Shortly after, their conversation reflects the theological differences between the Jews and the Samaritans.

The Samaritan says: “Sir, I perceive that you are a prophet. Our fathers worshiped on this mountain, but you say that Jerusalem is the place where people ought to worship.” Jesus replies to her, “Woman, believe me, the hour is coming when neither on this mountain nor in Jerusalem will you worship the Father. You worship what you do not know; we worship what we know, for salvation is from the Jews. But the hour is coming and is now here when the true worshipers will worship the Father in spirit and truth, for the Father is seeking such people to worship him. God is spirit, and those who worship him must worship in spirit and truth.”

The difference in views on where to worship became the subject of conversation. The attitude Jesus displayed toward the woman at the well and in his parables reflected a different way of dealing with them. Though he did not see them as part of Israel, he did not shun them. Jesus engaged with this woman, reflecting an attitude that transcends national affiliation. He had a similar way of dealing with Gentiles as well. To Jesus, the Samaritans were not opponents but a field for ministry.

The dislike the Jews had of the Samaritans is reflected in the charge the Jews made against Jesus. They accused him of being possessed by a demon and being a Samaritan (John 8:48). They wanted the disdain the Jews had for the Samaritans to influence the views of those who heard the charges against Jesus. This bias would identify Jesus as someone they should treat with contempt.

A Third View

Some scholars believe the schism between the Jews and Samaritans developed much later. According to this view, the divide happened gradually. It started during the Hellenistic Period, possibly lasting into the Roman Period. Proponents of this view describe the separation as a response to changing political and social circumstances under different occupations rather than a single event. A much more complex and diverse set of influences—political, social, cultural, and ideological—shaped the path of the Samaritan people.

These scholars base their argument on archaeological and textual evidence suggesting that shared religious practices, beliefs, and cultural exchanges among various regional groups led to a more gradual divergence.

Samaritans: Conclusion

There are three primary theories about the origin of the Samaritans. The first is their own narrative according to which they are the pure line of Israelites through Joseph and his sons. They set up worship on Mount Gerizim and have an uncorrupted version of the Torah. The second is the Jewish view, which sees the Samaritans as a mixture of the remnants of the kingdom of Israel and other nations. They believe that the religion of the Samaritans was contaminated by foreign influence. The last is the view that a much later separation between the two groups took place over an extended period.

Whichever view is correct, in Biblical times the contempt between the Jews and the Samaritans was palpable. Though Jesus did not regard them as remnants of Israel, he did reach out to them during his personal ministry.