The age of the diadochi of Alexander the Great was one of the bloodiest pages of Greek history. A series of ambitious generals attempted to secure parts of Alexander’s empire, leading to the creation of the kingdoms that shaped the Hellenistic World. This was a period of intrigue, treachery, and blood.

The Death of Alexander the Great

Alexander the Great died on June 11, 323 BCE, in Babylon, possibly from typhoid fever. Before taking his last breath, Alexander was asked by his generals to whom the empire would go. With his final strength, he said, “to the strongest.”

Alexander left behind him the greatest empire the ancient world had ever seen. This vast empire contained lands from the Adriatic Sea all the way to the Indus River, and from Libya to modern-day Tajikistan. Of course, Alexander had just recently conquered these lands and a great part of this empire was not firmly secured.

The main problem with Alexander’s death was that it was sudden and early. The Macedonian general had not spent enough time consolidating his rule. As a result, there was no man ready to succeed him yet. His sudden passing away also meant that the empire would soon fall into shock.

From 323 to 281, a series of wars took place between Macedonian generals. These bloody wars are also called the Diadochi wars from the Greek word ‘diadochos’, which means successor. The most important diadochi who emerged during this time were the following:

Timeline of the Wars of the Diadochi

| Year(s) | Phase / Event | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 323 BCE | Death of Alexander; Partition of Babylon | Power-sharing proves unstable and sparks the Successor conflicts. |

| 322–320 BCE | First War of the Diadochi (Perdiccan War) | Partition of Triparadeisus (321) reassigns satrapies; Antipater becomes regent. |

| 318–316 BCE | Second War of the Diadochi | Antigonus dominant in Asia. |

| 315–311 BCE | Third War of the Diadochi | Peace of 311; uneasy truce sets stage for renewed conflict. |

| 311–309 BCE | Babylonian War | Birth of the Seleucid Empire; Antigonid hopes of reunification fade. |

| 307–301 BCE | Fourth War of the Diadochi | Climax at Ipsus (301): Antigonus killed; coalition victory reshapes the map. |

| 298–285 BCE | Struggle over Macedon | Macedonian crown changes hands; balance among the dynasties hardens. |

| 285–281 BCE | Final Successor Showdown | Corupedium (281): Seleucus defeats and kills Lysimachus; weeks later Seleucus is assassinated by Ptolemy Ceraunus. Conventional end of the Diadochi wars. |

The Wars of the Diadochi

After Alexander’s passing, his most important generals and guards gathered to discuss the future of the empire. It was agreed that the successor would either be one of the two:

- Alexander’s yet unborn child by his wife Roxana (if it were a boy).

- Alexander’s brother-in-law Philipp III.

Alexander’s son was eventually born and named Alexander IV. Perdiccas took on the role of the empire’s regent until the boy could grow enough to rule.

Perdiccas was the most legitimate to hold the position of regent. Before passing away, Alexander the Great had given his ring to the general, designating him responsible for the empire. Even though no one doubted Perdiccas openly, everyone was suspicious of Perdiccas, and Perdiccas was suspicious of everyone.

The balance of power changed soon as Perdiccas was murdered in 321 BCE. Shortly before, Ptolemy had managed to take Egypt for himself and secretly transport Alexander’s body to Alexandria which was under his control. This way, Ptolemy secured one of the empire’s richest and most prestigious parts.

From Triparadisus to the Battle of Ipsus

After Perdiccas’ death, the diadochi gathered in Triparadisus at 321 BCE to partition the empire. The partition showed that the diadochi were having their own ambitions, but the empire was still united under the names of Alexander IV and Philip III. After Triparadisus, Antipater replaced Perdiccas as the empire’s regent. However, he died in 319 BCE from old age (81 years old).

The next decades were a long and bloody conflict amongst the Diadochi. The dominant figure of the years between 320-301 BCE was, without a doubt, Antigonus. While the rest of the Diadochi had given up on the dream of a grand Macedonian empire, Antigonus still believed that Alexander’s conquests could remain united under his name. Antigonus was having a lot of success and kept growing his domain to become the most formidable power between 320-301 BCE.

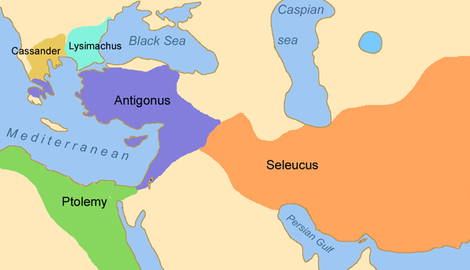

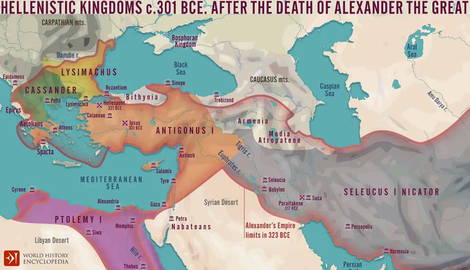

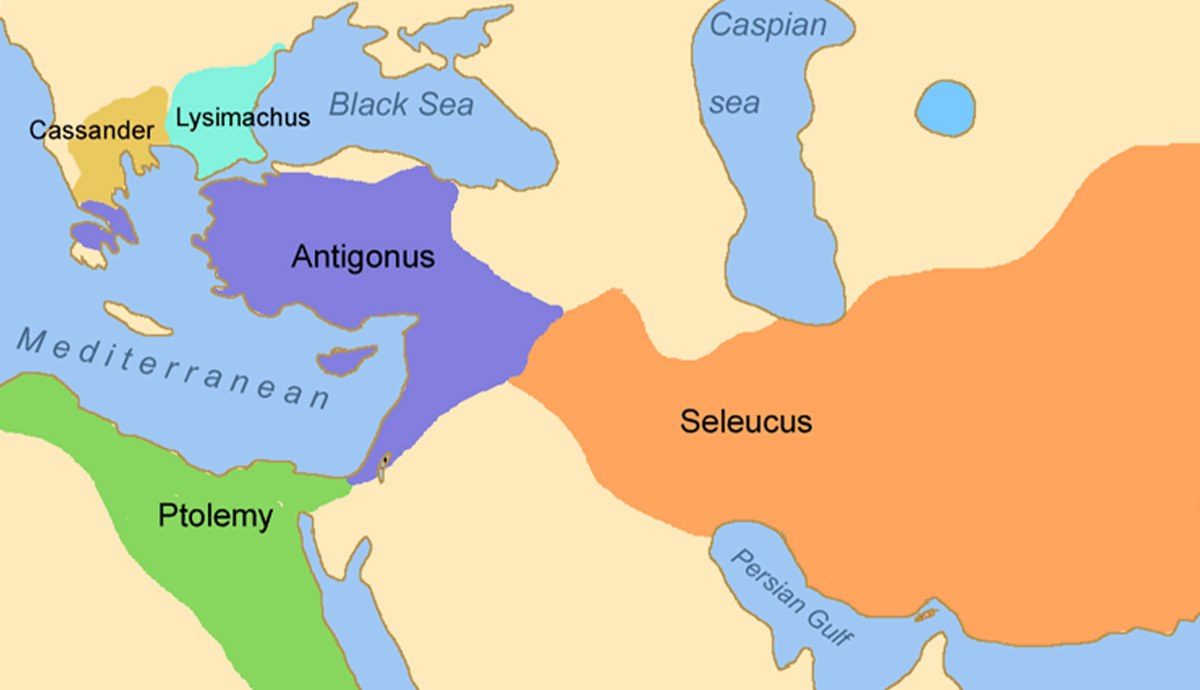

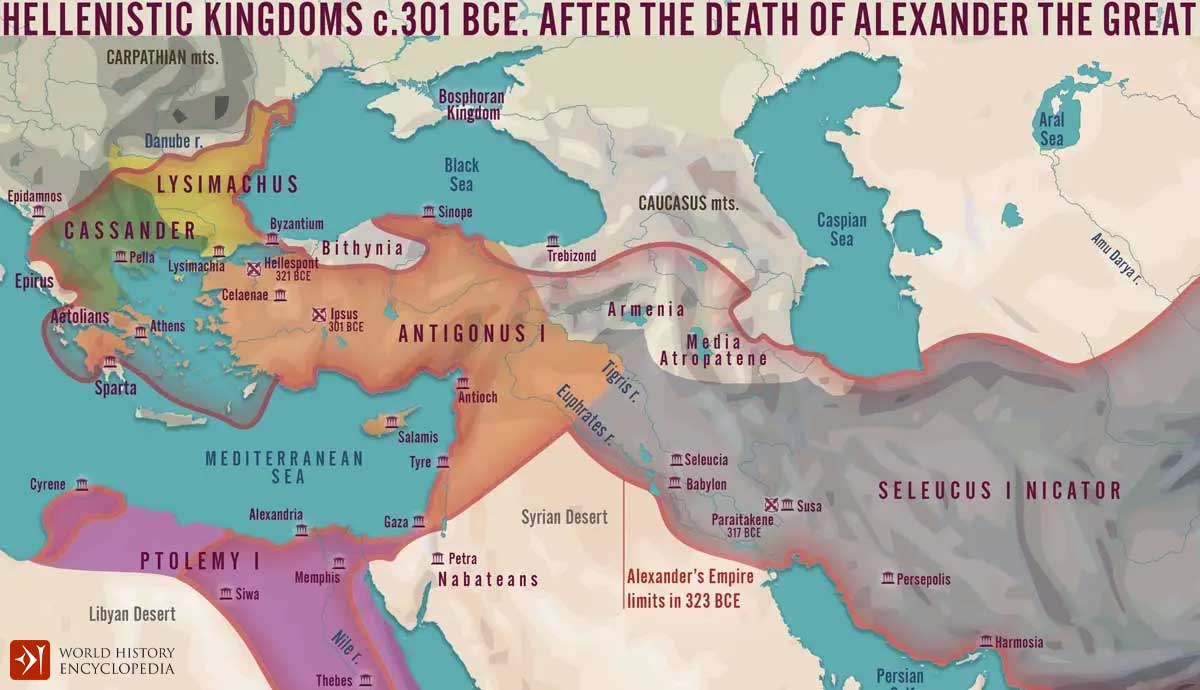

As ambitious successors were being eliminated one by one, Cassander assassinated Alexander IV in 311 BCE. delivering the final blow to Alexander’s bloodline. Before the assassination, the greatest Diadochi of the time had signed a peace treaty recognizing the status quo of four separate kingdoms; Ptolemy in Egypt, Antigonus in the whole of Asia, Cassander in Europe (Macedonia and Thessaly), and Lysimachus in Thrace. Seleucus was left out of the treaty but maintained Babylon of which he was the satrap.

In 301, the allied forces of Cassander, Lysimachus, and Seleucus fought against Antigonus and his son Demetrius I Gonatas in Ipsus of Phrygia. The battle of Ipsus was decisive for the future of the Hellenistic world. Antigonus died and his son Demetrius fled. Lysimachus expanded his realm to include Asia Minor and Ptolemy added to his realm the lands of Southern Syria.

After Ipsus

The aftermath of Ipsus, the greatest battle of the Diadochi wars, was immense. Antigonus, the last successor believing in the empire’s unity, was dead. Furthermore, Ipsus signified the final division between Europe and Asia, which would follow separate fates.

As Cassander died of dropsy in 297 BCE, Demetrius attempted to take the lands of Cassander, mainly Macedonia, for himself. However, he lost battle after battle and was captured by Seleucus in 285 BCE.

Lysimachus kept growing. At some point, he was firmly in charge of Thrace, Macedonia, and a good part of Asia Minor, but was also defeated and killed by Seleucus in the battle of Kouropedion in 281 BCE. After this battle, Seleucus took the Asian lands of Lysimachus and prepared to invade Europe and return to his homeland, Macedonia. Then, unexpectedly, he was assassinated by his ally, Ptolemy Keraunos, a son of Ptolemy who had allied himself with Seleucus.

Antigonus II Gonatas, the grandson of Antigonus and the son of Demetrius, took advantage of the anarchy that followed the deaths of Seleucus and Lysimachus and managed to become king of Thessaly and Macedonia in 276 BCE. This way, Antigonus secured the last unassigned area left in the Empire.

This was the end of the wars of the Diadochi. The Hellenistic World was set for the next few hundred years until the coming of Rome. The Antigonids would rule Macedonia, the Ptolemies Egypt, and the Seleucids Syria, Mesopotamia, and Iran.

List of the Diadochi & Their Main Territories

| Diadochus | Main territories after 323 BCE | Ruled / Active (approx.) | Fate (year) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perdiccas | Imperial regency (empire-wide authority) | 323–321 BCE | Assassinated by officers (321 BCE) |

| Antipater | Macedonia & Greece | 321–319 BCE | Died of old age (319 BCE) |

| Cassander | Macedonia, Thessaly, southern Greece | de facto 317–297; king 305–297 BCE | Died of dropsy (297 BCE) |

| Lysimachus | Thrace; after 301, much of Asia Minor; later Macedonia | 306–281 BCE | Killed at Corupedium vs. Seleucus (281 BCE) |

| Ptolemy I Soter | Egypt, Cyrenaica, Cyprus; parts of Syria at times | satrap 323–305; king 305–283/2 BCE | Died (winter 283/282 BCE) |

| Seleucus I Nicator | Babylonia, Syria, Mesopotamia, Iran; later Asia Minor | 305–281 BCE | Assassinated by Ptolemy Ceraunus (281 BCE) |

| Antigonus I Monophthalmus | Asia Minor, Syria, Mesopotamia (at peak) | 306–301 BCE | Killed at Ipsus (301 BCE) |

| Demetrius I Poliorcetes | Parts of Greece/Asia; later Macedon | 294–288 BCE (king); active 312–283 | Dies in Seleucid captivity (283 BCE) |

| Eumenes of Cardia | Asia Minor (for royal cause) | 323–316 BCE | Executed by Antigonus (316 BCE) |

| Craterus | — (killed early in the wars) | 323–321 BCE | Killed in battle (321 BCE) |

| Polyperchon | Macedonia & Greece (as regent); later Peloponnese strongholds | Regent 319–317 BCE; active until early 3rd c. BCE | Last securely attested 303 BCE; death unknown |

| Alexander IV | Nominal kingship over Macedon & empire (under regency) | 323–310/309 BCE | Murdered with Roxana (310/309 BCE) |

| Philip III Arrhidaeus | Nominal kingship over Macedon & empire (under regency) | 323–317 BCE | Executed by Olympias (317 BCE) |

The Diadochi Who Founded the Three Great Hellenistic Dynasties

As we saw, the great dynasties that emerged after Alexander’s death were the Ptolemies, the Seleucids, and the Antigonids. The first two were established by the original Diadochi, who had served in Alexander’s army. Only the Antigonids were established by Antigonus II Gonatas, the grandson of the original Diadochos, Antigonus I Monophthalmos.

1. Ptolemy I Soter

Ptolemy I Soter had served under Alexander the Great as one of his bodyguards and most trusted advisors. He had also accompanied the Macedonian king in his visit to the oracle in the Oasis of Siwa.

After Alexander’s death, Ptolemy became the satrap of Egypt during the rule of Alexander IV and Philip III.

In 321, Perdikkas was moving Alexander’s body to Macedon, where the great general would be buried. However, Ptolemy managed to trick everyone and stole Alexander’s body, bringing it first to Memphis and then to Alexandria. There, Ptolemy constructed a luxurious tomb where Alexander was worshiped as a god. This way, Ptolemy secured legitimacy for his rule over Egypt, as Alexander was the previous ruler holding the title of pharaoh.

Ptolemy fought in the wars of the Diadochi, expanding his realm with Cyprus, Cyrenaica, and Judea. He had lots of children and became a great patron of the arts and letters. He built the library and museum of Alexandria and made the city the center of Hellenism.

Ptolemy died at the age of 85 in 282 BCE. He was leaving behind a stable kingdom with a line that would rule until 30 BCE when his last successor, Cleopatra, died and the kingdom was absorbed by Rome.

2. Seleucus I Nicator

Seleucus had fought next to Alexander as he conquered Asia and rose to become the commander of the Hypaspistai, an elite military unit. After Alexander’s death, Seleucus did not initially obtain a position of great power. However, he did become a chiliarch and was positioned close to the strongest man of the empire, Perdiccas. Seleucus took part in the assassination of Perdiccas and, for this service, was awarded the satrapy of Babylon.

As a satrap, he faced a lot of problems with the natives, but he managed to maintain some order in the city until 316 BCE. On this date, Seleucus punished one of the soldiers of Antigonus who had visited Babylon. Since Seleucus had not asked for permission to carry out this act, Antigonus asked for some monetary retribution. Seleucus refused and fled to Egypt.

In Egypt, Seleucus helped coordinate the other diadochi against Antigonus, who was now the strongest diadochos, and fought under Ptolemy as an admiral in the ensuing war for domination in the Aegean Sea. Once he saw an opening, he got a company of a few men and reclaimed Babylon, thus establishing his dynasty, the Seleucids.

From that point on and until 302, Seleucus kept expanding his territory. He took advantage of Antigonus’ wars against Ptolemy, Lysimachus, and Cassander and brought the eastern part of the empire, including India, under his control. Between 311 and 309, Seleucus fought against Antigonus in the so-called Babylonian war, solidifying his border in Syria. He then focused his attention eastward,s fighting against the Mauryan empire. The end of this conflict saw him earn 500 war elephants and solidify his eastern border.

The 500 elephants proved detrimental in the battle of Ipsus in 301 BCE. After Antigonus’ death, Seleucus had secured his place in Asia. In the years after Ipsus, Seleucus cemented his rule and established a long-lasting dynasty. He founded a series of cities, the most important of which were Seleucia Pieria, Laodicea in Syria, Antioch, and Apameia on the Orontes River. In total, he founded nine cities called Seleucia, sixteen called Antioch, and six called Laodicia.

Seleucus had just defeated Lysimachus and was about to invade Macedonia, where he hoped to spend his last days, when he was assassinated by his ally, Ptolemy Keraunos, in 281 BC. He was succeeded by his son Antiochus I. The kingdom of the Seleucids would last until 63 BCE when it was conquered by the Roman Empire.

3. Antigonus I Monopthalmus

Antigonus had served under Philip II and took part in Alexander the Great’s conquest of the Achaemenid Empire. Alexander respected his experience and placed him as a commander of a large part of his army.

After the great battle of Issus in 333 BCE, Antigonus fought remnants of the Persian army and was left behind by Alexander to secure Phrygia. When Alexander died, Antigonus maintained his influence over Phrygia and kept expanding his domain until he became the strategos (general) of Asia after Perdiccas’ death and under Antipater’s regency.

During the next decades, Antigonus proved the most ambitious and powerful of the Diadochi. He took Babylon from Seleucus and kept fighting for influence over Asia, the Aegean, and Greece. At the same time his son, Demetrius, was evolving into a great general. Antigonus was the only one actively seeking to reunite Alexander’s empire.

Seeing his power growing, the other Macedonian generals formed a coalition against him. In 314 BCE, Cassander, Lysimachus, Ptolemy, and Seleucus moved against Antigonus. The ensuing war was chaotic. Its aftermath saw Antigonus reaching the peak of his power while at the same time recognizing that Seleucus would from now on take the Eastern part of Asia from Babylon all the way to the Indus River.

In 311 Antigonus controlled Greece, Asia Minor, Syria, Phoenicia, and a great part of Mesopotamia. After this period, Antigonus kept fighting against the remaining dynasts and quite often against all of them at the same time. The war between the Diadochi continued until the battle of Ipsus in 301 BCE. There Antigonus lost his life and Demetrius, who was now called the Poliorcetes for the novel siege methods he used during the siege Rhodes in 302 BCE, fled.

The Legacy of Antigonus

In the ensuing years, Demetrius conquered the kingdom of Macedonia only to be captured by Seleucus a few years later. Finally, Demetrius’ son, Antigonus II Gonatas, took back Macedonia from the son of Cassander and established the permanency of the Antigonid bloodline in the area. The Antigonids would remain in power until the coming of the Romans in 168 BCE.

The Diadochi That Failed to Establish a Dynasty

Starting with Perdiccas, the empire’s first regent, and Antipater, its second one, there is a long series of Diadochi who did not manage to establish their own dynasty and secure the lastingness of their bloodline.

As we saw, Perdiccas was assassinated in 321 BCE. Antipater, however, died of old age in 319 BCE. Paradoxically, he did not appoint his son, Cassander, as his successor but Polyperchon, an officer who took Macedon under his control and kept fighting for the dominance of the area until the early 3rd century.

Alexander the Great’s son, Alexander IV, died in 309 BC at the age of 14, assassinated by Cassander. However, until his death, Alexander IV was considered the legitimate successor of Alexander, although he never exerted any real power.

Philip III Arrhidaeus was the brother of Alexander the Great. However, he suffered from severe mental health issues that never allowed him to rule. Philip was initially destined to be a co-ruler of Alexander IV. He married Eurydice, a daughter of Cynane who was a daughter of Philip II, Alexander the Great’s father. Eurydice was extremely ambitious and sought to expand Philip’s power. However, in 317 BCE Philip and Eurydice found themselves in a war against the mother of Alexander the Great, Olympias. Olympias captured them, murdered Philip, and forced Eurydice to commit suicide.

Cassander

Cassander, Antipater’s son, was notorious for murdering Alexander’s wife, Roxana, and only successor, Alexander IV, as well as his illegitimate son Heracles. He also ordered the death of Olympias, Alexander’s mother.

Cassander married Alexander’s sister Thessalonica to strengthen his royal claim as he fought mainly for Greece and the kingdom of Macedonia. Eventually, he became the king of Macedonia from 305 until 297 BCE when he died of dropsy. His children Philip, Alexander, and Antipater proved incapable heirs and did not manage to maintain the kingdom of their father which soon passed to the hands of the Antigonids.

Cassander founded important cities like Thessalonica and Cassandreia. He also rebuilt Thebes, which had been razed to the ground by Alexander.

Lysimachus

Lysimachus was a very good friend of Philip II, Alexander’s father. He later became a bodyguard of Alexander during his campaign against the Achaemenid Empire. He founded the city of Lysimachia.

After Alexander’s death, Lysimachus ruled Thrace. In the aftermath of the battle of Ipsus, he expanded his territory, which now included Thrace, the north part of Asia Minor, Lydia, Ionia, and Phrygia.

Towards the end of his life, his third wife, Arsinoe II, who wanted to secure the succession of her own son on the throne, forced Lysimachus to kill his firstborn son, Agathocles. This murder caused Lysimachus’ subjects to revolt. Seleucus took advantage of the situation, invaded and killed Lysimachus at the battle of Kouropedium in 281 BCE.