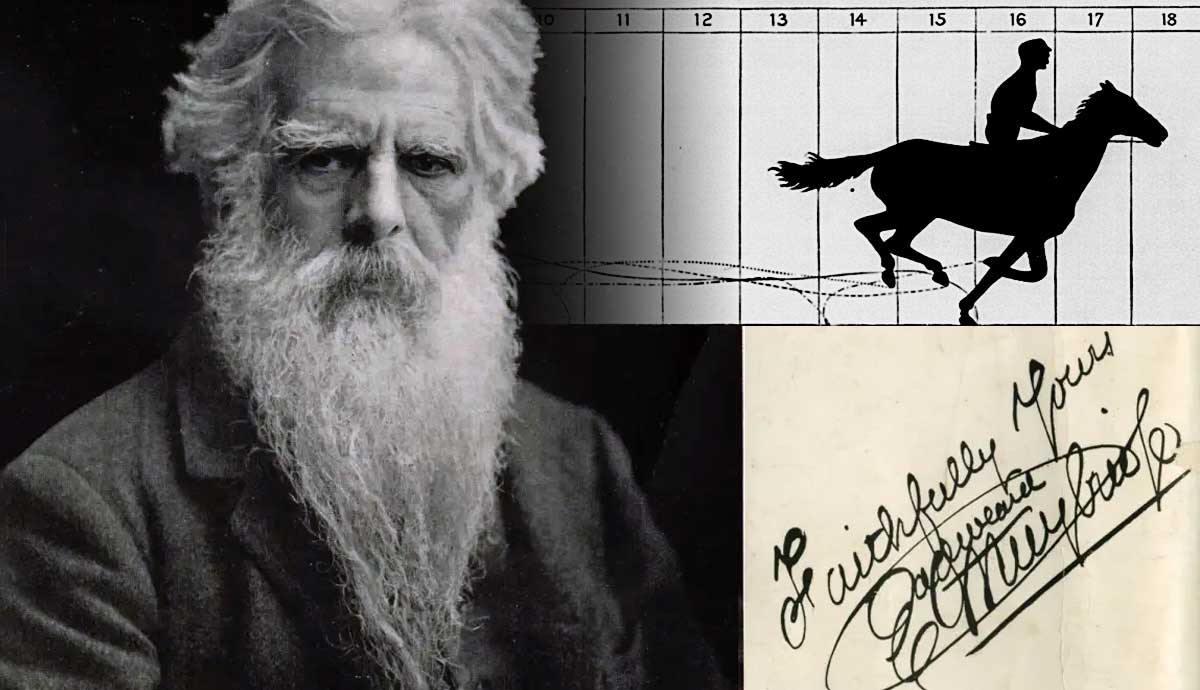

Pioneering English-American photographer Eadweard Muybridge took some of the most significant early photographs of the 19th century. Most notable in his body of work are his sequential photographs of moving people and animals, that were powerful and important precursors to motion picture cameras. Muybridge himself even eventually invented his own motion picture device, called a zoopraxiscope, for displaying his frame-by-frame documents of movement on a rotating, cylindrical disc, which could be viewed through a slit to convey to the viewer the sensation of movement.

Among his most iconic photographs are Muybridge’s step-by-step photographs of galloping horses, captured in a fascinating sequence of speed that had never been seen on camera before. But why did he choose to photograph horses in particular? We look into the key reasons why Muybridge was so obsessed with these powerful animals.

To Settle a Bet

Depicting horses in motion was common practice in art history, and in many paintings, we often see them with limbs stretched out long, clean off the ground. In the 1870s, California Governor, railroad company president, and racehorse breeder Leland Stanford was one of many who believed that a horse did indeed ‘fly’ during its fast-paced galloping speed, or what he called “unsupported transit,” which was too fast for the human eye to fully comprehend. He was so sure of his theory that he arranged a bet with a friend of $25,000 that he was correct.

Unfortunately, the limitations of photographic material meant there was no way of proving his theory. That was, until Stanford enlisted the help of Muybridge in 1872. Prior to this moment Muybridge had been taking monumental photographs of the American outback, but this particular challenge was to become his most challenging yet.

Finally in 1877, Muybridge was able to produce the series of photographs titled The Horse in Motion: ‘Sallie Gardner,’ Owned by Leland Stanford: Running at a 140 Gait over the Palo Alto Track, 19th June, 1878. At Stanford’s own private horse track in Palo Alto, Muybridge shot a series of photographs using a row of 24 lined up cameras with trip wires, each with a high shutter speed, as the horse Sallie Gardner flew past against a white backdrop.

Incredibly, Muybridge’s photographs made history, proving for the first time that a horse does lift all four feet off the ground during high motion speed. However, his photographs demonstrated that their feet leave the ground while gathered in the center, rather than being outstretched, as had been previously represented in several well-known works of art.

To Document Movement

Building on the success of his enterprise with Stanford, Muybridge developed a lifelong fascination with capturing animals in motion. He went on to take further similar documentation of horses in motion on longer tracks with a larger number of cameras, which demonstrated his technical skill in capturing finely tuned elements of movement completely invisible to the naked human eye.

While Muybridge went on to photograph a whole range of further animals and people, it is arguably for his pioneering work on horses that he is best-known. Horses in motion were a recurring feature in Muybridge’s definitive portfolio of 1887, titled Animal Locomotion: an Electro-Photographic Investigation of Connective Phases of Animal Movements.

To Create the First Moving Imagery

Muybridge’s horse studies became an important element in his experiments with the zoopraxiscope, a device now recognized as one of the first motion picture cameras. The machine operated with a series of rotating glass discs, each featuring a single photograph, which, as Muybridge proved, could be set into motion when spun around at high speed. Horses were one of his preferred subjects for demonstrating his zoopraxiscope during public lectures because of their ability to travel at such as high speed, which would no doubt have appeared particularly theatrical for his captivated audiences.