summary

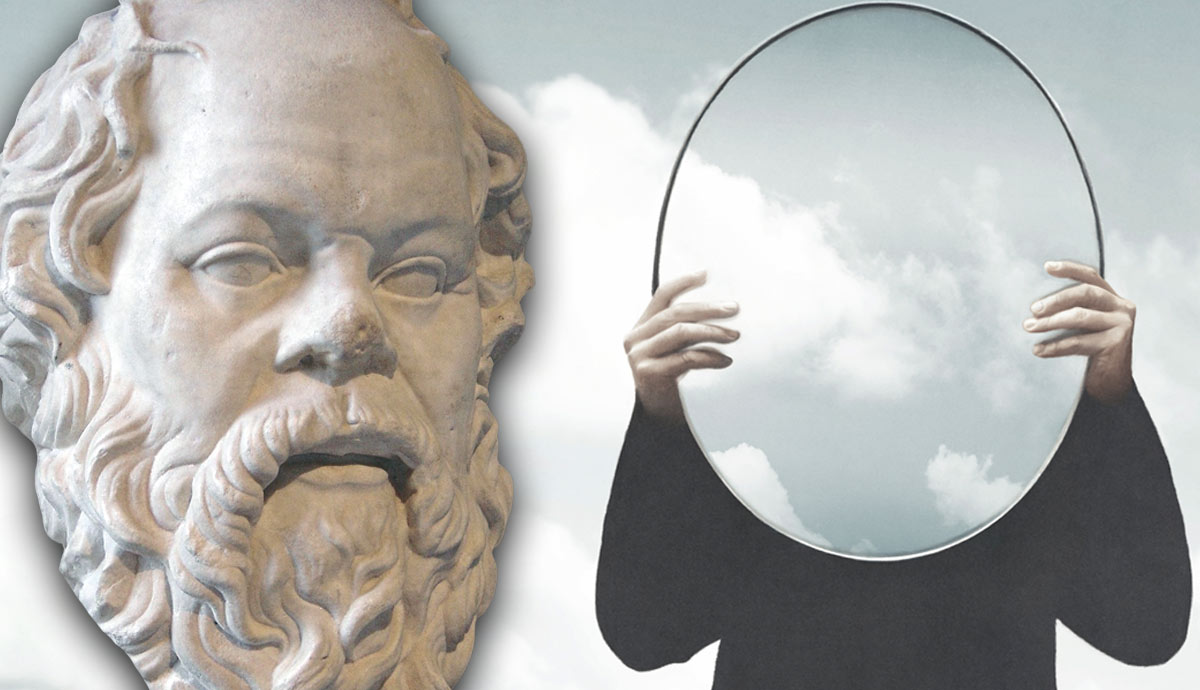

- Socratic Method: Socrates advocated for the self-examined life and encouraged constant questioning of one’s beliefs and assumptions.

- A Good Life: He advocated for a virtuous and ethical life, which included accepting the collective laws and judgment of his city, Athens.

- Death Before Dishonor: Socrates could not escape his execution, as it would place self-interest above a good life, undermining his life’s work.

- The Immortal Soul: He believed in a pre-existing immortal soul capable of recalling eternal truth through self-examination; death frees the soul from the body, which constrains true knowledge.

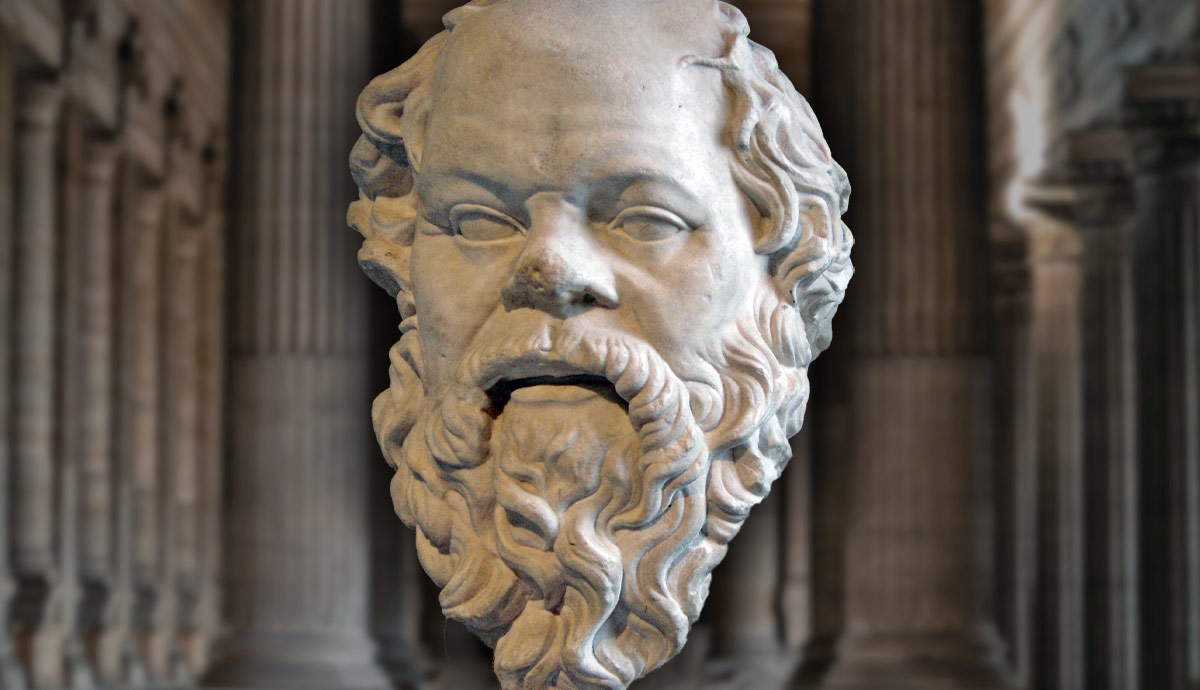

Socrates had a profound impact on the trajectory of Western philosophy despite insisting, “all I know is that I know nothing.” This claim alone could be misconstrued to suggest Socrates didn’t think there was anything that could be known, but this couldn’t be further from the truth. The existence of eternal truth is fundamental to Socrates’ philosophy. But Socrates suggested that fundamental knowledge could not be taught by teachers or the external world; these were only stimuli that helped a person recall the eternal truth held within their soul.

Living a Good Life

Socrates, who lived in 5th-century BCE Athens, left no writings of his own to reveal his philosophy. What we know about Socrates mostly comes from his student, Plato. He explains that Socrates explored philosophical ideas through conversations in which he continually pushed his companions to question the assumptions underlying their beliefs. This became known as the Socratic method, and Plato casts Socrates in fictional versions of these conversations in his “dialogues.”

According to Plato, Socrates was principally concerned with discovering what it meant to live a good life. He believed that a good life was a self-examined one, with a person constantly reflecting on their values and actions. This self-knowledge led to the virtue required for living a good life, which included self-mastery, just and ethical actions, and harmony with the soul. According to Plato, this is how Socrates lived his life, making him the “ideal philosopher.” That Socrates lived as he preached is evident in several episodes from his life.

Death Before Dishonor

Today, Socrates might be considered part of a counter-cultural movement. As a result, in 399 BCE, he was put on trial for impiety towards the Athenian gods and corrupting the youth. During his trial, Socrates chose to defend his actions in an attempt to educate the jury of his peers, rather than show regret and plead for mercy to avoid a death sentence. In Plato’s Crito, one of Socrates’ friends, Crito, sneaks into his prison cell before his execution with a plan to help Socrates flee Athens and avoid an unjust death. Socrates refuses to accept this offer unless they can both agree that fleeing would be the good and just thing to do.

As they talk, they both first agree on the importance of always acting in a good and just manner. Socrates takes this further by addressing whether the opinions of all others matter, or only the opinions of those who are good and just (or at least act as such). Crito’s main counterpoint is that the opinion of the masses, namely, Socrates’ jury, is responsible for his death sentence. Even if others are unwise, their opinions must be considered for the sake of self-preservation at least. Socrates doubles down, asserting that a good life should be valued above all other possibilities.

Socrates argues that he must accept his fate because avoiding it would mean throwing away his goal of a good life. He argues that he has lived in Athens all his life, having been nurtured and supported by the state to become who he is, and that this has always represented his acceptance of all the laws of Athens. Had he been dissatisfied, he could have left legally or tried to change any unjust laws. Now that it is too late for either, fleeing would only suggest that his good character and actions were never more important than his own self-interest. Furthermore, Socrates could not resume his way of life in any other city, since the people there would know that he fled Athenian persecution. This alone would render anything he has to say about virtue and justice insincere.

The Immortality of the Soul

Considering the Crito alone, Socrates would have needed some additional motivation for staying true to his values. If he were pursuing a good life for the sake of others’ opinions towards him, he likely wouldn’t have been sentenced to death in the first place. His motivation comes from within, and the importance of a good life depends on more than the time he has on earth. The final moments of Socrates’ life are narrated in Plato’s Phaedo, where he describes death as a separation of the body and the soul.

For Socrates, being a philosopher has meant being attracted to wisdom, ideas, and truth. Death gives the soul its chance to be freed from the body’s desires and intellectual inefficacy, meaning that it can finally grasp the knowledge and eternal truths which Socrates, like all true philosophers, has spent his life searching for.

The concept of an immortal soul comes up in many of the Platonic dialogues. The latter half of the Phaedo explores the quandary by explaining the duality of opposites, namely, the material and immaterial world. While the soul and its vessel can be analogized to other things (e.g., fire is to the body as heat is to the soul), this is not enough to conclusively prove what happens to a soul after death, or if it is truly indestructible. The Phaedo accepts the soul’s pre-existence, which is addressed in other dialogues with greater reference to individual experience.

Virtue and Knowledge as Objects of the Soul

Plato’s Phaedrus also explores the immortality of the soul as Socrates explores people’s passions and drives, and how these correspond to divine exuberances. Better yet, Plato’s Meno focuses on the nature of learning and knowledge itself to suggest an immortal soul. When Socrates and Meno discuss what all virtues have in common, their dialogue shifts from explaining how specific virtues are often conditional to how individuals must recognize their own virtue within; it isn’t enough to just be told they’re virtuous.

Socrates and Meno agree that virtue is unlike any other field of inquiry because it cannot be taught. However, even knowledge that can be taught is never imposed onto a student or pupil, but rather brought out from within them. It is that universal feeling of a concept or lesson finally clicking, which suggests both the existence of an immortal soul and a nexus of objective knowledge that the soul accesses. The Greek word for this is “anamnesis,” the idea that all learning is actually recollection; a gap being bridged between an immaterial soul and immaterial truth. Both exist before individuals live, yet their reunion is fundamental to the human condition.