Copying and plagiarism in art have probably existed for centuries, even before our ancestors fully grasped the concept of art. Getting inspired by the ideas of others is one thing, but framing works as your own could pose risks to one’s career. However, in the 20th century, many famous artists started copying older works of art. This tendency is still present in contemporary art. Many critics complain about the lack of new ideas, while others believe that copies and references are the new way to interact with art.

Copying as Training: How Contemporary Artists Learn

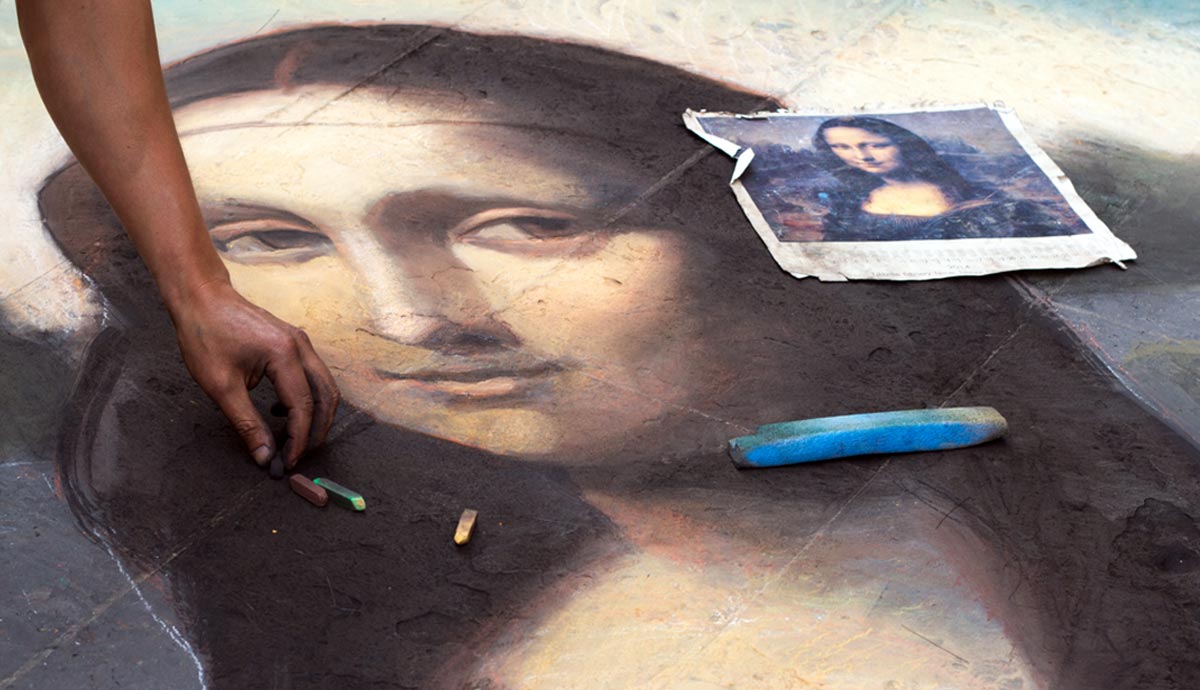

For centuries, copying remained the central element in the process of artistic education. Since the first days of the Louvre opened to the public, aspiring artists could easily access its collection, spending hours and days copying the collection’s masterpieces. Among those who trained there were artists like Edgar Degas and Pablo Picasso, who would later become involved in the Louvre heist. By copying the works of renowned artists, their younger colleagues could learn about the concepts of color, composition, and line.

Today, the practice of training artists inside museum walls still exists, although it transformed from a standard form of education into a thing of privilege. Once a year, museums like the Louvre, Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Prado accept and evaluate hundreds of artists’ applications before selecting a few who will be granted access to their collections. And even if you are lucky enough to receive the permission, you would still be subject to a long list of rules and regulations.

Museums do not allow painting exact copies of their works by insisting on changes in the scales of compositions. Artists are also forbidden to sell their copies and, in some cases, cannot even talk about their other artistic projects inside the museum walls. This rule, established by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, stopped the invited artists from promoting their work among museum visitors and attracting new customers.

However, an act of copying remains morally unambiguous only if it is committed without personal gain in mind. Legal and ethical issues arise when someone tries to present their work as the true original. Unlike in the case of forgery, the artist uses their own name to sign the work, yet relies on the concepts or ideas invented by someone else.

The art world has seen a lot of plagiarism scandals, including those related to top celebrities like Damien Hirst, who seems to collect plagiarism allegations like stamps. Yet, plagiarism has an expiration date. As decades and centuries pass, artists become ingrained into the art historical narrative, and their recognizable artworks become part of the canon. Simultaneously, they lose their immediate cultural meaning that was read by artists’ contemporaries. Artists of the younger generations, who grew up with these iconic works in sight, may find new contexts and meanings in them, making old art relatable in the new age.

Recontextualizing Old Masterpieces

Sometimes, the existing works of art become foundations for new narratives. For instance, in 1991, the famous American painter Faith Ringgold created a series of quilts titled The French Collection. Each of the nine quilts tells a fictional story of an African American woman artist from the 1920s who settles in Paris and accustoms herself to the new environment. The character, named Willia Marie Simone, meets celebrities like Henri Matisse and Josephine Baker and explores the studios of famous artists. The background of Willie Marie’s journey is formed by the tapestry of famous paintings like Mona Lisa or The Dance, recreated by Ringgold. The narrative challenges the art historical canon not by criticizing it, but by enriching it with one more character with her unique experience and worldview.

American portraitist Kehinde Wiley reinterprets the paintings by Old Masters by swapping their protagonists. Instead of affluent caucasian aristocrats, he paints Black people seated on thrones of harnessing horses. Wiley usually bases his portraits on the photographs of young men he meets on the streets of Harlem. Such an approach allows the artist to challenge the power dynamics and structures, putting people of color in positions that were historically denied to them. The artist is not fabricating history but rather constructing the sense of grandeur and power produced by Old Masters’ artworks.

Similarly, the British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare recreates iconic Western paintings in his mixed-media installations that blend sculpture and costume design. His copy of Jean-Honore Fragonard’s iconic The Swing shows a headless figure in a lavish Rococo dress. Instead of delicate rose silk and white frills, the dress is made entirely of printed cotton with ornaments closely associated with African costumes. The missing head creates a racial ambiguity: we are not entirely sure who we are dealing with. Is it an African woman who managed to get her share of European privilege, or the white colonizer appropriating the subdued land’s culture?

Urs Fischer vs Auguste Rodin: Democratization Through Appropriation

Sometimes, the use of a recognizable image can increase the sensory and emotional impression of a work of art. For most of his career, the Swiss artist Urs Fischer experimented with texture, material, and sensory perception of his works, particularly the tactile effect of a human hand against artistic material. In 2017, Fischer recreated the world-famous sculpture The Kiss by Auguste Rodin, using white plasticine instead of marble. One of the most remarkable features of Rodin’s work was its unique impression of soft skin and a living body, encapsulated in marble.

Fischer’s version of the work further emphasized the feeling of tactility. The viewers were encouraged to touch the work and reshape it, feel the material and the composition. Not only did the appropriated image contribute to the tangibility of the work, but it also dismantled the traditional hierarchies. Every visitor could become a contributor to one of the world’s greatest works of art, with their gestures equally valid as the gestures of Rodin and Fischer.

The Shaky Ground of Art Reproduction

The notorious art forger John Myatt turned his illegitimate occupation into a completely legal income source. Myatt served a short prison sentence for more than 200 forged artworks that found their way into the most prestigious art collections worldwide. After his release, he began collaborating with art crime investigators to help solve similar cases of forgery. Myatt’s main occupation is still painting copies. He calls these works “legitimate fakes” and sells copies of Monet, Van Gogh, and Cezanne for a fraction of their real prices. Despite the abundance of artists like Myatt, his notorious biography works as the perfect marketing strategy. Still, Myatt does not say that he is reinventing art but that he is offering his clients pleasant and affordable home decor.

Some famous artists may choose to copy someone else’s work with minimal intervention. In 2015, Jeff Koons, another popular target of plagiarism accusations, introduced a highly controversial project that raised the issue of the need for copies in art. Koons presented a series of crude copies of famous paintings, from Titian’s Venus to Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass, with blue spheres attached to them. The images were painted by Koon’s assistants using a paint-by-numbers technique, effectively turning famous masterpieces into coloring books. In his own eyes, Koons presented himself as a collaborator of the greatest names of art history. However, the poor execution turned the project into an uncomfortable public display of Koons’ hyperinflated ego.

Appropriation Art: Stealing as a Creative Concept of Famous Artists

The first instances of appropriation as an artistic method appeared decades before this phenomenon became widespread. Marcel Duchamp reinvented the Mona Lisa in 1919, and Manet painted his Olympia, based on Titian’s Venus of Urbino, in 1863. In the 1960s, artistic appropriation took a new turn with the rise of Pop Art, which almost entirely based itself on the reproduction of pre-invented imagery.

In the 1980s, a new art movement appeared that provoked debates on the nature of art and its limits. Appropriation art was an offshoot of Conceptualism, the movement that valued an artistic idea more than its execution. Appropriation art took the concept of borrowing to the extreme, with artists grounding their entire oeuvres in repetition.

Richard Pettibone created miniature copies of great artworks by artists like Constantin Brancusi and Andy Warhol. Upon accusations of creative impotence, Pettibone explained that his idea came to him through his childhood hobby of model trains. The tiny mechanisms had entire worlds built and reconstructed around them, and Pettibone decided to enrich these worlds with works of art. On the other hand, artist Sherrie Levine claims that her appropriation of the works by famous male artists is a gesture of feminist justice. Her most famous appropriated works are images of famous photographs made by other artists, rephotographed from exhibition catalogs and passed as her own.