Hanna Wilke explored feminist ideas through several mediums such as sculpture, performance, video, and photography. Objects looking like vulvas became her signature artwork. She used her body in performances, videos, and photos which were criticized by some feminists. Wilke died of lymphoma when she was only in her early fifties. She documented her final years, the illness, and its treatment through photos, videos, and other mediums.

Hannah Wilke’s Early Life and Education

Hannah Wilke was born Arlene Hannah Butter in New York in 1940. When she was in her mid-twenties, she stopped using the name Arlene. The surname Wilke came from her future husband Barry Wilke. She grew up in a Jewish family in the 1940s which once led her to say that she would have been branded and buried if she wasn’t born in the USA. Her mother’s parents came from Hungary and her father’s parents were Russian-Polish. Wilke’s extended family spoke both Yiddish and English.

From 1956 to 1961, she attended the Tyler School of Art at Temple University in Philadelphia. Wilke graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts and a teaching degree. Wilke is mainly known for her work as an artist, but she also worked as a teacher for roughly 30 years. She moved back to New York in 1965 where she would stay until her death in 1993. After her graduation, she worked as an art teacher at a high school in Plymouth Meeting in Pennsylvania, and in White Plains in New York. She also taught sculpture at the School of Visual Arts in New York.

Hannah Wilke’s Sculptures

Hannah Wilke became known for her vulva-like sculptures. These sculptures made Wilke one of the first artists who used the imagery of female genitalia to address feminist issues. She started to make them early on in her career and created them out of different materials such as terracotta, latex, ceramic, and chewing gum. Wilke once said that for her the idea of vaginal imagery was primarily about inner feeling and the feeling of getting beyond oneself that one experiences when making love. One example of her vulva-like work is titled Ponder-r-rosa 4, White Plains, Yellow Rocks from the year 1975. It consists of 16 pieces reminiscent of female genitalia made out of latex, mounted on a wall.

Performances, Videos, and Photographs

In the 1970s, Hannah Wilke started doing performances. Her body was an essential element of these performances which were documented through photos and videos. She called them performalist self-portraits. In these works, Wilke challenged stereotypical depictions of women by recreating them in an ironic and critical way.

Her work titled Gestures from 1974 consists of a black-and-white video that lasts about half an hour. During the video, Wilke performs various gestures and expressions by only using her hands and face. She pulls at her skin, kneads it, strokes it, and massages it. While some of the motions seem pleasant, others look more violent. The video also shows Wilke in poses that are similar to the depictions of women in advertisements, therefore emphasizing the performative aspects of femininity.

In another video work called Through the Large Glass, the artist is performing a striptease in front of Marcel Duchamp’s piece titled The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (1915–1923) at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The viewer can see Wilke’s performance through the cracked glass of Duchamp’s work, which is also called The Large Glass. The cracks were the result of an accident, but Duchamp decided to leave them in the work.

In reference to the title of Duchamp’s work, Wilke, who at the beginning of the video is wearing a white suit and a fedora, is stripping bare. Wilke once said that in order to honor Duchamp one has to oppose him. Her poses are similar to those seen in fashion photography of the 1970s. Wilke, therefore, engages with typical images of modern femininity such as the stripper or the fashion model.

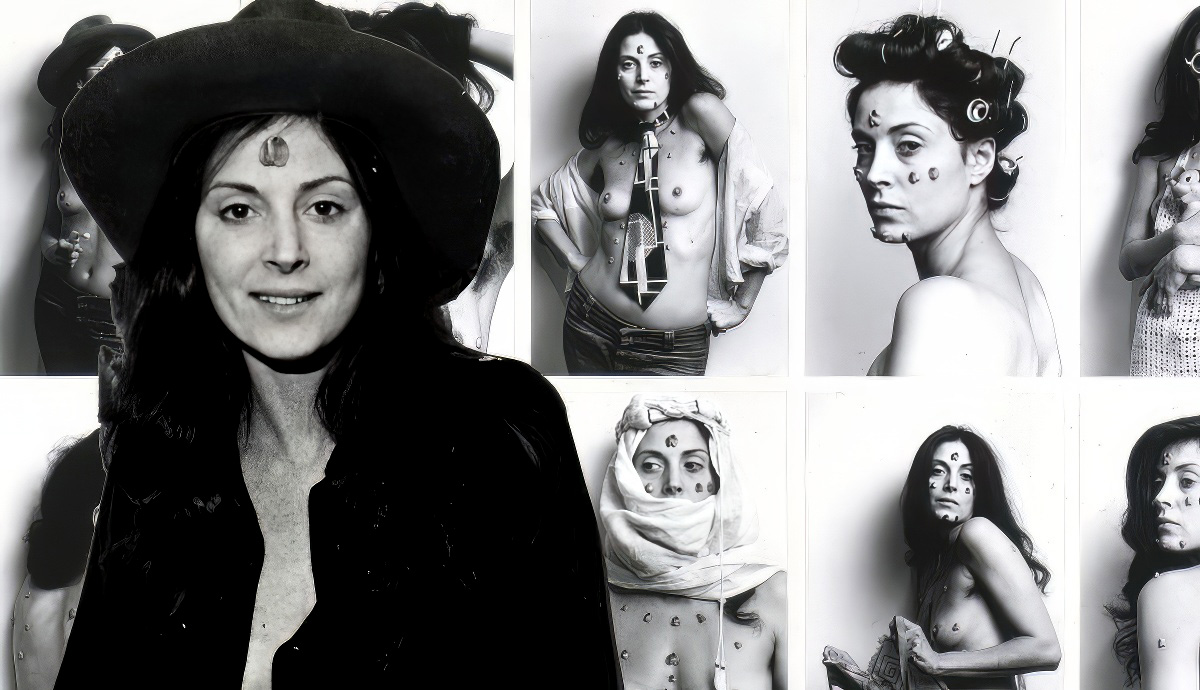

Another important work that combines performance and photography is called S.O.S. – Starification Object Series from 1974 to 1982. During the first performance, pieces of colored gum were handed out to the members of the audience who were asked to chew the gum and then give it back to the artist. The topless Wilke would stretch the chewed gum and mold it into tiny sculptures that she would place on her skin. Wilke said that she decided to use chewing gum because it served as an ideal metaphor for the American woman: Chew her up, get what you want out of her, throw her out and pop in a new piece. The pieces of gum in the shape of vulvas have been interpreted as scars with which Wilke disrupts the gaze of the viewer and the objectification of the female body.

As the title suggests, the scar-like pieces of gum are necessary to make Wilke a star but they also show the wounds she had to endure to become one. In a series of photos, Wilke displayed her body in different poses covered with pieces of gum. Wilke posed in ways that evoke images seen in fashion magazines and advertisements. She also used props like sunglasses, toy guns, and cowboy hats.

Feminism and Controversy

Hannah Wilke’s art focuses on feminist issues, but she also received criticism from some feminists. Wilke’s own attractiveness, which is very much visible in her work, was seen as problematic. The well-known art critic, activist, and feminist Lucy Lippard described Wilke as a glamor girl who confused her roles as a flirt and feminist and a beautiful woman and artist. Lippard accused Wilke of flaunting her body in a supposedly parodic way even though Wilke plays the role of a glamorous and attractive woman in real life. According to Lippard, this led to politically ambiguous manifestations.

Hannah Wilke reacted to this criticism by making a work called Marxism and Art: Beware of Fascist Feminism. She used a photo of her S.O.S. Starification Object Series in which she exposed her upper body covered with a necktie and her famous vulva-like pieces of gum. The poster deals with the harmful effects of a branch of feminism that criticize women for the way they look and act.

Hannah Wilke’s Final Years

Hannah Wilke was diagnosed with cancer in 1987. She struggled with the illness until she died of lymphoma on January 28, 1993, in Houston, Texas. She documented the effects cancer and chemotherapy had on her body in her last series titled Intra-Venus. Her husband Donald Goddard took the photos of Wilke for the series.

While the artist had been accused of flaunting her attractiveness in her earlier works, she defied this notion in her Intra-Venus series which is a testament to the deterioration of the body caused by illness and chemotherapy. Wilke once responded to criticism by saying: People often give me this bullshit of, ‘What would you have done if you weren’t so gorgeous?’ What difference does it make? . . . Gorgeous people die as do the stereotypical ‘ugly.’ Everybody dies.

The honest photos of the Intra-Venus series, an obvious wordplay on intravenous treatment, often show Wilke in an exhausted condition, losing her hair or being bald, with a swollen body, receiving treatment in the hospital, sitting on the toilet, or lying in bed. One of the images, though, shows Wilke laughing and in a seemingly good mood. The final years of her life were also documented through the Intra-Venus Tapes, which were shot by Wilke herself, her husband Donald Goddard, and other people. They also document her life and the effects of her illness.

In another series relating to her illness called Brushstrokes, Wilke attached pieces of her hair that fell out during chemotherapy to paper. The title refers to how the hair was caught in her brushes while it was falling out. Many of the photos from the Intra-Venus series are reminiscent of images from art history. The picture of Wilke covering her head with a blue blanket from the hospital in Intra-Venus Series No. 4, for example, is similar to many Madonna depictions. One image showing Wilke in a bathtub with open legs was compared to Courbet’s The Origin of the World by Nancy Princenthal in her book Hannah Wilke. The strong facial expressions seen in Intra-Venus Series No. 5 were apparently inspired by the character studies of German-Austrian sculptor Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, who lived in the 18th century.

During her lifetime, Hannah Wilke’s work was exhibited internationally and in the USA. She received grants from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts. From 1972 on, the Ronald Feldman Gallery in New York featured her art in several exhibitions.

Despite the controversies surrounding the use of her own body in her work, Wilke is considered an important feminist artist. Wilke’s work was part of the traveling exhibition WACK!: Art and the Feminist Revolution, which made it to the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington D.C., the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, and the Vancouver Art Gallery in Canada. Her work was also part of the exhibition Shifting the Gaze: Painting and Feminism at the Jewish Museum in New York.