Italy has a unique distinction in both World Wars: it switched sides! In 1914, when World War I began in Europe, Italy was a Central Power allied with Germany and Austria-Hungary. The following year, however, Italy entered the war as an Allied Power, fighting against Austria. Almost thirty years later, Italy was in a similar situation. Once again, Italy was an ally of Germany and Austria (which had been annexed by Germany prior). In October 1943, one month after the Allies landed in Italy relatively unopposed due to secret negotiations, the country switched sides again to join the Allies. Why did Italy make both of these switches and did it work out in Italy’s favor?

Setting the Stage: The Nation of Italy Emerges

Unlike most Western European nations, Italy and Germany were composed of separate and independent states until the latter half of the 1800s. Italy unified in 1871 after the Franco-Prussian War, which also saw the unification of Germany. These two nations vied for power and prestige among the other developed nations of Western Europe, including at the Berlin Conference in 1885. Due to their junior status, neither Italy nor Germany received much colonial territory in the Scramble for Africa, which precipitated the conference.

Economic development in the new nation of Italy was relatively slow during the 1880s and early 1890s. Italy’s economic weakness was one push factor in convincing hundreds of thousands of Italians to emigrate to the United States. During the 1890s, there were so many remittances of money sent from the US back to Italy that it had a noticeable economic effect. By the early 1900s, however, Italy’s economy had stabilized thanks to its new central bank. The recent economic growth likely contributed to Italy’s decisions regarding World War I.

Setting the Stage: Pre-World War I Alliances

Western Europe had not undergone a major war since the era of Napoleon, and by the late 1800s many powers were itching to use a show of force to cement their status. Likely emboldening their posturing was a system of alliances that had been created, requiring all members to respond militarily to an attack on anyone. The Triple Entente alliance consisted of Britain, France, and Russia, threatening to strike the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy from both the west and east.

Italy joined an existing alliance between Germany and Austria-Hungary in 1882, expanding it into the Triple Alliance. Although Italy was geographically convenient as an ally and could provide additional manpower in the event of a conflict, German leader Otto von Bismarck worried that Italy’s vast coastlines left it wide open for attack. Many also viewed Italy’s government as too liberal and ill-suited for wartime rigors. Italy’s primary concern was a potential attack by France, with which it shared a small segment of border.

1914: World War I Begins, but Italy Remains Neutral

On June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary was assassinated in Sarajevo, Bosnia. This began a chain of events that swiftly pulled almost all the powers in Europe into war…except Italy. Despite being a member of the Triple Alliance, Italy chose to remain neutral in the growing conflict. Because Germany went on the offensive against France quickly, as part of its Schlieffen Plan, Italy was not obligated to defend it or Austria-Hungary against an aggressor.

Italy’s decision to remain neutral likely stemmed from multiple factors, such as economic weakness compared to its allies, a geographically unsuitable position for offensives against the Triple Entente, and weak socio-cultural ties to its allies. The quick bogging down of the Western Front in France into horrific trench warfare also certainly dissuaded many Italians from joining the conflict. Political feuds over territorial expansion in the Balkans and the transfer of Italian-speaking provinces between Italy and Austria-Hungary also delayed Italy’s entry.

1915: Italy Joins World War I as an Allied Power

Despite the ongoing war, Austria-Hungary refused to compromise with Italy, leading to Italy’s decision to switch sides and join the Triple Entente. On April 26, 1915, a secret deal was signed between Britain, France, and Italy, allowing Italy to seize the Italian-speaking contested provinces from Austria-Hungary. A week later, Italy publicly left the Triple Alliance. On May 23, Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary, completing its switching sides.

At first, Italy was relatively unprepared for war, with a standing army of just 300,000 men. Although it quickly engaged in full mobilization, it soon became mired in a stalemate similar to France. The Italian Front was fought mostly between Italy and Austria-Hungary along the Isonzo River in mountainous terrain. Unfortunately for Italy, the Austro-Hungarians usually held defensive positions on the high ground, and Italy struggled in the war. In 1917 and 1918, Austria-Hungary and Germany went on the offensive in Italy, hoping to draw British troops away from France. However, by October 1918, German and Austro-Hungarian forces in Italy were exhausted, and they ended up having won no territory.

Post-WWI: Did Italy’s Switch Work in Its Favor?

World War I was very costly for Italy, especially with some 460,000 men killed. As the fifth Allied Power, which included the Triple Entente, the United States, and Italy, Italy spent some $12.4 billion on the conflict. This resulted in a large public debt that peaked at 180 percent of GDP, mostly owed to Britain and the United States. Although Italy tried to negotiate with its two largest creditors, it was unable to secure a reduction in its debt. The economic situation contributed to a two-year period of political crisis known as Biennio Rosso, or “two red years.”

The diplomatic aftermath of World War I, formalized by the Treaty of Versailles, left Italy without desired territorial gains. Although Italy’s secret treaty in London in 1915 gave it territories from Austria-Hungary, the Treaty of Versailles did not agree. However, the Italian delegates at the Paris Peace Conference, although accepting that they would not receive the territories promised in 1915, refused to give up the receipt of the small town of Fiume in the Balkans. Eventually, Italy had to accept a less-than-desired post-war settlement, sometimes known as Vittoria Mutilata, or “mutilated victory.”

1936: Mussolini’s Italy Allies With Hitler’s Germany

The Vittoria Mutilata and wounded Italian pride, similar to the humiliation of Germany after World War I, led to easier public acceptance of fascism in the two decades that followed. In 1922, following the Biennio Rosso, Benito Mussolini’s new fascist party was swept into power by Italians desiring a strong, law-and-order government. However, despite Mussolini’s rapid rise to power, he did not actually possess the ultimate authority of a true dictator—there was still the king, Victor Emmanuel III. The king agreed to Mussolini’s rule, as the fascists had pledged to uphold the king.

A decade later, the Nazi Party rose to prominence in Germany, and Adolf Hitler was appointed as chancellor. In June 1934, Hitler and Mussolini met for the first time, shortly before Hitler promoted himself to Führer of Germany. On November 1, 1936, Mussolini announced the “Rome-Berlin Axis” in a speech given in Milan, Italy. The two growing powers were drawn together by both being disdained by the international community—Germany for rejection of the Treaty of Versailles and Italy for its war of aggression in Africa.

November 1942 – July 1943: Axis Begins Losing

When World War II erupted in Europe on September 1, 1939, Italy again remained neutral. Despite being a strong ideological supporter of Hitler, Mussolini did not feel his country was well-prepared for war. However, on the eve of France’s fall to the Nazis, Italy decided to join the war on June 10, 1940, declaring war on both France and Britain. For the next year, Italy benefited tremendously from its alliance with Germany—the more powerful ally saved it from defeat in both Greece and North Africa in 1941.

After Operation Barbarossa and the opening of the Eastern Front, however, Italy’s wartime fortunes began to wane. Italian forces struggled on the Eastern Front, and its North Africa fortunes were struck by twin blows in the autumn of 1942: the mass arrival of US troops as part of Operation Torch and the British victory in the Second Battle of El Alamein. Between November 1942 and May 1943, Italian and German forces in North Africa were steadily squeezed out through Tunisia. On May 13, 1943, the remaining Axis troops in North Africa surrendered…now Italy itself was a target.

July – September 1943: Secret Negotiations With Allies

With the North Africa front eliminated, the Axis Powers waited to see where the Western Allies (Britain, Canada, and the United States) would strike next. Unfortunately for Mussolini, the planning had already been done, and Sicily was invaded in July 1943 in Operation Husky. Equally unfortunate for Mussolini was the fact that his defeat in North Africa had already launched plots against his rule. On July 25, after Sicily was lost to the Allies, Mussolini was deposed by King Victor Emmanuel III and arrested. He was replaced as prime minister by Marshal Pietro Badoglio.

Badoglio initially pledged to continue the war as Germany’s ally but was secretly negotiating with the Western Allies. He did not want his country decimated by a violent invasion, but he also did not want to upset the Germans, who were spread throughout Italy as wartime allies. The negotiations resulted in the Armistice of Cassibile, which would allow Allied troops to land on the Italian mainland. However, the Germans had been expecting such a plan and quickly seized control of most of Italy as part of Operation Achse.

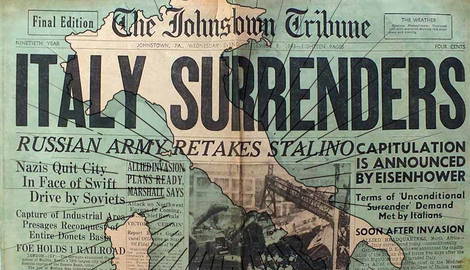

October 1943: New Italian Government Joins Allies

Mussolini was rescued by German commandos and installed as the leader of the Italian Social Republic, a Nazi-controlled state. German troops in Italy committed many atrocities, including rounding up Jewish people as part of the Holocaust. As the Allies began gaining ground in Italy, pushing northward, the Badoglio government, which controlled southern Italy, declared war on Germany on October 13, 1943. Now free, Italy was a member of the Allied Powers.

However, because Italy was effectively divided between free Italy in the south and the Nazi-controlled Italian Social Republic (ISI) in the north, a civil war was at hand. Although the militaries of the United States and Britain did most of the heavy fighting against the ISI and its German allies, anti-fascist partisans from Italy also assisted. These partisans continued to fight German occupiers and Mussolini’s forces until the end of the war and even caught and executed Mussolini himself at the end of April 1945.

Post-WWII: Did Italy’s Switch Work in Its Favor?

As Nazi Germany faced complete destruction by May 1945, with the Western Allies having entered it from the West and the Soviet Red Army having entered it from the East, it is undeniable that Italy made a shrewd choice in switching sides. Having remained a dedicated German ally would have resulted in a violent invasion by the Western Allies, resulting in more death and destruction than Italy endured. Badoglio’s decision to both surrender to the Allies and then declare war against Germany helped preserve some Italian infrastructure and political autonomy.

However, Italy still struggles with its fascist past, as it did not have to endure a post-war de-Nazification process like Germany did. Italy’s mediocre military performance did not win it much respect from the Allies, nor was its surrender and declaration of war against Germany viewed as noble—Italy was seeking self-preservation. Despite some mockery of the Italian military at the time, the relative lack of Italian aggression may be one reason its international military deployments, second only to Britain among European powers, are more accepted today. Both former Axis Powers in Europe are currently members of NATO, firmly allied with the United States, Canada, and Britain.