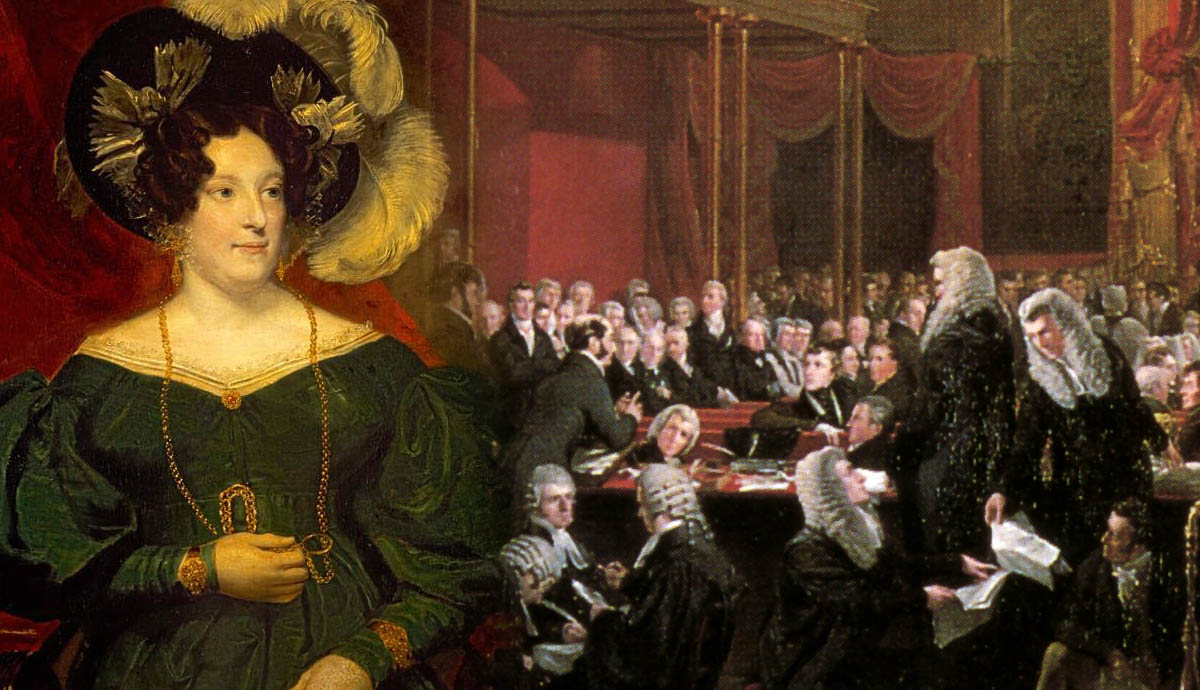

The marriage of Queen Caroline of Brunswick to King George IV of the United Kingdom was destined to fail. The future king couldn’t stand the sight of his wife when he met her for the first time just three days before their wedding. They separated a year after their wedding, and Caroline was eventually exiled from Britain for six years during which their only child died. When Caroline did return to British shores as Queen, she was not allowed to attend her husband’s coronation. Caroline died less than three weeks later, but her cause had gained support among proponents of women’s rights and political reform.

Queen Caroline Is Absent From King George IV’s Coronation Day

On July 19, 1821, King George IV’s coronation was held at Westminster Abbey. George IV had already been King since his father’s death 18 months earlier, and due to his father’s poor mental health, he had been acting as King in the capacity of Prince Regent since 1811. George IV’s coronation was the most expensive and extravagant coronation in British history. The ceremony began in Westminster Hall and was followed by a procession to Westminster Abbey that was viewed by the public.

The King’s herbwoman, along with her six attendants, scattered flowers and sweet-smelling herbs along the path to ward off plague and pestilence. They were followed by Officers of State, three bishops who accompanied the king, Barons of the Cinque Ports, and the peers of the realm and other dignitaries. One person was conspicuously absent: George IV’s wife Queen Caroline.

This was not from want of trying by Caroline. At 6 a.m., her carriage arrived at Westminster Hall. She was greeted with applause from a sympathetic section of the crowd although “anxious agitation” was felt by the soldiers and officials supervising the door. When the commander of the guard asked Caroline for her ticket, she replied that as Queen she didn’t need one. Nevertheless, she was turned away. Queen Caroline and her chamberlain, Lord Hood, tried to get in through a side door and through the nearby House of Lords (which was connected to Westminster Hall), but these attempts were foiled too.

Caroline and her entourage returned to her carriage, and 20 minutes later they arrived at Westminster Abbey. Lord Hood approached the doorkeeper who was probably one of the twenty professional boxers who had been hired for the event.

“I present to you your Queen,” said Lord Hood, “do you refuse her admission?”

The doorkeeper stated that he couldn’t let anyone in without a ticket. Lord Hood had a ticket, but the doorkeeper told him that only one person could be admitted with that ticket. Caroline refused to take Lord Hood’s ticket and enter alone.

Queen Caroline shouted, “The Queen! Open!” and the pages opened the door. “I am the Queen of England!” she remonstrated, to which an official roared at the pages, “Do your duty… shut the door!”

The door to Westminster Abbey was slammed in Caroline’s face. The Queen’s party was forced to retreat. The nearby crowds who witnessed this shouted, “Shame! Shame!”

Who Was Caroline of Brunswick?

Queen Caroline was born Princess Caroline of Brunswick (in modern day Germany) on May 17, 1768. Her father was the Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, and her mother was Princess Augusta of Great Britain, King George III’s older sister. (This made Caroline and her husband first cousins.) Caroline became engaged to the future King George IV in 1794 although they had never met. The alliance came about because the profligate King George had amassed debts of some £630,000, an enormous sum at the time, and the British Parliament only agreed to pay off these debts if the heir to the throne married and produced an heir. When George and Caroline finally met, days before their wedding on April 8, 1795, George was said to be disgusted by her looks, body odor, and lack of refinement. The dislike was mutual.

Prince George was already “married.” He married Maria Fitzherbert in 1785, but because his father had not consented to it, the marriage was invalid under English civil law. Mrs. Fitzherbert, as she was known, was Roman Catholic, so if the marriage had been approved and valid, George would have lost his place in the British line of succession due to laws that prevented Catholics or their spouses from becoming monarch. However, Pope Pius VII did declare the marriage to be sacramentally valid. This relationship ended in 1794 on George’s engagement to Caroline.

George humiliated his wife by sending his mistress, Lady Jersey, to be her lady-in-waiting. It was said of the marriage that “the morning that dawned on the consummation witnessed its virtual dissolution.” George and Caroline’s only child, Princess Charlotte, was born one day short of nine months after the wedding. The couple separated soon after Charlotte’s birth. On April 30, 1796, George wrote a letter to Caroline to agree the terms of their separation.

“Our inclinations are not in our power; nor should either of us be held answerable for the other, because nature has not made us suitable to each other.”

George even assured Caroline that if Princess Charlotte were to die, Caroline would not have to engage in “a connection of a more particular nature” to conceive another legitimate heir to the throne. He finished by writing, “As we have completely explained ourselves to each other, the rest of our lives will be passed in uninterrupted tranquility.” The marriage was over.

The Princess’s Life After Her Separation

By the turn of the 19th century, Caroline was living in a private residence near Greenwich Park, London. While there, rumors began to circulate about her immodest and immoral behavior. There were allegations that Caroline had birthed an illegitimate child, behaved lewdly and inappropriately, and sent letters with obscene drawings to a neighbor. In 1806, with the encouragement of his brothers, Prince George laid charges against Charlotte in what came to be known as the “Delicate Investigation.” It was proven that Caroline was not the mother of the young boy in question, but the investigation harmed her reputation.

Despite this investigation against her, Caroline remained a more popular figure than her widely disliked husband. When George became Prince Regent in 1811, his extravagance made him unpopular with the public. George also restricted Caroline’s access to her daughter and made it known that any friend of hers would be unwelcome at the Regency Court.

By 1814, an unhappy Caroline reached an agreement with the Foreign Secretary, Lord Castlereagh. She agreed to leave the UK in exchange for an annual allowance of £35,000 as long as she didn’t return. Both Caroline’s daughter and an ally in the Whig opposition political party were dismayed at her departure because it meant that Caroline’s absence would strengthen George’s power and weaken theirs. Caroline left the UK on August 8, 1814.

Caroline on the Continent

Caroline remained away from Britain for six years. She traveled widely, and early on in her travels she hired an Italian courier named Bartolomeo Pergami whom she had met in Milan. He was soon promoted to major domo, and later Caroline moved in with him and his whole family into a villa on Lake Como. Rumors got back to the UK; the poet Lord Byron and her lawyer’s brother were certain that the pair were lovers.

Tragically, Princess Charlotte died in childbirth in November 1817; her son was also stillborn. Caroline no longer had hopes of regaining her status in Britain upon her daughter’s ascension to the throne. By 1818, George wanted a divorce, but this was only possible if adultery by Caroline could be proven. The British Prime Minister Lord Liverpool sent investigators to Milan in September 1818.

The “Milan Commission” sought potential witnesses who would testify against Caroline. However, the British government was keen to prevent a mass scandal and preferred to negotiate a long-term separation agreement between the estranged royal couple rather than grant a divorce. Before this could occur, King George III died on January 29, 1820. Caroline was now Queen Caroline of the United Kingdom and Hanover.

The British government was now willing to offer Caroline £50,000 to stay out of the country, but this time she refused. Negotiations to keep her away had stalled over the issue of the liturgy. While King George IV was inclined to introduce Caroline to European royal courts, he refused to allow her name to be included in prayers for the British royal family in the Anglican Church. At this insult, Queen Caroline decided to return home and the King decided to make good his threat of a divorce.

The Queen Returns to the UK

Caroline returned to the UK on June 5, 1820. Large crowds cheered her as she made her way from Dover to London. George IV and his government were increasingly unpopular after the Peterloo Massacre and the oppressive clampdown of the Six Acts. It was noted that the middle and working classes appeared to be particularly supportive of Caroline; she became a popular figure for anti-government and anti-monarch protesters to rally behind.

The day after Caroline returned to the UK, the “Bill of Pain and Penalties for an Act to deprive Caroline of the rights and title Queen Consort and to dissolve her marriage to George” received its first reading in the House of Lords. The second reading took the form of a trial, with witnesses called and cross-examined. The Bill passed its second reading by 119 to 94 on November 6, marking the end of the trial. By the third reading, the majority in favor was reduced to just nine votes. Lord Liverpool decided not to pursue the Bill further because he knew it stood little chance of passing in the House of Commons. The Prime Minister announced that “he could not be ignorant of the state of public feeling with regard to this measure.”

Queen Caroline’s Final Months

When she appeared at the House of Lords during her “trial,” Caroline’s coach was escorted by a cheering mob. There were also huge celebrations when the divorce bill was dropped in November. However, after a series of defeats for the Whigs in the House of Commons in January and February of 1821, they gave up her cause. By the time she tried to gain access to her husband’s coronation, although many cheered there were also those who hissed at her.

Queen Caroline died a mere 19 days after her husband’s coronation. Riots broke out at her funeral procession. She specified in her will that her coffin plate should read “To the memory Caroline, of Brunswick, the injured Queen of Britain” but this was denied. In particular, the events of the last year or so of her life sparked questions in British society about the rightful role of Parliament, the monarchy, and the people.

Much of what had occurred to Caroline in 1820 “highlighted the inequalities suffered by women and captured the spirit of radicalism that had been afloat in Britain since 1815.” People, especially women, questioned the divorce laws that favored men in the crime of adultery. Radicals sought political reform. Queen Caroline had become a rallying point for both these causes.