In the Aztec mythos, Huitzilopotchli sought revenge on his sister Coyolxauhqui for attacking their mother, throwing her head into the sky to become the moon watching over. In the Maya mythos, Buluc-Chabta wore a necklace made of human eyes. Brutality and war were often the way of life across ancient Mesoamerica, and as they sought to explain the chaotic world around them, they naturally became an integral part of their mythology.

1. Ancient Americas: Death Is a Way of Life

While not every Mesoamerican myth or legend includes a brutal attack or sacrifice to the gods, the groups living in Mexico, Central, and South America before the Spanish conquests in the 16th century regularly encountered life-threatening situations. Many of these groups passed down or incorporated their beliefs through both cultural and wartime connections with each other. Originating with the Olmec and passed down to the Maya and Aztec, each of these civilizations shared similar beliefs and practices.

Daily life was treacherous in Ancient Mesoamerica—just tending to the next maize harvest could be deadly. The wildlife alone was a constant danger. From jaguars to snakes, crocodiles to dart frogs, and all the poisonous insects, these powerful and deadly creatures and critters fascinated the local groups. Storms and droughts were also notoriously brutal, wiping out entire crops and creating famines. It is no surprise that many Mesoamerican deities reflected the natural threats around them.

Nature was not the only danger. Other tribes could be watching and waiting just as intently as the jaguars. Warring with neighboring people and incoming tribes was a fact of life in Ancient Mesoamerica. As different groups spread across the land, whether expanding their empires or relocating, they encountered other groups with similar intentions.

It was believed that in trying times, whether it be disease, famine, or other threats, sacrifice was required to satisfy whichever god was unhappy. Human blood was so vital to life that it was seen as a perfect offering. Meanwhile, prisoners of war were often kept alive for human sacrifice, either to thank the god they led them to victory or as a way of taking the precious lifeblood of the enemy. Often, these human sacrifices went willingly.

2. Early Religion: the Olmec Mythos

Famous for the Colossal Heads, the Olmec civilization, which existed from approximately 1200 BCE to 400 BCE, is known as the first prominent group of people living in Central Mesoamerica. Widely considered to be the first Mesoamerican civilization, the Olmec people are the earliest known culture to live in present-day Mexico. Much of what they established during their extensive reign would later be incorporated into the other groups that emerged later in Central Mesoamerica.

Unfortunately, much of the Olmec religion is lost to time. What archaeologists have discovered about their religious practices suggests a belief system similar to their successors, the Maya and Aztecs. Archaeologists have found early versions of Maya and Aztec gods in Olmec inscriptions and cave paintings, leading many to believe the Olmecs originated much of the brutal mythos in Ancient Mesoamerica. The few known deities worshipped by the Olmecs share characteristics with other gods seen in later mythology, including the Feathered Serpent god known to the Maya as Kukulcan and the Aztecs as Quetzalcoatl.

Evidence shows that their religious practices included bloodletting (causing intentional harm to release blood) and body piercings through the use of stingray spines, obsidian blades, and other sharpened artifacts. These blades, seen in later groups, are a significant connection between the elusive Olmec religion and future Mesoamerican practices.

3. Explaining the Natural World: Mayan Mythology

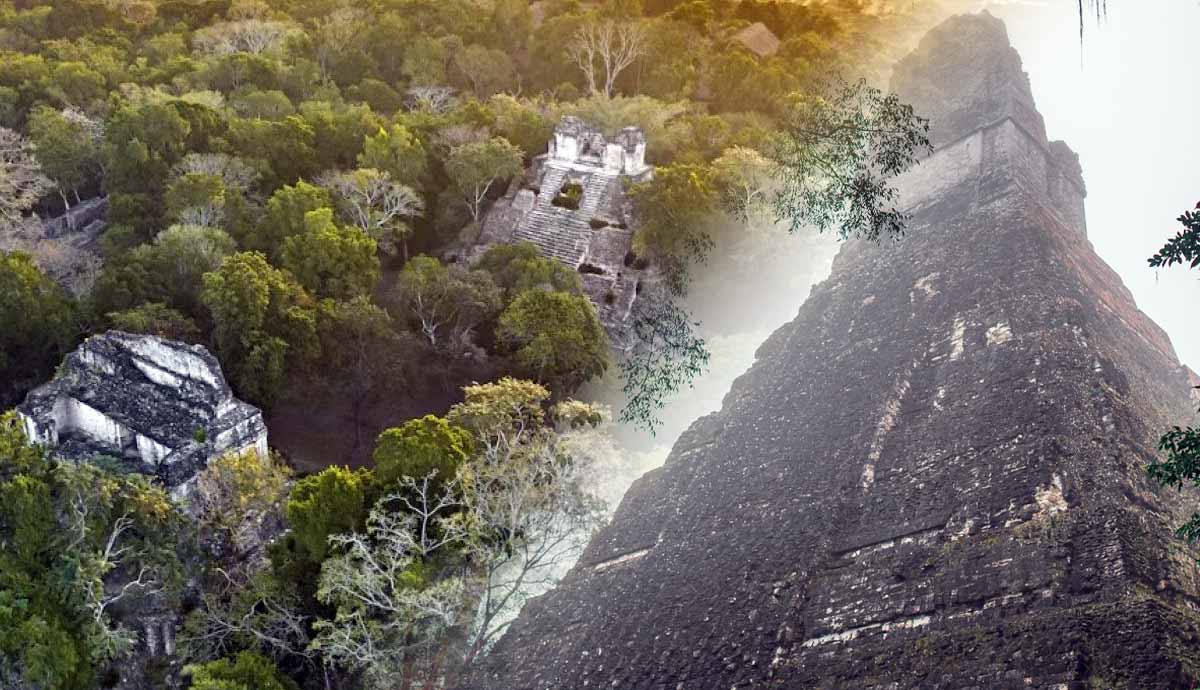

A common feature of Mesoamerican societies was their deep connection to nature, and the Maya, who lived from 250 CE to 950 CE, are a prime example. Located in what are now Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, and Southern Mexico, the Maya were a thriving civilization whose descendants still live in Central America today.

Maya mythos revolved around what they saw in the natural world. Though the exact details vary between individual stories, the Maya believed their people were created through maize, or corn, as outlined in the creation story Popol Vuh. According to the Popol Vuh, the creation of the world included gods of death, disease, and jaguars, all very real and dangerous threats to the ancient people. Given the natural perils surrounding them, the Maya mythos and religious practices reflected that threat.

The Maya pantheon of gods consisted of more than 250 deities. These deities varied in popularity across different villages and towns, but the primary gods remained consistent across the empire. Hunahpu and Xbalanque, known as the Hero Twins, are the main protagonists of these myths. The Hero Twins fought off the forces of darkness and revived their father’s body, bringing him back from the land of the dead.

Xibalba, also called Mitnal, the Maya realm of the dead, was home to the more brutal deities such as Camazotz, who resembles a bat and drinks blood, and Cizin, a death god with a necklace made from human eyes who punishes evil-doers in the afterlife. The deity of war, known as Buluc-Chabtan, is the main god to whom prisoners of war and other citizens were sacrificed. Sacrificial victims were given a harsh honor but were often depicted receiving blessings in the afterlife.

Even in ancient times, people understood the importance of blood to the human body. Blood was considered the life force of a person, imbued with their essence or power. In religious practices, it was very common to endure self-inflicted piercings of the tongue or genitalia in honor of the gods, using sharpened obsidian blades or stingray spines like the Olmec. While not every Maya deity was worshipped in this way, many of the gods within the Maya mythos desired such physical sacrifices. The mythos not only reflected the ways of war and life for the Maya, but emphasized their precarious existence through religious practices.

4. Confronting the West: Aztec Mythos

The Aztec civilization, from 1345 CE to 1521 CE, thrived in central Mexico until the eventual conquest by European colonists who viewed the indigenous religious practices as barbaric and in need of reform. Aztec mythos and religious practices, much like the Maya, were notoriously brutal. Human sacrifices were brought to the top of a temple pyramid where they could be closer to the heavens, and slain in honor of the gods—just as the moon goddess Coyolxauhqui died in her myth.

On a carved stone disc, similar to the Aztec Calendar, found in the Templo Mayor in present-day Mexico City, Coyolxauhqui is depicted after attempting to slay her mother, Coatlicue. Coatlicue had become miraculously pregnant, which enraged her children, including Coyolxauhqui, who plotted an attack against her. Just before the attack, Coatlicue suddenly gave birth to Huitzilopochtli as a fully grown man in full armor. He immediately avenged his mother, throwing Coyolxauhqui’s head into the sky to become the moon.

The Aztecs believed the god Huitzilopochtli protected the sun from darkness, similar to the way the Greeks viewed the god Helios. The Aztecs needed to feed Huitzilopochtli in order to keep the sun moving and prevent the world from being swallowed up by darkness. What did they feed Huitzilopochtli? Human hearts, of course.

The practice of sacrificing to Huitzilopochtli was considered an honor, one that ensured a pleasant afterlife. As with the Maya, the Aztecs understood the importance of human blood and that the heart was its source. On occasion, the Aztec people also consumed the flesh of sacrificial victims as another form of honor, often to worship the underworld god, Mictlantecuhtli.

Archaeologists and historians suspect that while most of these practices had religious purposes, they also served to maintain the reputation of the Aztec, warning neighboring groups against waging war. Nearby tribes, aware of their ferocious reputation, would think twice about trying to invade any Aztec territory. Some scholars suggest this brutality was a primary cause of their forced assimilation and conversion by the European colonists.

5. Mythology vs Modernity

Mesoamerican myths frequently revolved around the importance of blood and the cruelties of life. This brutality may seem excessive by today’s standards, but this was how Mesoamerican groups engaged with and understood the world around them. Religious practices like these reflected the high value placed on human life, and especially human blood, in a time when existence was incredibly deadly.

The ancient Mesoamerican world was filled with dangerous animals, people, and climates. Many of the ancient myths and stories we are familiar with today stem from people trying to explain the natural order and the dangers that came with living. As a result, the stories often turned gruesome. While these empires have long since faded away, their legacies live on as their descendants continue to tell those stories today.