Prohibition began on January 17, 1920, one year after the 18th Amendment banned the production and sale of alcohol or “intoxicating liquors.” The associated Volstead Act gave law enforcement the power to enforce the new amendment. These two acts culminated decades of effort by various groups to ban alcohol.

These groups believed banning alcohol in all forms would alleviate many different problems. The Temperance Movement’s efforts went back decades, with their primary belief banning alcohol could only help poverty and other issues. Most of the credit for Prohibition should go to different religious groups stating that alcohol caused immorality and criminality. Lastly, the Anti-Saloon League played its part in promoting saloons as ungodly or corrupt.

With Prohibition, the law of the land, it did little to slow most things alcohol. Instead, a new can of worms opened up, adding more problems. First, a glaring loophole existed that could still possess or consume alcohol. Also, the expected health, social, and financial changes never really happened.

Changes Wrought

Prohibition’s ratification had immediate effects. If anything, alcohol consumption increased. Within weeks, alcohol smuggling commenced-these gangs became known as bootleggers. People smuggled alcohol individually while more organized, efficient gangs ran massive operations. Gangsters like Al Capone or Meyer Lansky became famous for their wealth, power, and behavior. These gangs made millions but fought violently for distribution routes and territory.

Hidden bars called “speakeasies” appeared, serving banned alcohol. Sometimes hidden, often, these bars kept a low profile, hoping to avoid a police raid to confiscate their alcohol. People made beer and alcohol, called “bathtub gin,” at home, circumventing any laws.

Attitudes Change Again

As the 1920s progressed, America’s attitude towards Prohibition gradually changed. First seen as a victory, Prohibition’s cost socially and economically became apparent. The changes to banning alcohol sought by the Temperance Movement failed as crime still existed, people’s health didn’t improve, and social problems remained.

With alcohol banned, this led to the rise of other illegal substances. Morphine, known since the Civil War, and heroin got popular, especially among women, as social drinking was frowned upon. A syringe and carrying case could be carried discretely. Drugs, too, got banned by 1925, but many still used, buying their drugs from dealers and doctors.

A second significant strike against Prohibition came with the rise in crime. As mentioned, gangs rose fast as they smuggled alcohol in from Canada, international waters, and the Caribbean. Violence escalated, too, as gangs fought vicious wars for control. The most famous event was the 1929 Valentine’s Day Massacre in Chicago.

Besides their turf wars, the gangsters often paid off police and politicians. The mind-boggling amount of illegal money frequently just got too tempting. In some cities, like Fort Lauderdale and Boise, whole police departments were arrested for corruption or even being bootleggers! Corrupt police warned speakeasies before raids happened or took a day off as smugglers landed their illegal cargo. Some police banked enough money equaling fifty times their salaries.

The Volstead Act enabled the government to enforce Prohibition but didn’t anticipate how fast smuggling began or how big America was. Law enforcement couldn’t be everywhere. Despite adding more cops, enforcement agents, and the U.S. Coast Guard got swamped by numbers. In the Atlantic, smuggler ships anchored in international waters and unloaded alcohol to small boats that sped ashore. It took until a 1925 Supreme Court decision to extend Coast Guard authority up to thirty miles out to sea.

Money Talks

The 1929 Stock Market Crash added to America’s distaste of Prohibition. With that economic nosedive called the Great Depression, taxation suddenly became essential to the Federal government. Alcohol has always been a reliable revenue source. Since 1919, little money has gone to government coffers as gangsters have enriched themselves.

The numbers provide a better explanation. Before the Great War, 30 to 40 percent of the government’s income tax derived from alcohol taxes. Also, despite the Roaring 1920s, many jobs related to alcohol disappeared, stoking further resentment. A government panel found that about 500,000 jobs would be created if Prohibition was lifted.

The Calls Against

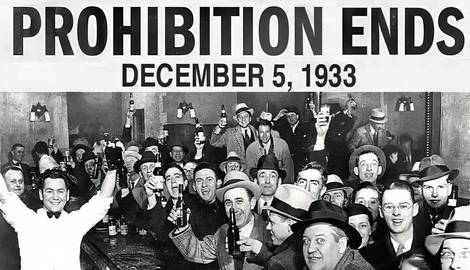

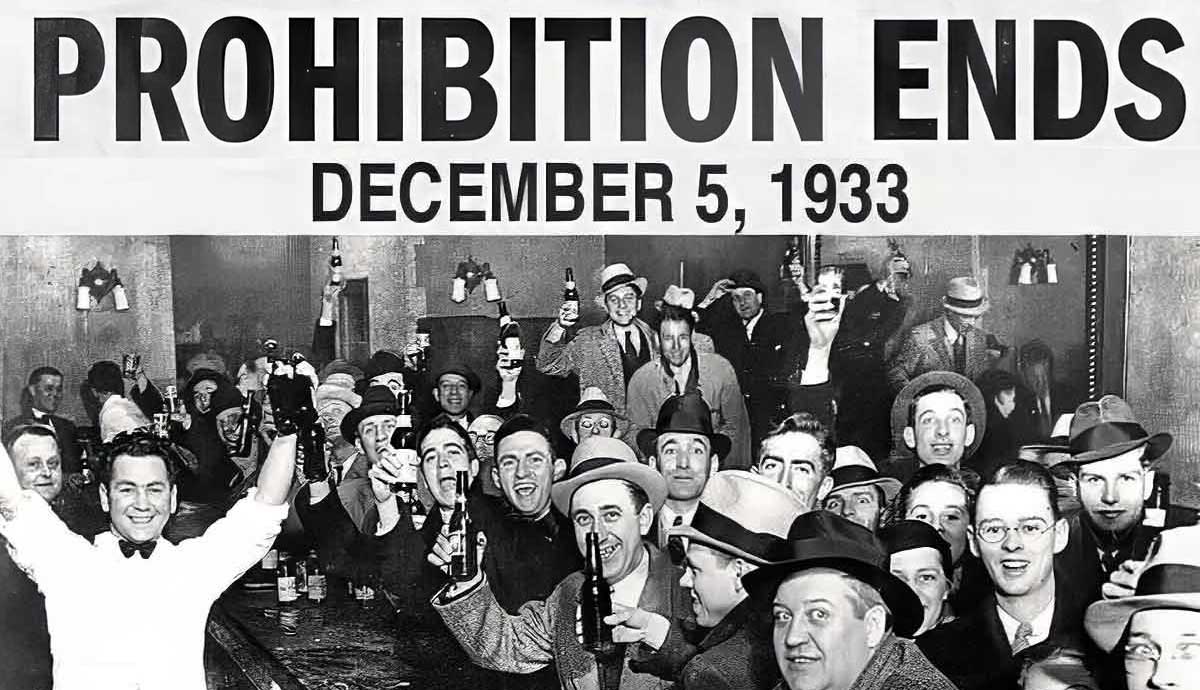

By 1930, the U.S. was mired in its deepest depression ever. Calls for repealing Prohibition grew louder, and politicians listened. In early 1933, people discussed this. Congress passed the 21st Amendment, ending Prohibition. Despite its intentions, Prohibition simply didn’t work. Even President Hoover called this a “noble experiment,” but a failed one at that.