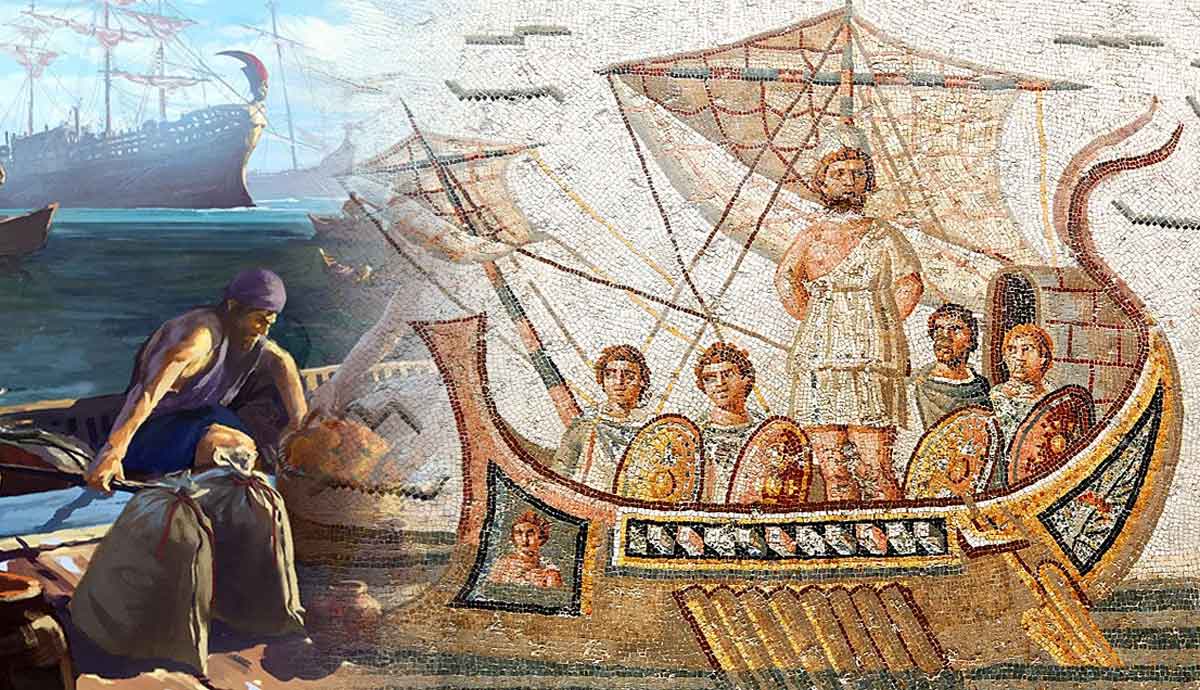

The Indian Ocean Trade route was one of the Roman Empire’s most lucrative long-distance trade routes. It was also the vital Roman link to the realms of the Far East, India and China. Each year, the ships laden with Mediterranean commodities would depart Egypt’s Red Sea ports and sail to India, bringing back exotic precious goods, such as spices, gems and silk. Indian Ocean Trade transformed Roman society, allowing the elites and commoners access to never-before-seen luxuries.

In fact, the demand for exotic commodities was so high that it drained Rome’s coffers. It also enriched those involved in the business, from merchants to the government. The long-distance trade would last for centuries, playing a major role in the cultural, religious, and diplomatic relations between the Roman Empire, India and China. However, the weakening of the Roman Empire’s economy, followed by the Arab conquests in the mid-seventh century, and most importantly, the loss of Egypt, brought an end to the Indian Ocean Trade.

Emperor Augustus Established Roman Indian Ocean Trade

Although the Indian Ocean Trade preceded Roman rule, it was only after Augustus’ annexation of Ptolemaic Egypt in 30 BCE that long-distance trade with the East became profitable. Emperor Augustus, who took Egypt as his personal property, removed the old Ptolemaic trade restrictions and ordered the legions to build roads through the desert. As a result, the goods could now travel quickly from the Mediterranean hub of Alexandria to the Red Sea ports of Berenike and Myos Hormos (and back). It also greatly increased the number of merchant vessels involved in the Indian Ocean trade. According to historian Strabo, the number of ships sailing to India during Augustus’ reign increased from 20 to over 120 vessels.

The Trade Route with India Increased the Prestige of the Roman Empire

Besides the growth of trade and commerce, the permanent route to India led to the establishment diplomatic contacts between the Roman Empire and the East. Already during Augustus’ reign, Indian ambassadors visited Rome to discuss an alliance with the emperor. The alliance had little impact, considering the enormous distance between the Mediterranean and the Indian Subcontinent.

However, the diplomatic contacts with the far-flung foreign lands left a mark on the ideology of the nascent Roman Empire, further solidifying emperor Augustus’ legitimacy. Although Roman legions never set foot on the Indian land, Augustus could use the oriental embassies to promote the idea of “Imperium sine fine” — “an empire without an end”. This ideology is best reflected in the famous ancient atlas known as the Ptolemy world’s Map.

The Roman Trade with the East is Described in the “Periplus of the Erythraean Sea”

Our primary source for the Roman Indian Ocean Trade is the “Periplus of the Erythraean Sea.” Written in 50 AD, this ancient navigation manual describes in detail the passage through the Red Sea and beyond. The Roman ships crossed the Indian Ocean with the help of the seasonal monsoons.

After reaching India, the ships stopped in Barbaricum (near modern-day Karachi, Pakistan) and Muziris, located at the Malabar Coast. Going further south, the Romans would reach the island of Taprobane (present-day Sri Lanka), whose ports acted as the transit hub for trade with Southeast Asia and China. The journey from Egypt to India and back took a year, while one-way crossing the open waters of the Indian Ocean lasted two weeks.

The Indian Ocean Route Brought Silk to Rome

Since Crassus’ disaster at Carrhae in 53 BC, the Roman expansion in the East came to a halt. Except for the brief Trajan’s campaign, Rome’s oriental ambitions and the establishment of the land connection to India and China were checked by its main rival – Parthia. However, the Indian Ocean sea lane bypassed Parthia as the intermediary, allowing the Romans to reach Indian ports and venture beyond. Roman traders sailed to the coast of modern-day Vietnam (then under Chinese control), establishing a direct connection with Han China. China was vital in the silk trade, and by the second century, silk, a rarity in Republican Rome, became a common sight in the Empire. In fact, the luxury commodity was in such demand that Pliny the Elder blamed silk for putting a strain on the Roman economy.

Indian Ocean Trade was Made on a Large Scale

The Indian Ocean trade and the silk trade resulted in a significant outflow of wealth during the first two centuries of the Roman Empire. Its extent is reflected in the large hoards of Roman coins found throughout India, especially in the busy southern ports. In addition, smaller amounts of imperial coinage have been found in Vietnam, China, and even Korea, further confirming the Indian merchants’ role as intermediaries between the two mighty empires of Rome and China. The enormous extent of the Indian Ocean Trade is further reflected in the shipwreck of a massive Roman cargo ship found near Madrague de Giens, off the southern coast of France. The 40 meters (130 feet) long, two-mast merchantman carried between 5 000 to 8 000 amphorae, weighing up to 400 tons.

The End of the Roman Indian Ocean Trade

While the deadly pandemic outbreak – the Antonine Plague – weakened the Roman economy, the Indian Ocean Trade continued, albeit on a smaller scale. In “Christian Topography,” the sixth-century monk and former merchant Cosmas Indicopleustes described his sea voyage to India and Taprobane in detail. Around the same time, the Romans smuggled silkworm eggs to Constantinople (what was Constantinople), establishing a silk monopoly in Europe for centuries to come. Yet, trade with the East abruptly halted in the mid-seventh century. After the disaster at Yarmuk (what was Yarmuk), much of the Empire’s eastern provinces, including Egypt, fell into the hands of the Arabic invaders. The loss of Egypt and its Red Sea ports ended 670 years of Roman trade with India and China.

The brief Chinese attempt to restart trade on the high seas under the Ming dynasty also failed following the death of admiral Zheng He. Only in the fifteenth century, after the Ottoman Turks cut off all the land routes to the East, would the Europeans set sails to India, ushering in the new era of Indian Ocean Trade in the Age of Discovery.