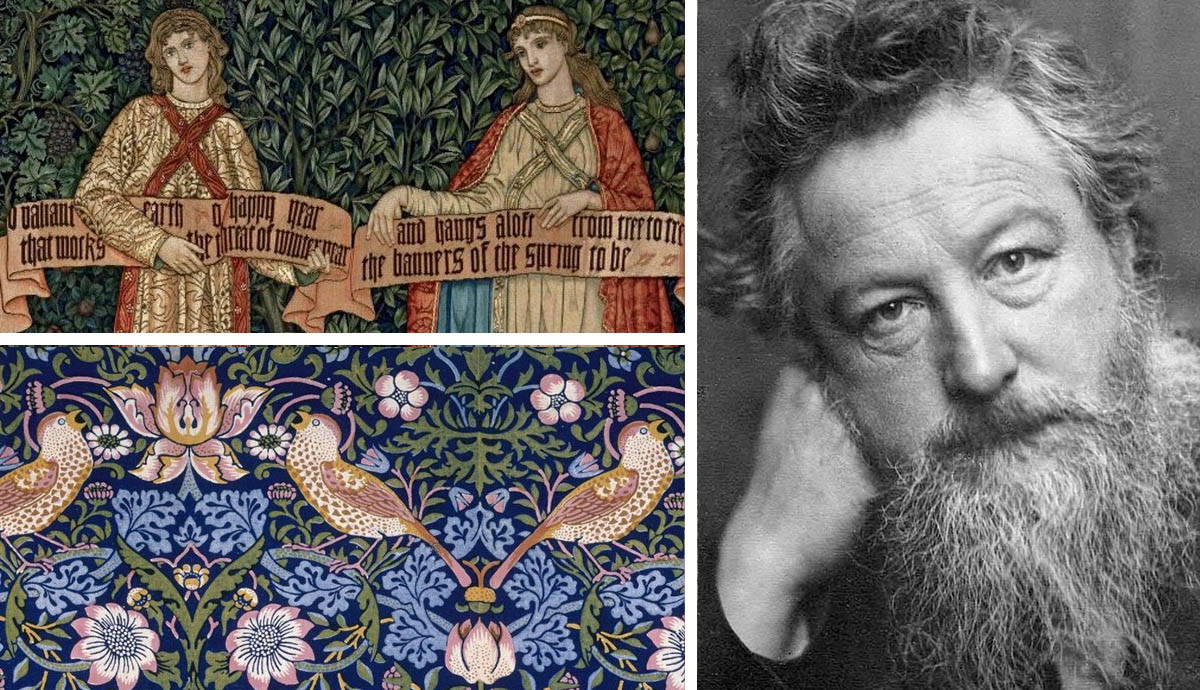

William Morris was a Victorian-era tastemaker who is often remembered by his most famous quote: “Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.” (Morris, 1880) Over the course of his storied career, Morris designed hundreds of intricate wallpaper patterns and textile art in his signature handcrafted style, wrote poetry and novels, and made waves as a political activist. Here are seven fascinating facts—paired with seven iconic William Morris designs—that demonstrate the artist’s lasting legacy from the advent of the nineteenth-century Arts and Crafts Movement in Great Britain to modern-day interior design around the world.

William Morris’s Idyllic Childhood and Oxford Education

Born in Walthamstow, East London in 1834, William Morris was the third of nine children born to a wealthy family. He enjoyed a carefree childhood in the English countryside and a prestigious private education. As a young adult, Morris entered Exeter College at Oxford to study theology. Soon he was swayed by the writings of art critic John Ruskin, who argued that artists should observe nature rather than copying the Old Masters, as was standard practice for fine artists in academic training. Morris was also enchanted by the medieval history and charm that Oxford had to offer, and increasingly disenchanted by the Church of England, ultimately deciding to pursue a life of art instead of religion.

While at university, Morris formed lifelong friendships with Pre-Raphaelite artists Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones. As students, they were commissioned by John Ruskin to paint murals, inspired by the medieval tales of King Arthur as told by Alfred Lord Tennyson, for the Oxford Student Union. One of the models for this project, Jane Burden, caught the attention of both Rossetti and Morris. While she ultimately married William Morris, Jane maintained an intimate relationship with Rossetti for decades, which Morris reluctantly accepted.

William Morris: Pioneer of the Arts and Crafts Movement

Perhaps the most significant of William Morris’s many accomplishments is his hand in founding the Arts and Crafts Movement in Victorian era Britain. The chief aim of this movement was to reform the trajectory of design and décor which, according to Morris, lacked quality and integrity due to factory production. The Arts and Crafts Movement revived traditional textile art techniques that had been made obsolete by machinery, including hand embroidery, weaving, and natural dyeing. It also sought to elevate the status of craftspeople and folk artists, who for centuries had been ranked at the bottom of the hierarchy of fine art, or whose artistic contributions had been altogether ignored in the creation of furnishings and decorative objects.

The philosophies and aesthetics of William Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement quickly gained popularity throughout Europe and in the United States through the start of the twentieth century. While the rise of Modernism ultimately surpassed the Arts and Crafts Movement in mainstream popularity, interior designers still recognize its vital influence today.

Medievalism Over Modernity In The Industrial Revolution

“Apart from the desire to produce beautiful things,” wrote William Morris, “the leading passion in my life has been and is hatred of modern civilization.” Instead of embracing the lifestyle and cultural norms brought about by the Industrial Revolution, Morris was driven by his nostalgia for the Middle Ages, which he believed was more communal and connected to nature than Victorian-era society. He immersed himself in the Old Norse sagas, the chivalrous legends of King Arthur, and the plays of William Shakespeare for inspiration.

Morris also rejected the popular interior decorating trends of his day. He believed mainstream textile art and household goods strayed too far from the design principle “form follows function,” which dictates that the shape and look of an object should directly relate to its intended use, and that designers should embrace the inherent qualities of the materials they used instead of disguising them with excessive ornamentation. Through research and travel to historical sites, William Morris found that medieval craftsmanship better embodied the aims of the Arts and Crafts Movement.

Morris & Company: Revolutionizing Domestic Textile Art

William Morris’s first interior design firm—Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Company—changed the landscape of domestic decorating in Victorian-era Britain and beyond. He joined forces with members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and other craftspeople who shared his passion for traditional techniques and handmade décor inspired by nature and medieval aesthetics. Together, they created their own workshop, where they used old-fashioned processes and natural materials to produce beautiful household goods by hand, including furniture, textile art, wallpaper, and Gothic Revival stained glass.

Morris became involved in both the intellectual design and physical manufacturing processes because he believed that the separation of these processes had contributed to a decline in standards.

The firm, which would later be restructured as Morris & Company, received several significant decorating commissions over the course of its run, including the “Green Dining Room” at the South Kensington Museum (later renamed the Victoria & Albert Museum) in London, where Morris also lent his expertise as an acquisitions consultant. William Morris also designed every inch of the homes he and his family lived in, including the Red House and Kelmscott Manor. His original wallpaper and textile art designs are still sold worldwide under the name Morris & Co. today.

The Magnificent Manuscripts Of Kelmscott Press

Towards the end of his career, William Morris founded Kelmscott Press with the goal to create his ideal version of a book by reviving the medieval practice of manuscript illumination and the simple mechanics of the original Gutenberg Press. Kelmscott Press went on to produce over twenty thousand original copies of over fifty titles, including Morris’s own poetry and novels. Exactly as Morris envisioned, every book published by the Kelmscott Press is clearly unified, sharing the same kind of paper, ink, typefaces, and complementary decorative motifs.

William Morris spent four years laboring over the Kelmscott Press’s most famous publication, The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, now newly imprinted. The Kelmscott Chaucer is an immaculately decorated book that features fully-illuminated pages, timeless gothic typefaces that Morris designed himself, and dozens of wood-cut illustrations by Edward Burne-Jones, who aptly called the book a “pocket cathedral.”

Art For All: William Morris’s Political Activism

William Morris’s philosophies about art and his political beliefs were thoroughly intertwined. He was staunchly opposed to the ugliness of modern visual culture and the ugliness of social injustice. As a socialist activist, Morris believed that the Industrial Revolution, and the resulting rise of capitalism and wage labor, was robbing workers of their creativity, access to art, and quality of life. He was inspired by the advent of Marxism and once declared, “I do not want art for a few any more than education for a few, or freedom for a few.” (Morris, 1882)

Morris helped form the Socialist League in Britain, opening up the coach house at his residence as the meeting place for the group. He also published various writings—from a political manifesto to a soft science fiction novel—about socialism, ignoring colleagues who warned that sharing his polarizing beliefs might negatively affect his success as an artist. However, William Morris’s public political activism actually helped increase the acceptance of socialist ideology in Great Britain and remains a key part of his legacy.

Artistic Influence In The Family Of William Morris

William Morris was not the only member of his immediate family to exact lasting influence on the art of Victorian-era Britain. His wife, Jane Burden, was herself a practiced embroiderer who lent her skills to many of the firm’s textile art projects. She was also one of the most famous muses of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood—especially Dante Gabriel Rossetti—who was struck by her sensual beauty and strong, androgynous features. Despite lacking confidence at figure painting, even William Morris painted a portrait of Jane Burden, working for months to perfect the intricate details throughout the composition. This was the only painting Morris ever actually completed.

William Morris’s daughter, May Morris, was also a prolific designer in her own right. At just twenty-three years old, May Morris led the embroidery arm of Morris and Co. and produced several of her own wallpaper and textile designs. Additionally, May Morris ensured her father’s legacy as the leader of the Arts and Crafts Movement was celebrated long after his death by completing important biographical work and bequeathing his art to museum collections that could preserve and exhibit it.