Many conventions from historical, Western societies have been patriarchal in nature. However, while Celtic society was certainly still male-dominated, Celtic women—depending on the social class they were born into—were often afforded access to wealth and even training as warriors. They were figureheads, leaders, mothers, and healers. Additionally, many of the most important figures in Celtic mythology were female goddesses.

Celtic goddesses were often associated with fertility, childbirth, and the cycles of nature. Many goddesses presided over natural resources, such as rivers and forests. The natural world was incredibly significant to Celtic peoples, who revered their surrounding landscape and often integrated it into their ritual practices. As such, women—both real and mythological—were incredibly important in the Celtic world.

Sources of Knowledge on Women in Celtic Society

What we know about Celtic society is largely based on archaeological evidence, rather than textual sources. Celtic peoples did not produce many written sources, as they were a predominantly oral culture. Most textual sources from the period documenting accounts of Celtic peoples, therefore, come from their Greek and Roman neighbors.

These sources are typically travel narratives and war narratives and are relatively unconcerned with describing the inner workings of Celtic society. Rather, they are primarily interested in characterizing Celtic peoples as barbarians. This characterization positioned the Celts as inherently different from the ancient Greeks and Romans and justified the imperial expansion that occurred during the transition from the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire.

What does this mean for our knowledge about Celtic women? What we do know about Celtic women from textual sources comes largely from these biased narratives. Many of these sources have been called into question in more recent scholarship.

For example, Strabo mentions a Celtic tribe in which the “Men and women dance together, holding each other’s hands,” which was unusual among Mediterranean peoples. He states that the position of the sexes relative to each other is “opposite… to how it is with us.” Evidently, Strabo’s intention may have been to describe how Celtic peoples were the opposite of the Romans, rather than to describe their social interactions as they may have truly been.

A truer image of the various roles women may have occupied in Celtic society can be pieced together from archaeological evidence. Based on evidence from graves, as well as general domestic settlements, we know that women were responsible for child-rearing, most healing practices, and the maintenance of the home. This much is also recorded by ancient authors.

There is also evidence of some level of female involvement in the warrior class. However, there is no significant evidence to suggest that women were wholly equal to men in Celtic society: Caesar wrote that men had the power of life and death over their wives, as well as their children. The position of women in Celtic society, however, is nevertheless an interesting topic of inquiry.

Social Status and Wealth: How High Could Women Climb?

All the archaeological and literary evidence suggests that Celtic society was hierarchical and stratified into classes based on honor and status. There was an unfree class—taking the form of slaves and prisoners of war—and a free class, who were able to exist freely but fell under the authority of more elite individuals.

Higher-class individuals included druids, bards, and prophets—all religious figures—and potentially craftsmen, and of course, the king and his family. The possibility of women holding high social status in their own right, rather than by virtue of their male relatives, varied throughout the Celtic world. By and large, elite women achieved their status through their connection to elite male counterparts. Their wealth would not have been limited in any way, and some of the richest burials from Iron Age Europe clearly belonged to women.

Furthermore, in the 1st century CE in Britain two tribes—the Iceni and the Brigantes—were ruled by queens: Boudica and Cartimandua, respectively. By the Early Medieval Period, however, women’s abilities to obtain this high social status accompanied by independent legal rights had faded away.

Women’s graves signify just how wealthy elite Celtic women were: they are often found surrounded by hairpins, cast bronze torcs (thick necklaces often associated with Celtic warriors and elites), necklaces of beads made of glass, amber, bone, horn, agate, and bronze, arm rings, bracelets, armlets for the forearms, and anklets.

The Vix Grave from modern France is the most famous rich female burial to be found to date. A huge bronze mixing bowl, known as the Vix Krater, indicates the status of the woman buried there. The grave was interpreted as belonging to a woman because of the high volume of jewelry and the assemblage of imported objects from Italy and Greece associated with the preparation of wine. The presence of jewelry would not have been an automatic indicator that a grave belonged to a woman, as men also wore jewelry, but the amount and type of jewelry may have signified a female owner.

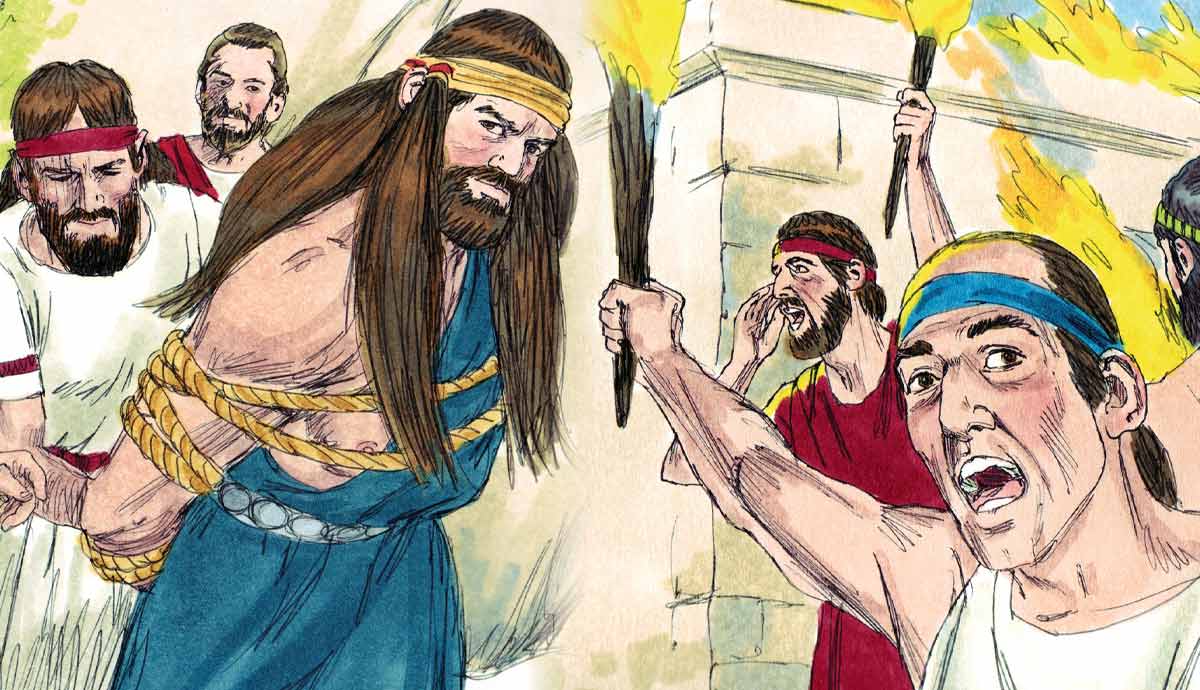

Women as Warriors

Likely the most famous of Celtic woman was Boudica, the aforementioned warrior queen of the Iceni. Cassius Dio described Boudica in his Roman History. He wrote:

“But the person who was chiefly instrumental in rousing the natives and persuading them to fight the Romans, the person who was thought worthy to be their leader and who directed the conduct of the entire war, was Buduica, a Briton woman of the royal family and possessed of greater intelligence than often belongs to women… In stature she was very tall, in appearance most terrifying, in the glance of her eye most fierce, and her voice was harsh; a great mass of the tawniest hair fell to her hips; around her neck was a large golden necklace; and she wore a tunic of diverse colors over which a thick mantle was fastened with a brooch. This was her invariable attire.”

Dio clearly identifies that Boudica was unique. His description, however, is like other ancient writers’ descriptions of unnamed Celtic warrior women. In Book V of his Historical Library, Diodorus Siculus wrote, “The women of the Gauls are not only like men in their great stature, but they are a match for them in courage as well.”

And Plutarch:

“Here the women met them holding swords and axes in their hands. With hideous shrieks of rage, they tried to drive back the hunted and the hunters. The fugitives as deserters, the pursuers as foes. With bare hands the women tore away the shields of the Romans or grasped their swords, enduring mutilating wounds.”

Quotes from ancient writers such as this present evidence that Celtic women were trained in the use of weapons, and likely in battle tactics as well. However, these sources should be interrogated: were they just exaggerating the involvement of women in war to justify imperial expansion over barbaric people? There is, on the other hand, a significant minority of weapons burials from Iron Age Britain that are believed to be for female warriors, which provide archaeological support for these written claims.

Female Celtic Goddesses

The Celtic peoples did not have one clearly defined pantheon of gods — “Celtic” is an umbrella term that refers to peoples living across Europe over a large span of time. However, there are a few major deities that are consistent across Celtic mythology. Many of the Celtic deities are goddesses, and often their domain is associated with nature. For instance, Brigid is the Celtic goddess of poetry, healing, fire, smithcraft, and fertility.

Brigid is still celebrated on Imbolc, a pagan holiday that originated from the Celts and marks the halfway point between the winter solstice and the vernal equinox. The word imbolc means “in the belly of the Mother,” because the seeds of spring are beginning to stir in the belly of Mother Earth.

Over the years, Brigid was adopted by Christianity as St. Brigid. Brigid (or Bridget) is the patron saint of Irish nuns, newborns, midwives, dairy maids, and cattle. The stories of St. Brigid and the goddess Brigid are very similar. Both are associated with milk, fire, the home, and babies.

Another important Celtic goddess is the Morrigan, goddess of war and fate. The Morrigan was said to appear on the battlefield before important battles, predicting the outcome and sometimes choosing who would live or die.

The goddess Epona, on the other hand, was the goddess of horses. She was believed to protect horses and riders. Epona was also associated with fertility and abundance, and her worship was particularly popular among the Gaulish and Roman cavalry. She was seen as a protector of the natural world and was associated with the cycles of life and death.

Lastly, a major Celtic goddess—and one particularly associated with nature—was Danu, the mother goddess of the Tuatha Dé Danann, the ancient Irish gods and goddesses. She was believed to be the mother of all the gods and was associated with fertility, motherhood, and the cycles of nature. Because Danu was associated with nature and nurturing, she was also associated with the land and the natural world, which included agriculture.

Depictions of Celtic Women

Depictions of Celtic peoples, particularly those rendered by Celtic artists, are rare. Even rarer are depictions of Celtic women. Most depictions of Celtic women that we do have are either ancient Roman or Gallo-Roman depictions, and the women are depicted in the standard Roman style. In these images, women are often shown wearing headdresses rather than bareheaded, so while we know little about typical forms of Celtic female hairstyling, we know that higher-class women, at least, likely wore headdresses.

References to what Celtic women looked like often serve to characterize them as barbaric. As per Dio’s quote about Boudica, referenced earlier: “In stature she was very tall, in appearance most terrifying … a great mass of the tawniest hair fell to her hips; around her neck was a large golden necklace; and she wore a tunic of diverse colors.”

Diodorus Siculus wrote that Celtic men and women wore clothing made from very colorful cloth, often with a gold-embroidered outer layer, and held together with golden fibulae. The women’s tunic was longer than the men’s, and a leather or metal belt (sometimes a chain) was tied around the waist. Archaeological finds in female burials present significant evidence that elite Celtic women wore a lot of gold and bronze jewelry including hairpins, brooches, necklaces, bracelets, arm rings, barrel-shaped armlets, and anklets.

Bibliography

Green, M. (1996). The Celtic World. Routledge.

Maier, B. (2018). The Celts: A History from Earliest Times to the Present. Edinburgh University Press.