Originally a secondary tool for philosophers and grammarians, logic was exalted into new primary status in the 19th and 20th centuries. When analytic philosophers and mathematicians raised the stakes, they concluded that logic was not secondary but was actually the foundation of arithmetic. Being in the middle of philosophy and mathematics—two disciplines notorious for their gender gap—female logicians were as scarce as hen’s teeth. Who were some of these women and their contributions?

Women Making History in the Field of Logic

“That women are not logical is one of the recognized conventions of social life” is the opening sentence of one of the many articles written by males that emphasize that women are emotional while men are logical. This further meant that they would not make good logicians or philosophers of mathematics and language, but they should be allowed to excel in ethics or political and social philosophy because they are natural caretakers.

As crazy as it sounds, such argumentative lines can be found in academic literature as recently as 2014. Luckily, however, a quick overview of the history of 19th and 20th-century logic reveals important female figures whose contributions have both scientific and existential aspects, given that they managed to leave their mark despite academic discrimination and bias. In what follows, we explore the work of five female logicians at the intersection of philosophy and mathematics as well as philosophy and language. It is worth noting, however, that many female mathematicians also had a hand in developing logic during the same period and equally struggled as their peers in philosophy.

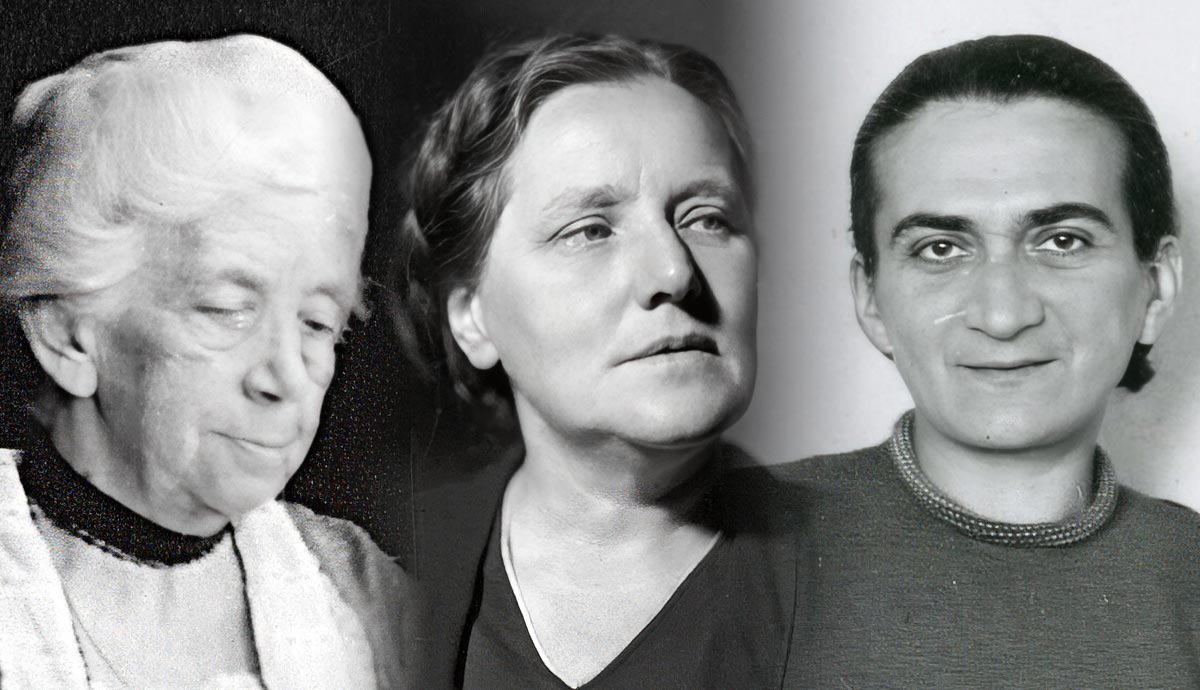

1. Christine Ladd-Franklin

It is quite hard to classify Christine Ladd-Franklin (1847-1930): she was an experimental or natural philosopher, psychologist, logician, and mathematician, or simply everything that was forbidden for her sex in 19th century America. She was the first woman with a PhD in logic whose supervisor was none other than Charles Sander Peirce, one of the most competent and talented (and misunderstood) savants of the century, and with a membership in the American Psychological Association as well as the Optical Society of America.

What’s even more funny is that she wanted to be an astronomer, but women were forbidden to do work in laboratories or observatories back then. She was a valedictorian at Wesleyan Academy and then managed to enroll in Vassar College but had to resign due to financial issues. She eventually finished her BA studies in 1869. It was only in 1878 that she was accepted at John Hopkins University after having contributed 77 mathematical problems and solutions for the London-based Educational Times journal and published nine papers in mathematics journals.

At Johns Hopkins, she was treated horrendously from the very start: she was not allowed to hold the title of “fellow,” nor was her name ever printed with those of other fellows in any university circular or newsletter. Nonetheless, this did not discourage her even a bit. Ladd-Franklin published her dissertation in modern formal logic and completed all requirements by 1883, although the university refused to award her PhD for fear that other women would follow her lead.

For a long time, she was denied any academic position and only in 1904 managed to secure one class per academic year at Johns Hopkins. For all these reasons, and probably because at the turn of the 20th century, women were not shunned as much from laboratories, Ladd-Franklin focused on psychology of color perception and worked with the esteemed physicist and psychologist Herman Helmholtz.

2. Susan Stebbing

Susan Stebbing (1885-1943) was the first female in many endeavors in 20th century English academia. Thus, she was the first woman to hold a chair in philosophy in Great Britain and the first female founder and chief editor of an Anglophone philosophical journal, Analysis. First trained as a historian at Cambridge, she was fascinated by the works of English philosopher Francis Herbert Bradley, so she decided to pursue a philosophy degree instead. She was awarded an MA in philosophy with distinction and proceeded to become a reader or lecturer at colleges across London. After receiving her PhD in 1931, she obtained the title of full professor at London University and Bedford College. The Susan Stebbing Studentship now offers a yearly stipend to a female graduate student in Philosophy at King’s College London, where a chair of philosophy is also named in her honor.

Stebbing’s first significant book, A Modern Introduction to Logic (1930), provided a much-needed bridge between traditional Aristotelian logic and new mathematical logic, which is particularly associated with the work of Gottlob Frege and Bertrand Russell. The book was still reprinted in the 1960s and acclaimed as one of the best overviews of modern logic. In 1934, Stebbing published another book, Logic in Practice, which was aimed at a wider audience and can be considered one of the first self-help books since Stebbing wanted people to learn how to reason correctly. In 1939, her book Thinking to Some Purpose, a full-blown manual for critical and clear thinking, saw the light of the day. Stebbing was concerned with the political and social turmoil on the brink of World War II and recognized the need for preserving democratic values through diminishing “unconscious bias” and “unrecognized ignorance.”

3. Ruth Barcan Marcus

Ruth Barcan Marcus (1921-2012) challenged two things considered classic: namely, classical logic and the stereotype of the male expert who revolutionized logic and mathematics. Barcan Marcus obtained her BA in philosophy and mathematics at New York University in 1941, as well as her MA and PhD at Yale University in 1942 and 1946, respectively. Her PhD thesis was titled Strict Functional Calculus. Barcan Marcus went on to teach across the USA, settling for the position at her alma mater, Yale, where she was working as an emerita until 1992. After retirement, the tireless lady taught at the University of California, Irvine.

Barcan Marcus worked on quantified modal logic, which was considered somewhat controversial during the 1940s as it was more based on the analysis of natural language than formal orientation in classical logic. Modal logic concerns operators such as “possibly” and “necessarily.” Between 1946 and 1947, a 25-year-old changed the face of logic by introducing the famous Barcan formula, which can be informally read as the following conditional: if possibly something is A, then something is possibly A. She further developed the semantics of quantified modal logic and extended her work into the philosophy of language.

Barcan Marcus put forward the tag theory of proper names in her paper “Modalities and Intensional Languages,” published in 1961 in the journal Synthese. The core idea of her theory is that the meaning of names is exhausted in their referential functions or that it’s a mere tag without descriptive content. Later, a controversy ensued over the possibility that her theory of proper names was plagiarized by her much more celebrated colleague and wunderkind Saul Kripke.

4. Rose (Rozalia) Rand

Rose Rand (1903-1980) was born in what is now Lviv, Ukraine, but later studied in Vienna under big names like Moritz Schlick and Rudolf Carnap. During her PhD studies between 1930 and 1935, she was an active member of the Vienna Circle, and she even kept records of meetings. In 1938 she was awarded a PhD but never got to become a university professor due to her Jewish ancestry—racial laws were underway after the Anschluss or Nazi Germany’s annexation of Austria.

Rand’s first paper was published in 1939 in Internationale Zeitschrift für Theorie des Rechts and was well ahead of her time since it marked the beginning of deontic logic, a field concerned with the formalization of norms. However, due to the paper being written in German, it was overlooked by many logicians in the Anglophone world, so Rand did not receive any credits for her pioneering work. This was, unfortunately, only one of many misfortunes that struck her.

With the generous help of Susan Stabbing, Rand emigrated to London in 1939 but had to resign from her studies in 1943 as a foreign citizen with no nationality. She managed to obtain a small research grant at Oxford University due to Karl Popper’s influence in Great Britain. She emigrated once again in 1954 to the USA so that she could finally land a job in academia. There she managed to find only temporary positions as a research associate or teacher of logic, but mostly worked as a freelance translator from Polish to English. Her papers, unpublished manuscripts, research drafts, translations of notable Polish logicians from Lviv-Warsaw School, and correspondence with other members of the Vienna Circle are kept in archives at the University of Pittsburgh.

5. Elizabeth Anscombe

Elizabeth Anscombe (1919-2001), a Cambridge-affiliated professor of philosophy, was one of the most famous female voices of early analytic philosophy and logic. One anecdote that illustrates her relentless character occurred in a Boston restaurant where she was told that ladies do not wear trousers. In response, she boldly removed them in front of all the guests. Anscombe is not your typical woman in academia: she was a fervent Catholic, which also meant that she was against abortion and contraception, and had seven children with her husband, famous British philosopher Peter Geach. Wittgenstein described her as one of his favorite and brightest students and addressed her with the pet name “old man” (yup, Wittgenstein was not much of a fan of female academics).

Her philosophical scope is impressively wide—from translating and commenting on Wittgenstein, moral philosophy and action theory, metaphysics, epistemology, and more formal stuff. However, only her contributions to philosophical logic will be mentioned here.

In her book Introduction to Wittgenstein’s Tractatus (1959) and paper “Making True” (1982), Anscombe was perplexed by the truth values of propositions, or precisely, what elements constitute their truthfulness or falseness. Her method may come across as peculiar since she was following Wittgenstein in his analysis of ordinary language and believed that conceptual analysis can be applied even in the context of formal logic. Anscombe turned the tables and dissected formal notions like disjunction and its truth values from the perspective of ordinary language sentences despite the efforts of those like Frege and Russell who were obsessed with perfect formal language freed from any ambiguities of natural language.