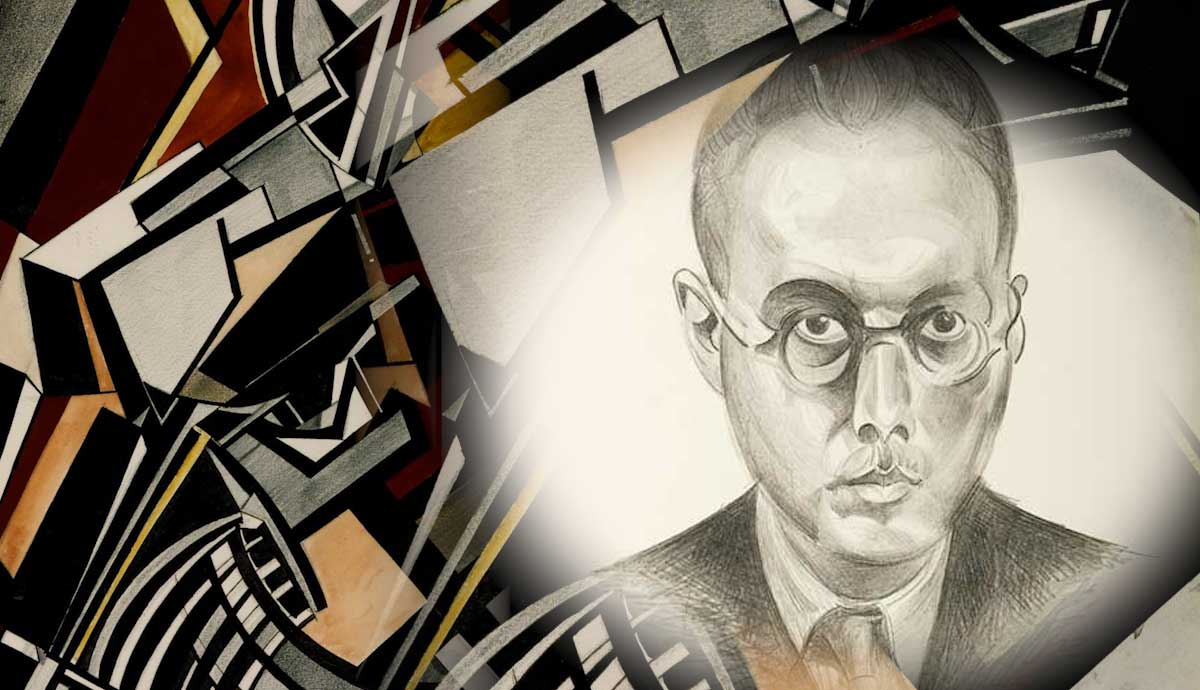

Wyndham Lewis was a controversial figure both in his own lifetime and for modern audiences. He founded Vorticism, pioneered new artistic philosophies, became a respected portrait artist, and wrote Tarr, which is now considered one of the most important novels of English literary modernism. He was also belligerent and wilfully aggressive in his critiques of his contemporary artists and writers – including his own friends. Not only this, but he was also among the artists of his generation who embraced fascism and penned the first pro-Hitler book to be written in English.

Wyndham Lewis: The Early Years

The story of Wyndham Lewis’ birth is suitably extraordinary. Percy Wyndham Lewis was born on 18 November 1882 on his wealthy American father’s yacht (which was named ‘Wanda’) off the shores of Nova Scotia, Canada.

His parents separated around 1893, and his English mother returned to England with the young Lewis in tow. He was educated at the elite Rugby School and then went on to study at the Slade School of Fine Art among artists such as David Bomberg, Dora Carrington, Paul Nash, and Stanley Spencer. In 1902, however, he was expelled from the Slade. Swapping his studies for traveling, he made his way through Europe, spending most of his time in Paris, where he studied art.

Returning to London: Camden & Bloomsbury

In 1908, he returned to England and settled in London. Here, he became a founding member of the Camden Town Group of artists and was in regular contact with other London-based literary and artistic groups, the most notable perhaps being the Bloomsbury Group.

As was typical of Lewis, he had a turbulent relationship with the Bloomsbury Group. However, it was through one of the Bloomsbury Group’s most notable members, Roger Fry, that some of Lewis’ work was displayed in the Second Post-Impressionist exhibition of 1912. And in the same year, he received a commission to design and create art objects, including a mural and a drop curtain, for The Cave of the Golden Calf, an avant-garde cabaret and nightclub located on London’s Heddon Street.

In 1913, Roger Fry, Vanessa Bell, and Duncan Grant set up the Omega Workshops. The objective here was to bring a Post-Impressionist aesthetic into people’s homes by creating beautiful yet practical decorative objects, such as rugs, textiles, trays, lamps and lampshades, and furniture. In addition, the Omega Workshops provided progressive young artists with salaried work, enabling them to pursue their own artistic projects in their spare time. Among these progressive young artists was Wyndham Lewis.

Vorticism

By 1914, however, Lewis – along with a group of other dissenting Omega artists such as Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Frederick Etchells, Cuthbert Hamilton, and Edward Wadsworth – had left the Omega in what has come to be known as the ideal homes rumpus. Leaving the Omega behind, they set up the Rebel Art Centre at 38 Great Ormond Street, London. Conceived as a direct rival to the Omega Workshops, the Rebel Art Centre was to last just four months.

Despite the brevity of the Rebel Art Centre, the artists grouped there went on to form Vorticism, an avant-garde movement that aimed to embrace elements of both Cubism and Futurism. In typical Wyndham Lewis fashion, he was highly critical of aspects of both of these movements and sought to combine elements of which he approved while casting out those of which he did not.

To Lewis’ mind, Cubism had discovered a means of visually depicting the fragmentation of modernity, though it lacked vitality. Futurism, on the other hand, captured the dynamism of the modern machine age, but it was too straightforwardly exalting in its attitude towards mechanization, thus ignoring the darker aspects of life in an industrial city, such as Vorticism’s native London.

The aims of Vorticism were laid out in BLAST, a magazine that was chiefly Lewis’ project, though it did feature articles by Ford Madox Ford and Rebecca West, poetry by Ezra Pound, and reproductions of Vorticist artworks by Lewis, Wadsworth, Etchells, Jacob Epstein, Hamilton, and Gaudier-Brzeska. A month after its release, however, Britain declared war on Germany, and by the time BLAST’s second issue was printed, the movement was in disarray. Gaudier-Brzeska had died serving in the trenches in his native France, while other members, including Lewis, Roberts, and Wadsworth, had signed up to fight on the frontline, too.

The War Years

Lewis spent the first part of the war on the Western Front, where he served as a second lieutenant in the Royal Artillery. Following the Battle of Passchendaele in 1917, he was made an official war artist for both the British and Canadian governments. Although Lewis and other official war artists were tasked with creating representational artworks that would help document the war experience, he nonetheless contrived to incorporate a more modernist aesthetic into his paintings during this time. That it was an artistically fruitful time for Lewis, despite the carnage and destruction of the war, is evident from the fact that in 1918 he held an exhibition of his wartime artworks under the title “Guns.”

It was also during the war that Tarr – possibly Lewis’ most famous novel – was published serially in The Egoist from April 1916 to November 1917. An important magazine in modernist print culture, by this point, The Egoist had already printed James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and would go on to print three and a half sections of his Ulysses, as well as T. S. Eliot’s famous essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent.” Tarr was then published as a printed book in 1918 and is now considered one of English modernism’s most significant prose works.

The Writing Twenties

Wyndham Lewis began the 1920s by forming Group X. Among the members of Group X were many artists who had been part of the Vorticist movement, such as Jessica Dismorr, Etchells, Roberts, Wadsworth, and Hamilton. Though it was intended to take something of an avant-garde stand against the return to a more conservative, representational style of painting (known as the “return to order”) that prevailed following the end of the First World War, Group X lacked the aesthetic unity of Vorticism.

While William Roberts pioneered his own distinctive Cubist-inspired style of painting, the other members of Group X – including Lewis – began to incorporate their more radical artistic tendencies within more visually traditional works in the interest of saleability.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Group X was a short-lived venture of Lewis’. Nonetheless, in 1921, he secured a major exhibition, “Tyros and Portraits,” at Leicester Galleries. The only paintings exhibited here to have survived are A Reading of Ovid and Mr. Wyndham Lewis as a Tyro. Caricatures intended to satirize elements of the new and distorted culture that emerged following the end of the First World War; Tyros were Lewis’ own invention and came to animate his artistic output in this decade. He subsequently launched his second magazine, The Tyro.

Like BLAST before it, The Tyro only ran for two issues, the second of which contained Lewis’ “Essay on the Objective of Plastic Art in our Time.” This is widely considered to be Lewis’ key declaration of his artistic philosophy.

The late 1920s, however, were marked by a shift in Lewis’ creative focus as he turned his attention to writing rather than art. Between 1927 and 1929, he launched yet another magazine, The Enemy, and in 1927 he also published Time and Western Man, which included critiques of such literary giants of the period as James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, and Ezra Pound. Both Pound and Joyce were friends of Lewis’, though his friendship with Joyce at least had not prevented Lewis from dismissing Ulysses in Time and Western Man as “diarrhoea.” Joyce, in turn, based the naysaying Ondt from his retelling of the Aesop fable “The Ant and the Grasshopper” in Finnegans Wake on Lewis.

The 1930s & 40s: Lewis Returns to Visual Art

Lewis, however, did not abandon his critical attacks on his fellow writers upon the dawning of a new decade. In 1930, he published The Apes of God, which included a chapter in which he lampooned the Sitwell family. This was part of a wider attack on the metropolitan literati of the time: following his split from the Omega Workshops, there was no love lost between Lewis and the Bloomsbury writer Virginia Woolf, for example. Lewis’ forthright, often gratuitous, attacks on other writers, however, naturally did little for his own standing within the London literary scene.

Though he went on to publish more literary works during the 1930s – including One Way Song, a book of poems, in 1933 and The Revenge for Love (1937), a novel set in the lead-up to the Spanish Civil War that was heavily critical of Communism in Spain – the 1930s and 40s marked a return to the visual arts after a long period of concentrated writing for Lewis. He is regarded as one of the great portrait artists of his generation, producing paintings of T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, and Edith Sitwell, among others. When his 1938 portrait of Eliot was rejected by the Royal Academy for their annual exhibition, renowned portrait artist Augustus John resigned by way of protest.

One of Lewis’ most famous paintings, The Surrender at Barcelona, dates from this period and was included in an exhibition at Leicester Galleries in 1937. Somewhat unconvincingly, perhaps, Lewis denied any connection between the painting and his novel The Revenge for Love, which was published that same year. Lewis claimed that he was painting a fourteenth-century scene, updated to suit modern artistic style and practices, rather than commenting on the Spanish Civil War itself. Two years later, in 1939, Barcelona’s then-Republican stronghold fell to Franco’s fascist regime.

Lewis, however, was not only critical of Spanish Communism; he was, in fact, an ideological supporter of Franco. Moreover, he wrote the first pro-Hitler book published in English in 1931. In Hitler, Lewis portrayed the leader of Germany’s Nazi party as an unassuming man of peace in a country beset by communist mob violence. He did later revise some of these views following a trip to Berlin in 1937, and in 1939, he wrote The Hitler Cult (in which he publicly disavowed his former views on Hitler) and The Jews: Are They Human?, which (deliberately offensive title aside) was an attack on antisemitism. However, Lewis was ideologically opposed to democracy, and so there is reason to suspect (as Phil Baker does) that the books published by Lewis in 1939 “were part of a damage-limitation exercise” meant to help rehabilitate his public image.

The 1950s: Lewis’ Final Years

While the 1930s and 40s had seen Lewis return to painting as his primary mode of creative expression, his artistic career came to an end in 1951. As a result of a pituitary tumor pressing down on his optic nerve, Lewis was totally blind by 1951. He then turned again to writing, and by his death in 1957, he had written forty books.

To say that Wyndham Lewis was the arch-contrarian of modernism is an understatement. Described by W. H. Auden as “that lonely old volcano on the Right,” Lewis’ belligerence and hostility towards many of his fellow artists and writers turned into something much darker as the twentieth century witnessed the rise of fascism. Yet Lewis was, of course, not alone in his opinions: T. S. Eliot held deeply antisemitic views and praised the Daily Mail newspaper for its pro-Mussolini stance, while his poetic mentor and Lewis’ friend Ezra Pound actively collaborated with Mussolini and supported Hitler. As with these and other such controversial creatives, each of us individually must choose whether we can separate the artist from their art without overlooking their deeply problematic views.