It is an icy cold night in Vermont, USA. A farmer builds a fire in his field. He and his men take turns stoking the flames, fighting off the bitter cold to save his crop from freezing. Although it sounds like a scene from the dead of winter, it took place in the summer of 1816. That year, large areas of the world suffered from drought and famine as global temperatures plummeted in what became known as “The Year Without a Summer.” According to local historical accounts, conditions were so harsh that our Vermont farmer was the only farmer to harvest any corn in the region that year.

Through interviews with experts Professor Gillen D’Arcy Wood, Professor of Environmental Humanities and English at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and Professor Clive Oppenheimer, Professor of Volcanology at the University of Cambridge, we discover what happened in 1816 and whether it could happen again.

What Caused the Unusually Cold Weather?

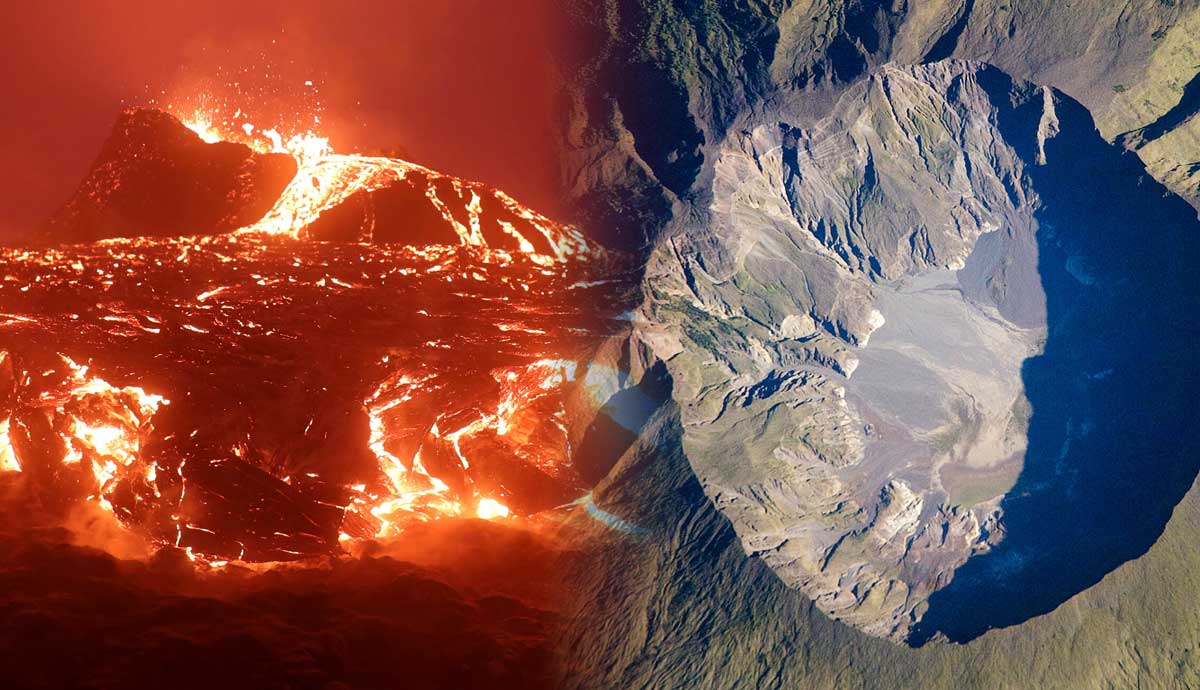

Experts believe that “The Year Without a Summer” was caused by a volcanic winter event following the eruption of Mount Tambora in April the year before.

The explosion on the island of Sumbawa, in what was then the Dutch East Indies and is now Indonesia, was the most destructive volcanic eruption in recorded human history. It was about ten times bigger than the 1991 eruption of Pinatubo in the Philippines.

It is estimated that about 10,000 people on the island were killed, while many more died in the years that followed due to the gas, dust, and rocks that were spewed up into the atmosphere.

A layer of sulfate aerosols, which are tiny dust particles, traveled around Earth high up in the stratosphere, reflecting some of the sun’s rays back into space. This led to significant cooling of the Earth’s surface, dropping Northern Hemisphere temperatures by up to 0.8°C.

Professor Gillen D’Arcy Wood, Professor of Environmental Humanities and English at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, told The Collector that the stratospheric aerosols first circulated the globe at the equator before drifting towards the poles and eventually enveloping Earth in a veil of dust.

“There are so many reports from those years, 1816 and 1817, that the sunlight was sort of dim. As if someone had turned the dimmer light down on the planet,” he said. “And then there were all these crazy weather anomalies.”

Impact Around the Globe

The unusually cold weather and heavy rains caused widespread crop failure in Europe, which was struggling to recover from the Napoleonic Wars. The continent suffered its worst famine of the century, and hungry people in the cities took to rioting. Between 1816 and 1819, major typhus epidemics also occurred in parts of Europe, including Ireland, Italy, Switzerland, and Scotland, precipitated by the famine and killing thousands.

North America experienced a persistent “dry fog” that dimmed sunlight, along with severe spring and summer frosts that damaged crops. The crop failures prompted many settlers in New England to migrate westward in search of better-growing conditions.

In Asia, the disruption of the monsoon season caused catastrophic floods in China’s Yangtze Valley, and the Yunnan region suffered a deadly famine. One poet described a mother choosing to drown her child rather than watch it starve. The delayed monsoon season also affected India, causing late torrential rains. This aggravated the spread of cholera from the Bengal region, which was hit by abnormal cold and snow.

Cholera Pandemic

In his book “Tambora: The Eruption That Changed the World,” Professor Wood examined the link between the extreme weather in India and the emergence of cholera as a global pandemic.

“There’s an argument for the grand historical impacts of Tambora, and at the top of the list would be cholera,” he said.

This extreme weather event created by the Tambora Volcano precipitated a change in the viral makeup of the cholera microbe, which essentially caused global cholera.

“Cholera had been endemic to Bengal for centuries,” he added. “But post-1815 it was exported and went on to become a global pandemic with a death toll in the millions.”

Professor Wood is an expert on this period, having trained as a specialist in 19th-century literary history. But it was not until he attended a lecture on climate that he became aware of Tambora and how the eruption influenced so much of that age.

“Here I was, this supposed scholar of the period, and right in the heart of it was an earth-changing epochal ecological event of which I knew nothing at all,” he said. “Out of that lecture, I decided it was a sign from the universe that I needed to investigate this.”

He described researching it as a once-in-a-lifetime project because it was “so important yet so understudied.”

“It was the answer to my own existential problem at the time, which was how to link my growing interest in the issue of climate change with my own work. Here was the topic which united them,” he said.

His book, published in 2014, was the first to present a comprehensive investigation into the disaster’s effects on global society. He used the creation of the novel Frankenstein, one of the most well-known works of English literature, as a kind of frame for his book.

In 1816, Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein, was spending her summer in Switzerland to visit Lord Byron. Her trip was heavily impacted by the unusual weather conditions caused by Tambora’s eruption.

“Shelley and the rest of them probably imagined having nice picnics in the Alps in the summer sun, but they were kept indoors by these terrible storms and cold weather,” Professor Wood said.

With the group stuck inside, they decided to have a competition to see who could write the best ghost story.

“And out of that, from her imagination, she was only 18 or 19 years old, she comes up with Frankenstein, which may sound peripheral, but I think it shows that from an extreme weather event someone produces an entirely novel and enduring cultural icon.”

“Without Tambora, we wouldn’t have Frankenstein. Imagine that world,” he added.

Could It Happen Again?

There are more than 1,500 active volcanoes on Earth, and around 50–70 erupt every year. However, according to the British Geological Survey, most volcanoes are not well monitored or even monitored at all.

Volcanic eruptions can range from the emission of gases and quiet eruptions of lava flows that can be safely observed to powerful eruptions that can blow apart mountains.

They are measured on a scale called the Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI), which categorizes eruptions based on magnitude and intensity on a scale from 0 as the lowest to 8 as the highest.

The eruption of Mount Tambora was the most recently confirmed VEI-7 eruption.

“Since Tambora, it’s been relatively quiet. The bottom line is we are certainly due another major eruption,” Professor Wood said.

Professor Clive Oppenheimer, Professor of Volcanology at the University of Cambridge, said the next big eruption will likely be from a volcano that is not being monitored.

“Most eruptions are relatively mild. As you crank up the scale, they become rarer and rarer events, and the things I think we learn from, say, the last 40-50 years is that the biggest eruptions often take us by surprise because they’re volcanoes that we weren’t looking at,” he said.

“A great example of that is the 1991 eruption of Pinatubo in the Philippines. This was completely off the scientific radar. And it produced the largest eruption, now in over a century, and it did have a detectable impact on global climate.”

Scientists observed a maximum global cooling of about 0.5°C in the year after the Pinatubo eruption, and the cooling effects lasted about three years.

Are We Prepared for Another Event?

Prof Oppenheimer said that an eruption on the scale of Tambora today would cause devastation across a zone of about 10 to 20 kilometers around the volcano, while ash fallout would affect a much wider area. He added that the immediate impacts on people will depend on where the volcano is located.

“If it’s in Antarctica, it’s going to have a very minimal impact compared with if it is in Indonesia,” he said.

The first thing he and other scientists would look for after such an eruption, besides the immediate impact at ground zero, would be the level of sulfur released into the atmosphere, as that is what will impact global climate.

“The size of the eruption does not necessarily scale with how much sulfur is released. Certain magmas have a lot more sulfur than others, so even if we get a very big bang, it doesn’t mean necessarily that we end up with a lot of climate change,” he said.

“If it was high sulfur, like a Tambora event, we would be pretty confident to expect a strong climate change. Not everywhere will be cooler in the summer after the eruption, but on average there will be a quite noticeable, measurable degree of cooling.”

Professor Oppenheimer said that an eruption on the scale of Tambora would likely be preceded by months of seismic activity, so there would be some warning.

He added that there is growing interest in whether the world is prepared for the next large volcanic event.

“To some extent, we’re prepared for various kinds of shocks that might have very different causes, but perhaps similar kinds of impacts. We have aid systems; we have international organizations responding to crises,” he said.

“In terms of preparedness, I think generic preparedness for global food crises will be relevant to the effects of the next Tambora.”